There are conflicting data on the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in coronary artery ectasia (CAE). It is unclear whether CAE is associated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT). We therefore investigated major cardiovascular risk factors, serum GGT and hs-CRP levels in a large population of patients with CAE.

MethodsA total of 167 patients with isolated CAE and 150 controls with normal coronary arteries were selected from 10505 patients undergoing coronary angiography. Serum GGT and hs-CRP levels were evaluated in addition to cardiovascular risk factors including family history, obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

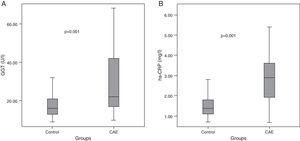

ResultsHypertension and obesity were slightly more prevalent in CAE patients than in controls, whereas diabetes was slightly less frequent in CAE patients. Other risk factors were similar. Serum GGT (22 [17–42] vs. 16 [13–21] U/l, p=0.001) and hs-CRP (2.9 [1.9–3.6] vs. 1.4 [1.1–1.8] mg/l, p=0.001) levels were higher in CAE patients than in controls. The presence of CAE was independently associated with diabetes (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20–0.95, p=0.04), obesity (OR: 2.84, 95% CI: 1.07–7.56, p=0.04), GGT (OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.12, p=0.001) and hs-CRP levels (OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 2.1–4.6, p=0.001). In addition, GGT and hs-CRP levels were higher in diffuse and multivessel ectasia subgroups than focal and single-vessel ectasia subgroups (each p<0.05).

ConclusionsOur findings show that CAE can be independently and positively associated with obesity, GGT and hs-CRP levels, but inversely with diabetes. Moreover, its severity may be related to GGT and hs-CRP levels.

Existem dados contraditórios relativamente à prevalência dos fatores de risco cardiovascular na ectasia da artéria coronária (EAC). Não é claro se a EAC possa estar associada à proteína C reativa de alta-sensibilidade (PCR-as) e à gama glutamiltransferase (gama-GT). Assim examinámos fatores de risco cardiovascular major, a gama-GT sérica e os níveis de PCR-as numa população mais alargada de doentes com EAC.

MétodosForam selecionados um total de 167 doentes com EAC isolada e 150 casos-controlo com artérias coronárias normais dos 10 505 doentes submetidos a angiografia coronária. A gama-GT sérica e os níveis de PCR-as foram avaliados para além dos fatores de risco cardiovascular incluindo a história familiar, obesidade, tabagismo, diabetes, hipertensão e hiperlipidemia.

ResultadosA hipertensão e a obesidade foram ligeiramente mais prevalentes nos doentes com EAC do que nos casos-controlo enquanto a diabetes foi menos frequente nos doentes com EAC. Os outros fatores de risco foram semelhantes. Os níveis de gama-GT sérica [22 (17-42) versus 16 (13-21) U/L, p =0,001] e de PCR-as [2,9 (1,9-3,6) versus 1,4 (1,1-1,8) mg/L, p =0,001] foram superiores nos doentes com EAC do que nos casos-controlo. A presença de EAC foi independentemente associada à diabetes (OR: 0,44, IC 95%: 0,20-0,95, p =0,04), obesidade (OR: 2,84, IC 95%: 1,07-7,56, p =0,04), gama-GT (OR:1,08, IC 95%: 1,03-1,12, p =0,001) e níveis de PCR-as (OR:3,1, IC 95%: 2,1-4,6, p =0,001). Além disso, os níveis de GGT e de PCR-as foram superiores nos subgrupos de ectasia difusa e mutivasos do que nos subgrupos de ectasia focal e de um vaso (cada p < 0,05).

ConclusãoAs nossas conclusões mostram que a EAC pode ser certamente associada à obesidade, aos níveis de gama-GT e de PCR-as, mas de modo inverso à diabetes. Além disso a sua gravidade pode estar associada aos níveis de gama-GT e de PCR-as.

