The authors present the results of the national cardiac electrophysiology registry of the Portuguese Association of Arrhythmology, Pacing and Electrophysiology (APAPE) and the Portuguese Institute of Cardiac Rhythm (IPRC) for 2017 and 2018.

MethodsThe registry is annual, voluntary, and observational. Data are collected retrospectively. Developments over the years and their implications are analyzed and discussed.

ResultsIn the 22 electrophysiology centers, 3407 ablations were performed in 2017 and 3653 ablations in 2018. Atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation was the most frequently performed procedure: 1017 ablations in 2017 and 1222 procedures in 2018. Of the patients undergoing AF ablation, 63% were male, 60% were between 50 and 69 years old and 74% had paroxysmal AF. Clinically relevant complications were reported in 0.8% of the procedures. In 2017, 216 ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) ablation procedures were performed in 15 centers. In 2018, 19 centers performed 249 TV/VF ablations. About 45% of VT/VF ablations were performed in patients with structural heart disease. Complications were reported in 3.2% of the procedures, including one death (0.2%).

ConclusionsThe national electrophysiology registry showed a sustained increase in the number of catheter ablations. In addition, procedural complexity increased and AF ablation assumed a dominant position among the procedures performed.

Apresentam-se os dados referentes ao Registo Nacional de Eletrofisiologia Cardíaca da Associação Portuguesa de Arritmologia, Pacing e Eletrofisiologia (APAPE) e Instituto Português do Ritmo Cardíaco (IPRC) para os anos de 2017 e 2018.

MétodosTrata-se de um registo anual, voluntário, observacional e retrospetivo. É analisada a evolução da atividade dos Centros de Eletrofisiologia tendo em conta o tipo de procedimentos realizados e são discutidas as potenciais implicações.

ResultadosNos 22 Centros de Eletrofisiologia em funcionamento foram realizadas 3407 ablações em 2017 e 3653 ablações em 2018. A ablação de fibrilhação auricular foi o procedimento mais frequente (1017 ablações em 2017 e 1222 em 2018). Dos doentes submetidos a ablação de fibrilhação auricular, 63% eram do sexo masculino, 60% apresentavam entre 50 e 69 anos de idade e 74% tinham arritmia paroxística. Foram reportadas complicações clinicamente relevantes em 0,8% dos procedimentos.

Em 2017, foram efetuadas 216 ablações de taquicardia ventricular ou fibrilhação ventricular (TV/FV) em 15 centros. Em 2018, 19 centros realizaram 249 ablações de TV/FV. Cerca de 45% das ablações de TV/FV foram efetuadas em doentes com cardiopatia estrutural. Foram reportadas complicações em 3,2% dos procedimentos, incluindo um óbito (0,2%).

ConclusãoA eletrofisiologia nacional mantém um crescimento no número de ablações por cateter. Além disso, verificou-se aumento na complexidade das ablações realizadas, assumido a ablação de fibrilhação auricular uma posição dominante entre os procedimentos efetuados.

The national cardiac electrophysiology registry of the Portuguese Association of Arrhythmology, Pacing and Electrophysiology (APAPE) and the Portuguese Institute of Cardiac Rhythm (IPRC) is a voluntary observational registry that includes all public and private centers that perform electrophysiological studies. It has functioned continuously since 19911 and can thus be used to analyze changes in activity in the field of electrophysiology in Portugal over the last two decades.2–11 Specifically, it shows developments in terms of number and size of active centers, physical, human and technological resources, and number and type of techniques used.

We present the results for the two years 2017 and 2018, electronic data for which were collected annually. In order to enable a more detailed characterization of the centers’ activity, the questionnaire used included three new sections: (1) characterization of the physical, human and technological resources used in each center; (2) detailed characterization of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation procedures in terms of gender, age, type of AF, ablation technique and clinically significant complications; and (3) detailed characterization of ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation procedures in terms of gender, age, etiology, mapping and ablation techniques, and complications.

Data from the registry are also included in the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) White Book, which describes the treatment of arrhythmias in countries in the European Society of Cardiology area.12–14 The results of the present study are discussed and compared to data from European Union (EU) Member States for 2016 published in the 10th edition of the EHRA White Book.14

MethodsThe National Registry on Cardiac Electrophysiology is based on data collected annually and retrospectively from electrophysiology centers operating in Portugal. The questionnaire used is available online and the coordinator of each center is responsible for providing the data, which are taken from the centers’ computer databases. The questionnaire consisted of four parts: (1) characterization of the center, describing its physical, human and technological resources; (2) characterization of the center’s activity, including number of diagnostic electrophysiological studies and of the different types of ablation performed; (3) characterization of AF ablation procedures, specifying distribution by age, gender, clinical classification of AF, type of procedure, ablation technique used and clinically relevant complications reported; and (4) characterization of VT ablation procedures, specifying distribution by gender, etiology of the underlying heart disease, mapping techniques (exclusively endocardial or including an epicardial approach), and clinically relevant complications reported.

