The study published by Baptista et al.1 sought to assess the quality of antithrombotic therapy in a group of 996 patients with diabetes prior to coronary percutaneous intervention, searching for how guidelines are being applied in a real-world setting.

As expected, this population shows a clinically high risk profile in terms of ischemic/thrombotic risk. All patients had diabetes, approximately one third had clinical overt coronary artery disease (CAD) at admission and more than 50% were managed in the setting of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The results showed that 99.9% of patients without concomitant anticoagulation were discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and 84.5% of patients also treated with anticoagulants. This was a remarkable global result.

Only half of patients were discharged on a potent antiplatelet drug (ticagrelor or prasugrel), and the proportion was much higher in patients with ACS compared to chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) (74.7% vs. 16.1%; p<0.001), once again as expected.

The planned duration of DAPT was as per the guidelines: 12 months for 93.6% of ACS patients; six months for 55.2% patients with CCS, and 12 months for 44.4% patients with CCS. Shorter duration of DAPT was planned for very few patients: <6 months in CCS patients in 6.5% and <12 months in ACS patients in 2.5%.

I will briefly review some of the concepts related to the population of patients with diabetes and CAD and discuss the antiplatelet therapy regimen based on more recent evidence.

Diabetes and ischemic heart diseaseThe prevalence of ischemic heart disease (IHD) in patients with diabetes is very high, as several registries showed included in Portugal. According to Cardoso et al.2 in a group of patients with diabetes for 17.4 years, followed at a large university hospital, overt IHD was present in 54% of them.

In a primary care setting, also in Portugal, a recent publication by Alão et al.3 showed there were microvascular complications in 38.1% and macrovascular complications in 19.6% in a group of patients who had diabetes for more than 10 years. Patients with diabetes have specific biological, metabolic and anatomic characteristics responsible for a worse prognosis.4

Other evidence shows that in patients with diabetes there are characteristic platelet abnormalities, as well as a reduced response to antiplatelet medications,5 making patients with diabetes more susceptible to the thrombotic phenomenon.

The role of antiplatelet therapy is unquestionable in patients with IHD in its multiple forms, particularly after ACS and after revascularization. Unfortunately, its role in patients with diabetes has been poorly studied, so evidence has been built based on subgroup analyses in large, randomized trials designed to study the various drugs.6 Thus, patients with diabetes are treated with regimens validated in studies including only variable proportions of these patients.

Only one large randomized controlled trial has been conducted in patients with diabetes and CCS. The “Ticagrelor in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease and Diabetes” (THEMIS)7 enrolled 19 220 patients randomized into two groups: ticagrelor plus aspirin and placebo plus aspirin, for 39.9 months. The combination of ticagrelor plus aspirin showed a marginal benefit in reducing ischemic events (7.7% vs. 8.5%; hazard ratio, 0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.81–0.99; p=0.04), unfortunately neutralized by the increment in hemorrhagic risk. The rate of TIMI major was higher (2.2% vs. 1.0%; hazard ratio, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.82–2.94; p<0.001), as was the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage (0.7% vs. 0.5%; hazard ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.18–2.48; p=0.005).

In the THEMIS population, 11154 patients had a history of prior PCI, analyzed in the THEMIS-PCI.8 In this population, ticagrelor improved net clinical benefit: 519/5558 (9.3%) vs. 617/5596 (11.0%), HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.75–0.95, p=0.005, in contrast to patients without previous PCI where it did not, P interaction=0.012. Benefit was present irrespective of time from most recent PCI.

DAPT and PRECISE-DAPT scoresDespite the major benefit of DAPT, its efficacy should always be balanced according to the individual risk. Indeed, the intensity and duration of DAPT are regulated by European guidelines,9 and as a rule, DAPT should be used for 12 months after an ACS and for 6 months in patients without an acute setting. However, we treat patients with different conditions and clinical profiles, including those at high risk of bleeding. In this case, research helps us tailor therapy to the risk, not only selecting the best drug with the best dose but also selecting the best regimen.10