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is characterized by an abnormal dilatation of the coronary arteries.1–3 More than half of cases of CAE are due to atherosclerosis, and it has thus been considered a variant of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD).1–3

It has been shown that inflammation is one of the causes of atherosclerosis.4 Similarly, previous studies have shown a link between C-reactive protein (CRP) and CAE.5,6 However, these studies were relatively small. On the other hand, there is a variety of data on the association of major risk factors for atherosclerosis with CAE.2,3,7–11

Gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) catalyzes glutathione, a major non-protein antioxidant in the cell.12 It plays a role in oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.13,14 Epidemiologic studies have reported that serum GGT level has predictive value for cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population.15–17

There have been two studies evaluating GGT levels in CAE patients. They showed that GGT levels were increased in patients with CAE,18,19 but these studies were small. Therefore, we aimed to investigate serum GGT and CRP levels in addition to major risk factors for atherosclerosis in a larger population of patients with isolated CAE.

MethodsPatientsBetween January 2007 and December 2012, 427 (4.1%) patients with CAE were selected from 10505 patients who underwent elective diagnostic coronary angiography in our center. After application of the exclusion criteria, the remaining 167 (1.6%) isolated CAE patients were designated the CAE group. During the same period, 150 age- and gender-matched controls with normal coronary arteries were consecutively selected. The indication for coronary angiography was the presence of typical angina pectoris or significant myocardial ischemia in noninvasive stress tests.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: acute coronary syndromes, history of alcohol consumption, high alanine and/or aspartate transaminase levels, presence of concomitant stenotic lesion (>25% stenosis), significant left ventricular hypertrophy (septal thickness ≥13 mm), hematologic disorders, acute or chronic infectious disease, hepatitis or previously known inflammatory/autoimmune disorders, renal dysfunction (serum creatinine ≥177 mmol/l), documented cancer, use of steroids, and significant valvular heart disease (moderate to severe for stenotic lesions or grade ≥2 for valvular regurgitation).

A detailed medical history and history of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension and smoking were obtained from the study population. For each patient, body mass index (BMI) was calculated by the formula of weight (kg) divided by height (m)2. BMI was categorized as normal (≤25 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2) or obesity (>30 kg/m2). Hypertension was considered to be present if systolic blood pressure was ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure was ≥90 mmHg or both, or if the individual was taking antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as the use of antidiabetic therapy or a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥7 mmol/l (≥126 mg/dl) in at least two measurements. Family history of CAD was diagnosed if patients had a first-degree male relative <55 years of age or female relative <65 years of age with CAD. Patients who smoked before hospitalization were classified as smokers. Hyperlipidemia was defined as LDL cholesterol ≥3.4 mmol/l (≥130 mg/dl), triglycerides ≥2.26 mmol/l (≥200 mg/dl) or use of lipid-lowering drugs.

All patients gave their informed consent for participation in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee.

Blood sampling and assaysBlood samples were drawn after a fasting period of 12 hours. Serum glucose, creatinine and lipid profile were determined by standard methods. Whole blood counts were made in a blood sample collected in dipotassium EDTA tubes with an automatic blood counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA). Serum GGT levels were measured by the enzymatic calorimetric method using commercially available test kits with an AU640 auto-analyzer (Olympus, Japan). Normal values were defined as 0–50 U/l in our laboratory. In addition, other biochemical tests were performed using original kits with the Olympus autoanalyzer. Serum hs-CRP was measured by nephelometry using commercially available kits in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Beckman Coulter Array 360, Brea, CA, USA).

Angiographic evaluationUsing the Judkins technique, coronary angiography was performed with contrast agents without intracoronary nitroglycerin. Arteriograms were obtained in both right and left anterior oblique projection with caudal and cranial angulation for the left and right coronary system. Additional views were also obtained in patients with inadequate visualization. Images were recorded in digital format and stored for later analysis. Right anterior oblique view was used to evaluate ectasia for the left coronary system and left anterior oblique view for the right coronary artery. Evaluations were performed visually by two experienced angiographers blinded to each other's findings. Vessel diameter was calculated quantitatively in the event of disagreement concerning CAE. Each major coronary artery was subdivided into proximal, mid, and distal segments.