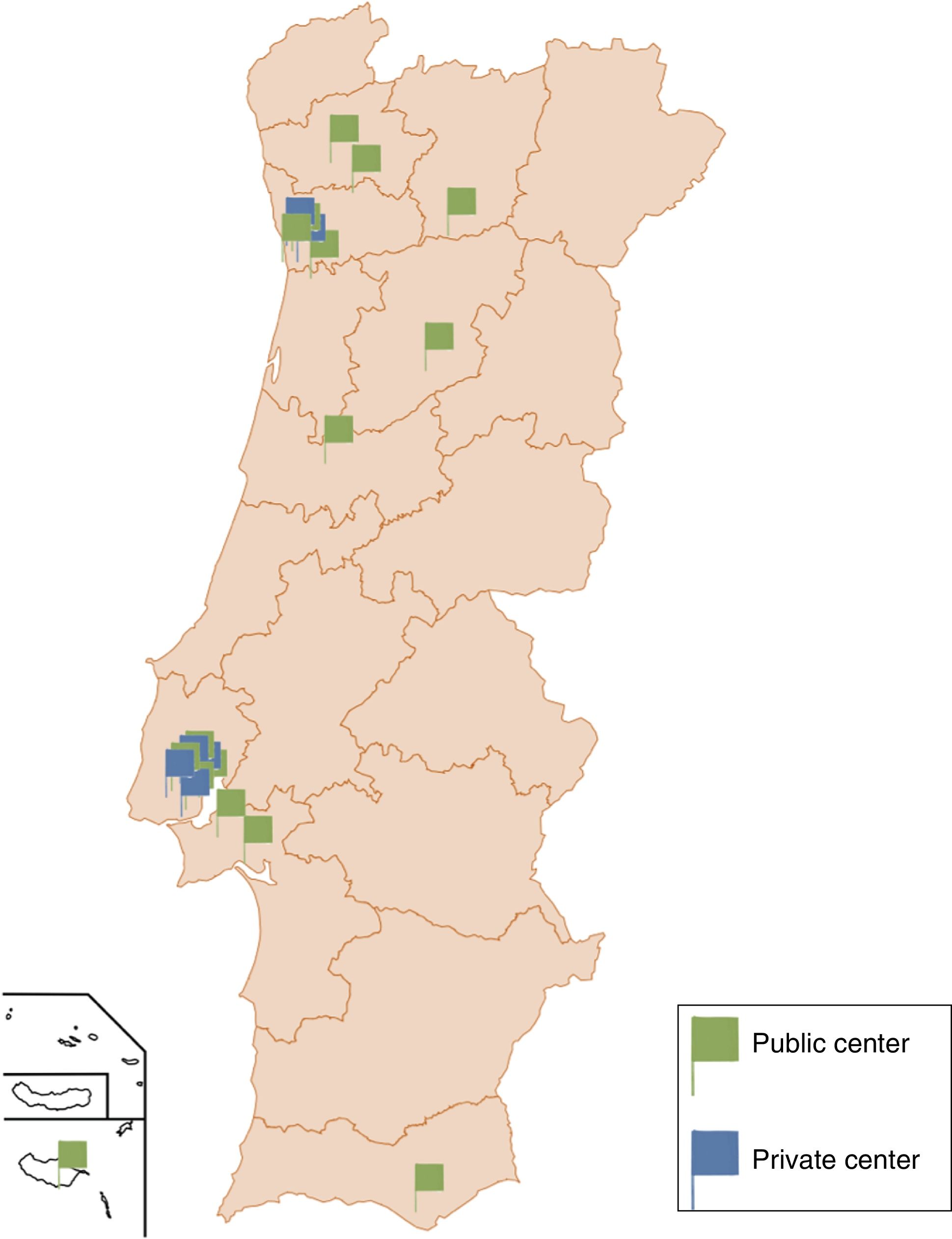

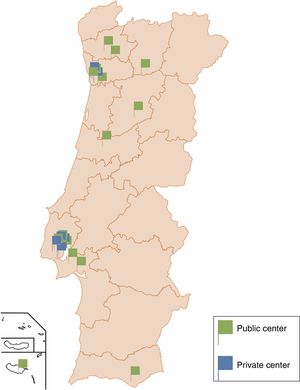

ResultsCharacterization of electrophysiology centersAll Portuguese centers responded to the survey in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, 22 electrophysiology centers were operating, of which 15 were in public hospitals (68%) and seven in private health institutions (32%). This represents a slight reduction in the overall number of active centers (compared to 25 in 2014) due to some private centers ceasing operation (there had been 11), while one more center opened in a public hospital (previously 14). In 2018, the number of centers remained unchanged, with one public center opening and one private center ceasing activity.

Sixteen of the country’s electrophysiology centers, including all of the private centers, were located in the greater Lisbon (n=11) and greater Porto (n=5) areas (Figure 1).