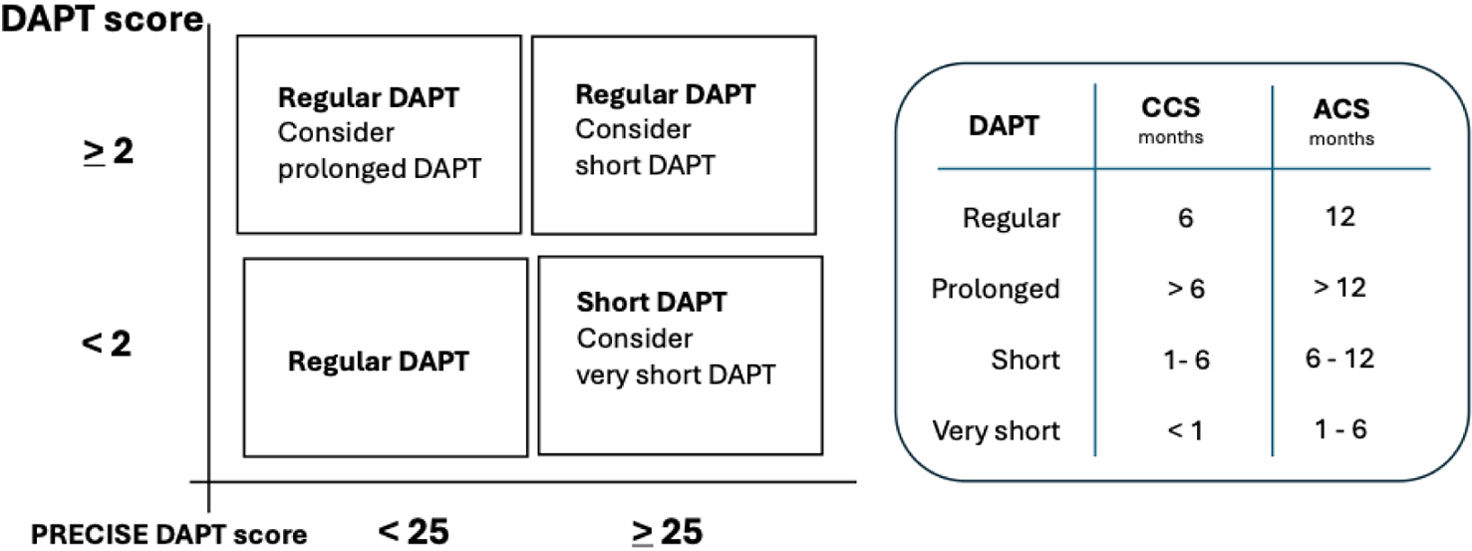

Two scores are particularly helpful for this purpose. The DAPT score11 to identify the individual thrombotic risk and the PRECISE-DAPT score12 to identify the hemorrhagic risk. The DAPT score ranges from − 2 to 10 points and the calculation of the score considers nine variables. The total score was determined by summation of all points of the nine predictive risk factors.

The PRECISE-DAPT scoring system ranges from 0 to 100 points, comprises five variables, i.e., age, creatinine clearance, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, and previous spontaneous bleeding. A score <25 shows that the patient has a low bleeding risk, standard or even prolonged duration of DAPT is recommended for patients with a DAPT score ≥2 due to higher ischemic risk. In contrast, short duration of DAPT (3–6 months) is recommended for patients with a PRECISE-DAPT score ≥25 due to the higher bleeding risks.

Both scores were introduced in our daily clinical practice in 2017 following the major update to guidelines13 focusing on antiplatelet therapy in patients with CAD; they were validated in large databases.14,15

In the publication by Baptista et al.1 individual follow-up data are not available, so we are not able to consider whether therapeutic decisions were correct or not. Nevertheless, the last five years of research extensively searched for alternative regimen to reduce the bleeding risk, preserving efficacy in terms of thrombotic risk.

The reduction of antithrombotic therapy, reducing antiplatelet potency, is a permanent challenge to clinicians. This goal can be achieved by replacing more potent drugs with older or less potent ones, or by reducing the duration of DAPT by evolving to monotherapy with a single antiplatelet agent.

Based on current knowledge and respecting the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, in patients at high risk of bleeding, antiplatelet therapy can be individualized as follows (Figure 1):

- •

The initial 30 days is the period of higher vulnerability of stents, in which thrombosis occurs more frequently. For this reason, a brief period of DAPT is always required.

- •

Compared to CCS thrombotic burden and thrombotic risk are greater in patients – post-ACS therefore more potent drugs (ticagrelor or prasugrel) are the best option.

- •

In patients with higher hemorrhagic risk, the shortening of DAPT is possible without any loss of benefit.

- •

Regardless of the individual risk in the initial months, any DAPT is better than no DAPT at all.

- •

De-escalation can be done by stopping aspirin and maintaining monotherapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor, preferably ticagrelor.

In the study by Baptista et al.,1 information was collected on drugs other than antithrombotics. Given the important role of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists in patients with diabetes, the authors investigated the prevalence of these drugs. The reported numbers show that prescriptions for these medications are surprisingly infrequent. Only 28% of patients were on SGLT2 inhibitors and 3% on GLP-1 agonists.

Nowadays, these two groups of drugs are recognized as highly efficacious and safe for treating diabetes. They encompass other large benefits in terms of prevention of cardiovascular diseases atherosclerosis related. SGLT2 inhibitors show large efficacy in patients after myocardial infarction16 and in patients after revascularization.17

In summary, registries are of paramount importance to better understand the reality and based on their results we can improve clinical practice.18 Regarding antithrombotic therapy in patients with IHD, we are moving into a new era. I hope that the upcoming guidelines will incorporate current knowledge based on intensive research, thus enabling more personalized medicine.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Editorial comment to the article published by Sergio Batista and colls. ARTHEMIS Registry.