Coronary ectasia was defined as dilation exceeding 1.5 times the normal diameter of normal adjacent segments.1–3 If no normal adjacent segment could be identified, the mean diameter of the corresponding segment in the control group was taken as the normal value. If the coronary arteries had a normal appearance or no atherosclerotic plaques with ≥25% stenosis, they were regarded as normal. Patients with concomitant obstructive and ectatic lesions were not included in the study. CAE was defined as focal when involving one segment and as diffuse when involving two or more segments in a major coronary artery, and as severe when diffuse (≥2 segments) in ≥2 vessels.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR] of the 25th–75th percentiles of GGT and hs-CRP levels) and categorical variables as number (%). Comparisons between the groups were performed with the Student's t test, the Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Gender-specific GGT tertiles were calculated in both groups, with GGT cut points of 18 and 24 U/l in men and 15 and 23 U/l in women delineating low, mid and top tertiles. Similarly, hs-CRP was categorized into low, mid and top tertiles (cut points of 1.53 and 2.56 mg/l). After univariate analyses had been performed for CAE, binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent variables associated with the presence of CAE. Confounders which had significance at the p≤0.15 level were entered into the regression analysis. They were hypertension, diabetes, obesity, triglycerides, uric acid, GGT, hs-CRP and platelet count. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The correlation between GGT and CRP levels was evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

ResultsThe demographic and clinical characteristics of the CAE and control groups are presented in Table 1. Hypertension and obesity were slightly more prevalent in CAE patients compared with controls, whereas the prevalence of diabetes was slightly lower. Other parameters were comparable in the two groups.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | CAE group (n=167) | Control group (n=150) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.7±8.2 | 59.7±7.6 | 0.38 |

| Male/female | 102/65 | 84/66 | 0.42 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1±2.7 | 26.9±2.6 | 0.50 |

| Smoking | 64 (38%) | 70 (47%) | 0.16 |

| Hypertension | 124 (74%) | 96 (64%) | 0.052 |

| Diabetes | 31 (19%) | 41 (27%) | 0.08 |

| Family history of CAD | 30 (18%) | 22 (15%) | 0.45 |

| Dyslipidemia | 58 (35%) | 46 (31%) | 0.47 |

| Obesity | 27 (16%) | 13 (9%) | 0.06 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 128±16 | 127±14 | 0.55 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77±9 | 76±8 | 0.30 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 162 (97%) | 148 (99%) | 0.45 |

| Beta-blockers | 142 (85%) | 118 (79%) | 0.17 |

| Statins | 50 (30%) | 39 (26%) | 0.51 |

| ACEIs or ARBs | 80 (48%) | 39 (56%) | 0.18 |

| Calcium antagonists | 23 (14%) | 26 (17%) | 0.44 |

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CAE: coronary artery ectasia; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Coronary ectasia was located most frequently in the left anterior descending artery (62%), followed by the right coronary artery (59%) and circumflex artery (29%). Diffuse ectasia was seen in 91 patients (55%) and multivessel ectasia in 67 (40%).

Laboratory variables of the study groups are shown in Table 2. Triglyceride level and platelet count were higher in the CAE group than in the control group. Similarly, CAE patients had slightly higher uric acid levels (329.2±75.6 vs. 311.7±72.7 μmol/l, p=0.06). Other parameters were similar in both groups.