With regard to physical resources, in 2018 all centers were equipped with polygraphs (five centers had two polygraphs) and fluoroscopy systems (seven centers had two image intensifiers). Only one private center did not have a three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping system, while 12 centers (55%) had at least two such systems.

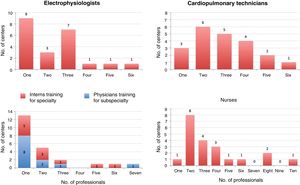

In terms of human resources, there were 33 electrophysiologists active in 2018, 18 of them also practicing in private institutions. The teams included at least two electrophysiologists in 13 centers (13%), two cardiopulmonary technicians in 18 centers (82%), and two nurses in 20 centers (91%). Human resources also included 15 physicians undergoing training for the subspecialty of cardiac electrophysiology. Eleven centers provided training for the internship in arrhythmology during training for the specialty of cardiology. Details of the human resources involved are presented in Figure 2.

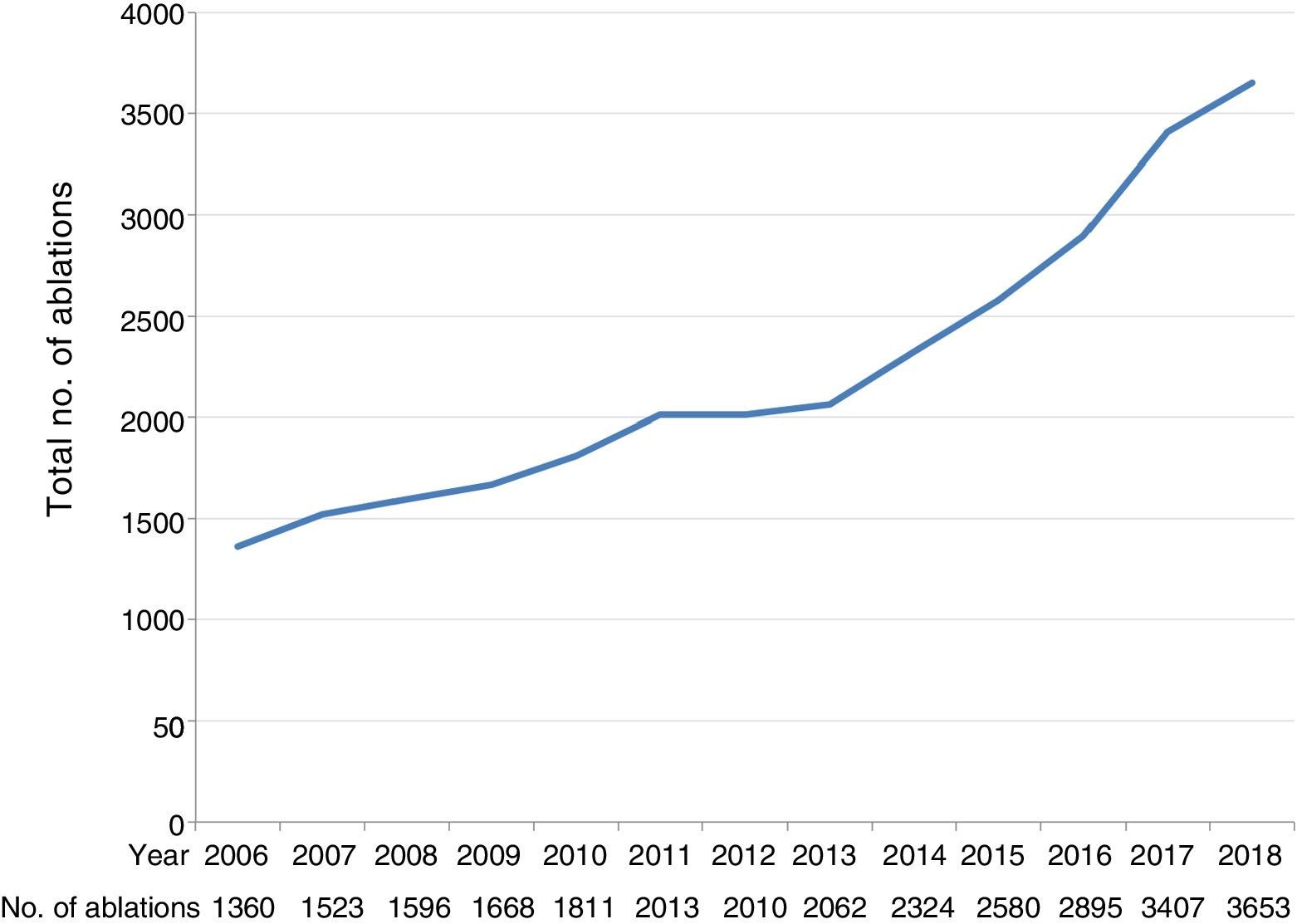

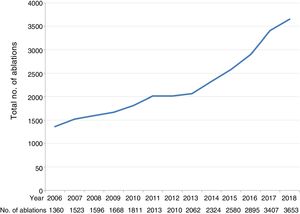

Characterization of electrophysiological proceduresIn 2017, a total of 3407 electrophysiological procedures with ablation and 774 diagnostic electrophysiological studies (not followed by ablation) were performed. The number of ablations performed in 2016 was 2895, so the year-on-year growth in the number of ablation procedures performed was 18% (Figure 3).

