When approaching a patient diagnosed with a ventricular tachyarrhythmia, a systematic search should be made for structural heart disease (the most common etiology being coronary disease), since this has important prognostic and therapeutic implications.

There is, however, a subgroup of patients who develop ventricular tachycardia in structurally normal hearts. This is known as idiopathic ventricular tachycardia and is estimated to account for up to 10% of cases of ventricular tachycardia.1

Two types of treatment are available for these patients: pharmacological and catheter ablation (or both simultaneously). Since these arrhythmias are focal, they are readily amenable to treatment with catheter ablation, with high success rates.2

Since the first description in the early 1980s of tachycardia originating in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) by Buxton et al. 3, our understanding of idiopathic ventricular tachycardias has increased greatly. Lerman et al. published a series of studies4–6 on the pathophysiological mechanisms involved, showing that most tachycardias originating in the RVOT are sensitive to adenosine, and that the most likely electrophysiological mechanisms are delayed afterpotentials and delayed afterdepolarizations mediated by catecholaminergic stimulation and triggered activity associated with intracellular calcium overload.7

Given the intracellular nature of their pathophysiology, it is logical that such tachycardias can be induced in the electrophysiological laboratory by administration of isoprenaline, aminophylline or atropine and rapid pacing, but rarely if ever by programmed ventricular stimulation.8

Outflow tract tachycardias, mainly located in the myocardium of the right and left ventricular outflow tracts, are a subgroup of idiopathic ventricular tachycardias. In 80-90% of them the right ventricular outflow tract is the origin of the arrhythmia.9

The prognosis is generally favorable, although physicians should be aware that some cases develop into left ventricular dysfunction (tachycardia-induced myopathy),10 and malignant variants have occasionally been described.11

An essential element of the diagnosis is careful analysis of the electrocardiogram (ECG), which can provide an accurate localization of the arrhythmia's origin in the left or right ventricular outflow tract (according to the morphology of the QRS complex in the right precordial leads) and even the segment of the tract.12

The impressive advances in the technology now at the disposal of cardiologists make a detailed knowledge of anatomy of prime importance.

Viewed from the frontal aspect of the chest, the right ventricle is the most anteriorly situated cardiac chamber because it is located immediately behind the sternum. The cavity of the right atrium is anterior, while the left atrium is the most posteriorly situated chamber. In contrast to the near conical shape of the left ventricle, the right ventricle is more triangular in shape.13

Both right and left ventricles can be described in terms of three component parts: inlet (inflow tract), apical trabecular, and outlet (outflow tract).14

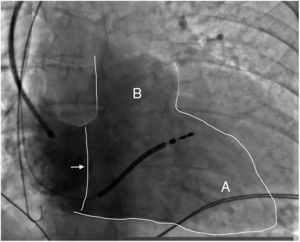

These three parts can be identified in Figure 1, in which one region (B) can be observed virtually separate from the rest of the right ventricle: the RVOT (infundibulum).

Fluoroscopic image of the right ventricle (outlined in white) in right anterior oblique view at 30° with contrast, showing the tricuspid valve (arrow), the right ventricular apex (A) and the right ventricular outflow tract (B). An active fixation cardioverter-defibrillator lead is also visible, with its tip in the upper-mid septal region (Silva Cunha P, Oliveira M).

This issue of the Journal includes a study by Parreira et al.,16 which, although based on a small patient population, is interesting and useful from a clinical standpoint. The authors studied 18 patients with more than 10 000 premature ventricular contractions (PVCs)/24 hours during Holter recording, probably originating from the RVOT, and analyzed the correlation between electrocardiographic findings and the results of electroanatomical voltage mapping during electrophysiological study.

Before the electrophysiological study, patients underwent a conventional ECG followed by a second ECG in which the frontal plane leads V1 and V2 were placed in the second intercostal space, in closer proximity to the RVOT as explained above, in order to obtain more precise data on its electrical activity.

In over a third of patients the second ECG showed ST-segment elevation that correlated with the presence of low voltage areas in the RVOT.

Several studies have shown that an ECG obtained in a higher position than normal (in the second or third intercostal space) helps detect right ventricular alterations, and may, for example, increase diagnostic sensitivity in cases of suspected Brugada syndrome.15

The study by Parreira et al. did not completely rule out structural heart disease, since not all patients underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to exclude the presence of regional myocardial fibrosis. Even so, the study is important for identifying regional pathological alterations on the ECG that were confirmed by the detection of low voltage areas on three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping in patients with apparently normal hearts.

This finding suggests that in many published cases of right ventricular tachycardias considered to be idiopathic, i.e. in apparently normal hearts, structural abnormalities do in fact exist at a very early stage, but are not identified because of a lack of sufficiently sensitive diagnostic instruments.

It should be noted that the presence of ST-segment changes and low voltage areas did not correlate with rates of acute ablation success or of recurrence.

It would have been interesting if the authors had addressed the question of whether there is a minimum anatomical area of low voltage that correlates with the ECG alterations, by presenting the total areas measured.

Despite these methodological limitations (plus the fact that two different mapping systems were used), we would encourage the authors to continue this line of investigation.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Cunha PS. Eletrocardiograma na era do mapeamento tridimensional. Qual o segredo da sua juventude?. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:93–95.