Laboratory parameters of the study population.

| CAE group (n=167) | Control group (n=150) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 6.10±1.51 | 6.28±2.66 | 0.45 |

| AST (U/l) | 22.6±7.3 | 23.6±8.7 | 0.27 |

| ALT (U/l) | 20.2±8.8 | 21.1±9.7 | 0.39 |

| GGT (U/l)a | 22 (17–42) | 16 (13–21) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l)a | 2.9 (1.9–3.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mmol/l) | 90.71±17.05 | 94.18±20.73 | 0.80 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.78±0.89 | 4.81±1.02 | 0.77 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l)a | 1.63 (1.34–2.24) | 1.51 (1.13–2.25) | 0.02 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.12±0.17 | 1.10±0.22 | 0.36 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 2.68±0.70 | 2.77±0.67 | 0.24 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 329.2±75.6 | 311.6±72.7 | 0.06 |

| Fibrinogen (μmol/l) | 10.23±1.79 | 9.92±1.77 | 0.13 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.4±1.3 | 13.3±1.4 | 0.51 |

| WBC (×109/l) | 7.88±1.9 | 8.11±2.2 | 0.32 |

| Platelet count (×109/l)a | 248 (190–286) | 194 (170–216) | 0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 63±5 | 62±6 | 0.34 |

ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; GGT: gamma glutamyltransferase; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC: white blood count.

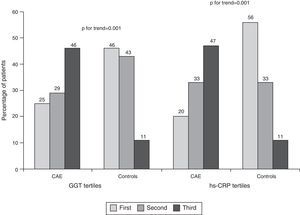

Median GGT level was higher in CAE patients than in controls (22 [IQR: 17–42] vs. 16 [IQR: 13–21] U/l, p=0.001, Table 2, Figure 1A). Similarly, hs-CRP levels were higher in CAE patients than in controls (2.9 [IQR: 1.9–3.6] vs. 1.4 [IQR: 1.1–1.8] mg/l, p=0.001, Figure 1B). The percentages of patients in the top tertile of GGT and hs-CRP were higher in CAE patients than in controls (p for each trend=0.001, Figure 2).

In logistic regression analysis, the presence of CAE was independently and positively associated with GGT levels (OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.12, p=0.001), hs-CRP levels (OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 2.10–4.59, p=0.001) and obesity (OR: 2.84, 95% CI: 1.07–7.56, p=0.038), but negatively with diabetes (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20–0.95, p=0.036).

In addition, GGT and hs-CRP levels were significantly higher in diffuse and multivessel ectasia subgroups than in focal and single-vessel ectasia subgroups (Table 3). There was a moderate correlation between GGT and hs-CRP levels (r=0.50, p=0.001).

Serum gamma glutamyltransferase and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in subgroups of patients with coronary artery ectasia.

| Focal ectasia (n=76) | Diffuse ectasia (n=91) | p | Single-vessel (n=100) | Multivessel (n=67) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGT (U/l) | 16 (13–20) | 42 (25–47) | 0.001 | 19 (15–22) | 45 (40–48) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) | 3.1 (2.1–3.7) | 0.01 | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 3.2 (2.7–3.9) | 0.001 |

Values are median (interquartile range). p values were calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test. GGT: gamma glutamyltransferase, hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

In this study, obesity and hypertension were slightly more prevalent but diabetes less prevalent in CAE patients than in controls. Similarly, serum GGT and hs-CRP levels were higher in patients with CAE. The presence of CAE was positively associated with obesity and GGT and hs-CRP levels but inversely with diabetes. Also, the severity of CAE was linked with GGT and hs-CRP levels.

The prevalence of CAE varies from 1% to 5% in angiographic series.1–3 Although CAE is largely attributed to atherosclerosis, its causative and pathologic mechanisms are not clearly understood.1–3 It may appear a relatively innocent clinical entity; however, it can cause cardiac events such as stable or unstable angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and cardiac death.7,9,20

Cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery ectasiaPrevious small studies have reported different frequencies of major risk factors for atherosclerosis in isolated CAE patients.2,3,7–11 In our study, there was a predominance of male gender (58%) in CAE patients, as in previous studies.2,8,11,18,21 The proportion reaches 85% in some studies.7,9