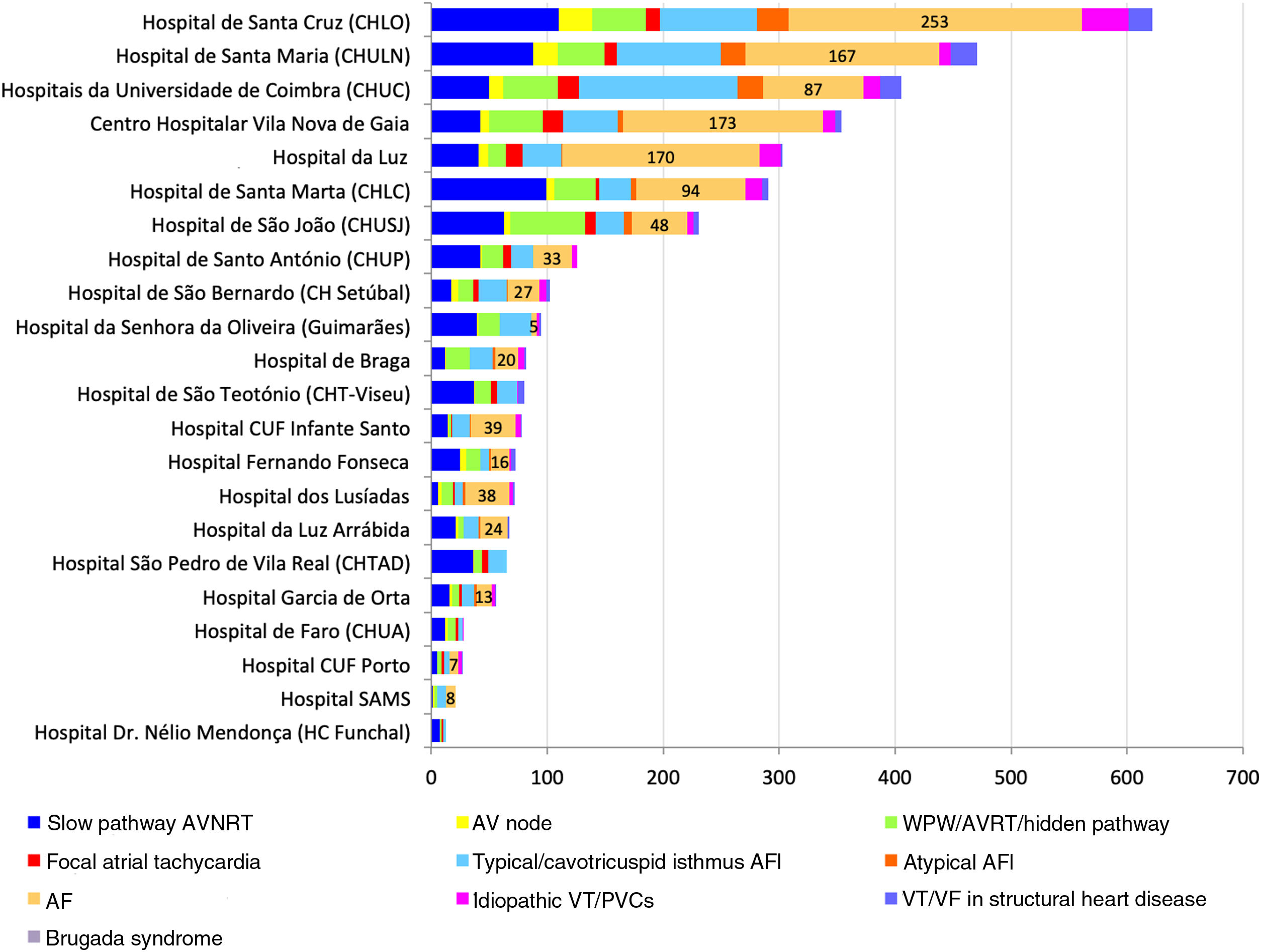

In 2017, seven centers (32% of the total) carried out more than 100 ablations, accounting for 77% of all such procedures (2623/3407). The four centers that performed more than 300 ablations accounted for 55% of these procedures (1857/3407). None of the centers performed fewer than 10 ablations/year (unlike in 2014, when this was the case in nine centers). The seven private centers performed 511 ablations, representing 15% of the total.

In 2018, 3653 ablations were performed (an increase of 8% over the previous year) and 673 diagnostic electrophysiological studies. The number of centers performing over 100 ablations increased to nine, and five centers performed over 300 ablations. The 13 centers that each performed fewer than 100 ablations accounted for 748 procedures, 20% of the total. In the six private centers 567 ablations were performed, 16% of the total.

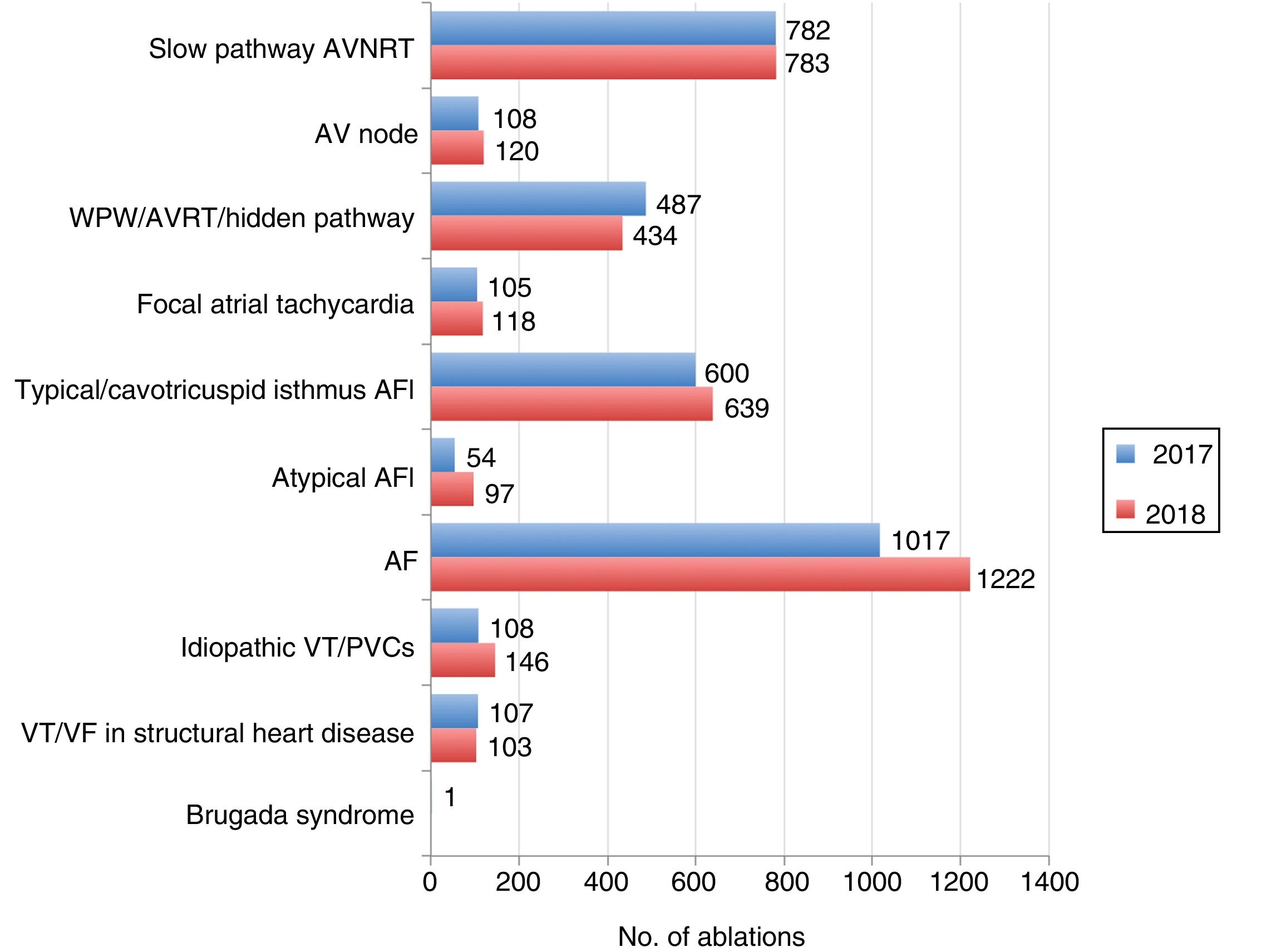

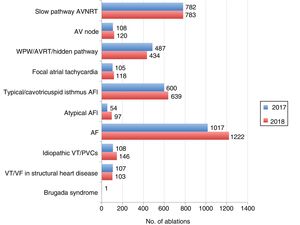

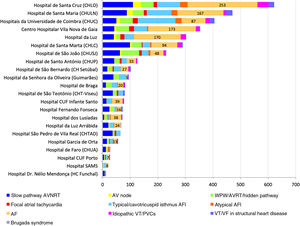

The distribution by type of ablation for 2017 and 2018 is shown in Figure 4 and a comparative analysis for the period 2016-2018 is presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Distribution by center and type of ablation is presented in Figure 5 (for 2018) and in Supplementary Figure S2 (for 2017).