Among risk factors, hypertension and obesity were slightly more prevalent in isolated CAE patients in the present study, whereas the rate of diabetes was lower in CAE patients. Other factors were at similar percentages. Only one study has shown a higher frequency of hypertension in CAE patients,11 in contrast to other studies.2,3,7–10,18,19 Similarly, hyperlipidemia has been reported to be more common in CAE patients in one study9 but not in others.2,3,7,8,10,11,18,19 Both high8 and low7,9 prevalences of smoking have also been documented in patients with CAE. We consider that these conflicting results may be mainly due to the selection of the control group from patients undergoing coronary angiography, and the small size of the studies. We constituted the control group from patients with normal coronary arteries, whereas some studies selected patients with CAD as the control group.7,9

Interestingly, previous studies8,10 reported an inverse association between CAE and diabetes, as in our study, in which diabetes independently decreased the likelihood of CAE (OR: 0.44). However, this inverse association was not seen in several other studies.3,4,7,9,11,18 There are two potential explanations for this association: in diabetic patients, compared with non-diabetic patients, negative arterial remodeling is seen more frequently in the coronary arteries during the progression of atherosclerotic plaques22; and consequently obstructive CAD can be found more commonly in diabetic patients.23

We found that obesity independently increased the likelihood of CAE (OR: 2.84, p=0.04). Such an association was not present in previous studies.2,3,7–11,18,21 We think that this finding may be the result of compensatory enlargement due to increased body weight, because we did not routinely measure the diameters of the ectatic vessels and did not index them to body surface area.

Gamma glutamyltransferase, inflammation and coronary artery ectasiaIn humans, GGT is responsible for extracellular catabolism of glutathione, an antioxidant.12 There is evidence that GGT triggers oxidative stress within atherosclerotic plaque and promotes the atherosclerotic process by means of LDL oxidation.12–14 This finding has been supported by large epidemiologic studies15,16 in which GGT level is independently associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality. Furthermore, it is an independent predictor of fatal and non-fatal cardiac events in patients with documented CAD.22

Two recent studies have reported that GGT levels are increased in patients with isolated CAE compared to controls with normal coronary arteries, but are not associated with the severity of CAE.18,19 Their sample size was small, including only 88 and 45 CAE patients. In our larger study, CAE patients had a higher level of GGT compared with controls. Moreover, GGT was independently associated with the presence of CAE as well as with the severity of CAE. We think that GGT may have a prognostic value for CAE, as also reported for atherosclerotic CAD.24

Inflammation plays a key role in the atherosclerotic process and CRP can predict future cardiovascular events in men and women at risk.4 hs-CRP has been documented to be elevated in patients with CAE in some studies5,6 but not in others.25,26 However, these studies had small patient populations. In the present study, hs-CRP levels were higher in CAE patients than controls, and independently associated with the presence of CAE.

Previous studies showed an association of GGT with CRP.13,27,28 GGT can act as a proinflammatory protein in atherogenesis27 and is associated with atherosclerotic risk factors including obesity, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, hypertension and diabetes.16,17,28 There was a moderate link between GGT and hs-CRP in our study. This evidence suggests that GGT and CRP may reflect chronic occult inflammation in CAE patients.

In addition, some small studies reported similar platelet counts in CAE and control groups,29–31 but in contrast, one large study reported significantly lower platelet counts in CAE patients than in controls.32 Similarly, in our larger study, platelet count was lower in the CAE group. We consider that these conflicting results may be mainly due to the small size of the studies.

LimitationsOur study has some limitations. Firstly, a major limitation is that we did not make prognostic assessments based on GGT levels, because of the small number of major cardiac events: two myocardial infarctions and three presentations with recurrent angina. Secondly, the prevalence of obesity was slightly higher in CAE patients, although mean BMI was similar in the two groups. Hepatic steatosis secondary to obesity may have contributed to higher GGT levels in CAE patients, but we did not evaluate this in each patient. Finally, our findings reflect the situation of patients with chest pain undergoing coronary angiography, but not that of the general population.

ConclusionOur findings show that the presence of CAE can be independently and positively associated with serum GGT and hs-CRP levels but negatively with diabetes. GGT and hs-CRP may also reflect the severity of CAE. Hence, their measurement may be useful in the evaluation of patients with CAE, as documented in patients with CAD. However, these findings should be supported by further studies.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.