Distribution of procedures by type of ablation in 2017 and 2018. AF: atrial fibrillation; AFl: atrial flutter; AP: accessory pathway; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; AVRT: atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; VF: ventricular fibrillation; VT: ventricular tachycardia; WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Distribution of procedures by center and type of ablation in 2018. AF: atrial fibrillation; AFl: atrial flutter; AP: accessory pathway; AV: atrioventricular; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; VF: ventricular fibrillation; VT: ventricular tachycardia; WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

AF ablation was the most frequently performed procedure and accounted for an increasing proportion of activity over the period under study, rising from 30% in 2016 to 36% in 2018. Conversely, the proportion of procedures for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias (atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and accessory pathway arrhythmias) fell from 40% in 2016 to 33% in 2018. Ablation of ventricular arrhythmias accounted for 6-7% of activity, a figure that did not vary significantly during the study period.

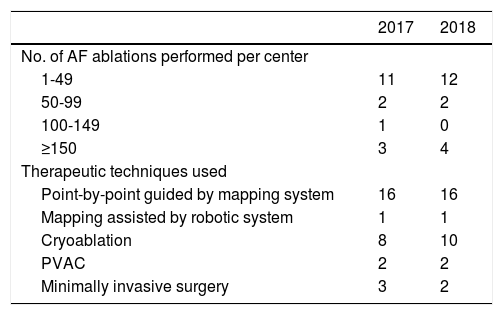

Atrial fibrillation ablationIn 2017, AF ablation was performed in 17 centers, totaling 1017 procedures (76% in public hospitals and 24% in private centers). The mean number of AF ablations was 60 and the median was 25, with considerable variation between centers (11 centers performed <50 ablations, 73% of which performed <25 procedures) (Table 1). The four centers that performed >100 procedures were responsible for 73% of all AF ablations (n=738). In 2018, 1222 AF ablations were performed in 18 centers, which represented a year-on-year increase of 20%. The mean number of AF ablations in these centers rose to 68 and the median rose to 36. The largest increase was seen in low- and medium-volume centers, the proportion of procedures performed in the four centers with most AF ablations falling to 62% (n=763) (Table 1).

Volume of atrial fibrillation ablations and therapeutic techniques used in electrophysiology centers in 2017 and 2018.

| 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of AF ablations performed per center | ||

| 1-49 | 11 | 12 |

| 50-99 | 2 | 2 |

| 100-149 | 1 | 0 |

| ≥150 | 3 | 4 |

| Therapeutic techniques used | ||

| Point-by-point guided by mapping system | 16 | 16 |

| Mapping assisted by robotic system | 1 | 1 |

| Cryoablation | 8 | 10 |

| PVAC | 2 | 2 |

| Minimally invasive surgery | 3 | 2 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; PVAC: pulmonary vein ablation catheter.

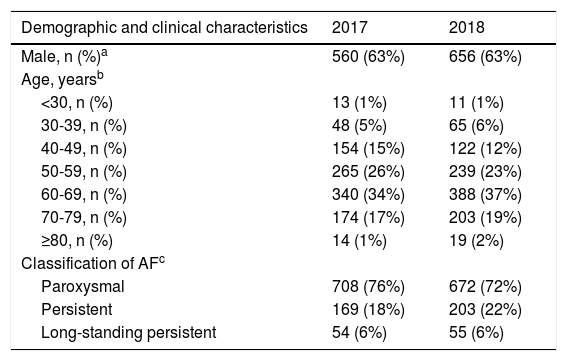

In 2017 and 2018, 63% (n=1216) of patients who underwent AF ablation were male, 60% (n=1232) were aged 50-69 years and 74% (n=1380) had paroxysmal AF (Table 2). The procedure was a first ablation in 81% of cases (n=1715). The most commonly used technique during the study period was point-by-point radiofrequency ablation guided by electroanatomical mapping (61% of procedures), but the use of cryoablation increased by 87%, rising from 128 procedures in 2017 to 239 in 2018.

Characteristics of patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation, ablation techniques used and complications reported, 2017 and 2018.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%)a | 560 (63%) | 656 (63%) |

| Age, yearsb | ||

| <30, n (%) | 13 (1%) | 11 (1%) |

| 30-39, n (%) | 48 (5%) | 65 (6%) |

| 40-49, n (%) | 154 (15%) | 122 (12%) |

| 50-59, n (%) | 265 (26%) | 239 (23%) |

| 60-69, n (%) | 340 (34%) | 388 (37%) |

| 70-79, n (%) | 174 (17%) | 203 (19%) |

| ≥80, n (%) | 14 (1%) | 19 (2%) |

| Classification of AFc | ||

| Paroxysmal | 708 (76%) | 672 (72%) |

| Persistent | 169 (18%) | 203 (22%) |

| Long-standing persistent | 54 (6%) | 55 (6%) |

| Characterization of ablation procedure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of procedured | ||

| First ablation | 764 (82%) | 951 (81%) |

| Repeat ablation | 167 (18%) | 229 (19%) |

| Therapeutic technique | ||

| Point-by-point ablation guided by EA mapping | 625 (63%) | 722 (59%) |

| Mapping assisted by robotic system | 164 (17%) | 160 (13%) |

| Cryoablation | 128 (13%) | 239 (20%) |

| PVAC | 75 (8%) | 77 (6%) |

| Minimally invasive surgery | 3 (0.3%) | 24 (2%) |

| Clinically relevant complicationse | ||

|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of any clinically relevant complication | 8 (0.8%) | 10 (0.8%) |

| Tamponade or hemopericardium requiring pericardiocentesis | 7 (0.7%) | 7 (0.6%) |

| Femoral access complications e.g. hematoma or arteriovenous fistula | 3 (0.3%) | 8 (0.7%) |

| Urgent thoracotomy | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| Atrioesophageal fistula | 0 | 0 |

| Infective endocarditis | 0 | 0 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 |

| Other clinically relevant complications | 1 (0.1%) | 5 (0.4%) |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; EA: electroanatomical; PVAC: pulmonary vein ablation catheter.

Information on gender was available for 895 patients (88%) in 2017 and for 1047 patients (86%) in 2018.

Information on age was available for 1008 patients (99%) in 2017 and for 1047 patients (86%) in 2018.

Information on type of AF was available for 931 patients (92%) in 2017 and for 930 patients (92%) in 2018.

Clinically relevant complications were reported in 18 patients (0.8%), mainly tamponade or hemopericardium requiring pericardiocentesis (n=14; 0.7%) and vascular access complications requiring intervention (n=11; 0.5%). No deaths or cases of stroke, infective endocarditis or atrioesophageal fistula were reported.

Ventricular tachycardia ablationIn 2017, ablation of VT (idiopathic, including premature ventricular contractions [PVCs], or secondary to structural heart disease) was performed in 15 centers, totaling 215 procedures (6% of all ablations). One procedure was also performed to ablate the arrhythmogenic substrate in a case of Brugada syndrome.

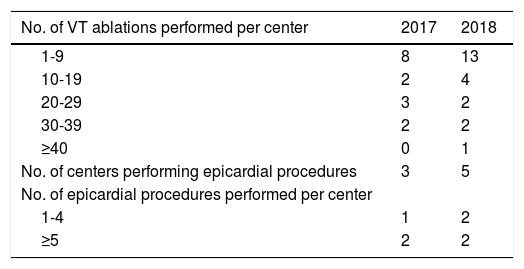

Eight centers performed fewer than 10 V T ablations, while the five centers that performed over 20 procedures were collectively responsible for 66% of all VT ablations (n=142) (Table 3). Three centers performed ablations of VT or ventricular fibrillation (VF) using an epicardial or endo-epicardial approach, in a total of 14 procedures.

Number of ventricular tachycardia ablations and experience in epicardial procedures in electrophysiology centers in 2017 and 2018.

| No. of VT ablations performed per center | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 1-9 | 8 | 13 |

| 10-19 | 2 | 4 |

| 20-29 | 3 | 2 |

| 30-39 | 2 | 2 |

| ≥40 | 0 | 1 |

| No. of centers performing epicardial procedures | 3 | 5 |

| No. of epicardial procedures performed per center | ||

| 1-4 | 1 | 2 |

| ≥5 | 2 | 2 |

VT: ventricular tachycardia.

Of the total of VF/VT ablations, 92% were performed in public centers, including 97% of those in cases of structural heart disease.

In 2018, the number of procedures increased by 16% (to 249), due to a rise in idiopathic VT ablations (from 108 in 2017 to 146 in 2018). In 2018, VF/VT ablations were performed in 19 centers, with a mean of 13 procedures (median six). Five centers performed epicardial or endo-epicardial VT ablations, in a total of 22 procedures.

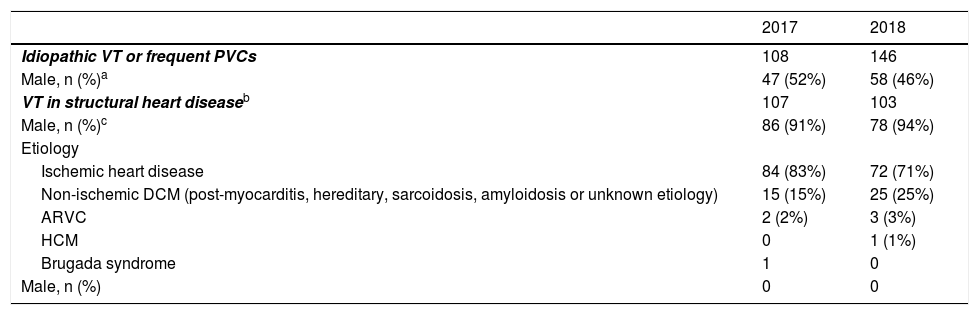

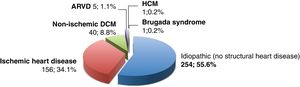

The clinical characteristics of patients undergoing VF/VT ablation are presented in Table 4. Of the 464 V T ablations carried out in 2017 and 2018, 55% (n=254) were performed for idiopathic VT or frequent PVCs, 34% (n=156) for VT in ischemic heart disease, 8.8% (n=40) in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (post-myocarditis, hereditary, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis or unknown etiology), and 1.1% (n=5) in the setting of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. One procedure was performed in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and another to ablate the arrhythmogenic substrate in a case of Brugada syndrome (Figure 6).

Characteristics of patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation, 2017 and 2018.

| 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic VT or frequent PVCs | 108 | 146 |

| Male, n (%)a | 47 (52%) | 58 (46%) |

| VT in structural heart diseaseb | 107 | 103 |

| Male, n (%)c | 86 (91%) | 78 (94%) |

| Etiology | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 84 (83%) | 72 (71%) |

| Non-ischemic DCM (post-myocarditis, hereditary, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis or unknown etiology) | 15 (15%) | 25 (25%) |

| ARVC | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| HCM | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Brugada syndrome | 1 | 0 |

| Male, n (%) | 0 | 0 |

ARVC: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; VT: ventricular tachycardia.

Distribution of ventricular tachycardia ablations by etiology in 2017 and 2018. ARVD: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Information on etiology of heart disease was available for 456 patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation (98% of these procedures).

Ablations of idiopathic VT were performed with a similar frequency in both sexes (Table 4). However, patients undergoing VT ablation in structural heart disease were predominantly male (92% men vs. 8% women; p<0.001). The number of VT ablations in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, although still low, rose between 2017 and 2018 from 15 to 25 procedures, while VT ablations in ischemic heart disease fell from 84 to 72.

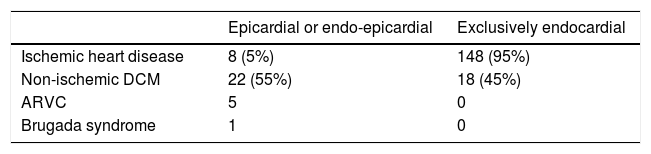

In 2017 and 2018, a total of 36 V T ablations were performed using an epicardial or endo-epicardial approach, more often in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (n=22; 61%) (Table 5). Although an epicardial approach was significantly more likely to be used in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy than in ischemic heart disease (55% vs. 5%; odds ratio: 22.6; 95% confidence interval: 8.8-58.2; p<0.0001), it should be noted that epicardial mapping was performed in eight patients with ischemic heart disease, as well as in all five patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy who underwent VT ablation and in the patient with Brugada syndrome.

Distribution of ventricular tachycardia ablations in 2017 and 2018 according to etiology and therapeutic strategy (exclusively endocardial vs. endo-epicardial).

| Epicardial or endo-epicardial | Exclusively endocardial | |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemic heart disease | 8 (5%) | 148 (95%) |

| Non-ischemic DCM | 22 (55%) | 18 (45%) |

| ARVC | 5 | 0 |

| Brugada syndrome | 1 | 0 |

ARVC: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy.

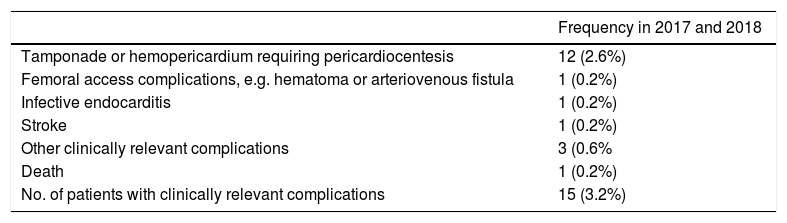

Clinically relevant complications were reported in 15 cases, a complication rate of 3.2% (Table 6). The most frequent complication was tamponade or hemopericardium requiring pericardiocentesis (n=12; 2.6%) and one death was reported as a procedural complication (0.2%).

Complications reported in ventricular tachycardia ablations in 2017 and 2018.

| Frequency in 2017 and 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Tamponade or hemopericardium requiring pericardiocentesis | 12 (2.6%) |

| Femoral access complications, e.g. hematoma or arteriovenous fistula | 1 (0.2%) |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (0.2%) |

| Stroke | 1 (0.2%) |

| Other clinically relevant complications | 3 (0.6% |

| Death | 1 (0.2%) |

| No. of patients with clinically relevant complications | 15 (3.2%) |

We hereby report data from all Portuguese centers that performed ablations in 2017 and 2018, analyzing activity in the area of electrophysiology and comparing it with data from previous years and with activity in other European countries. Activity in electrophysiology in 27 EU Member States is assessed using data from the EHRA White Book.14

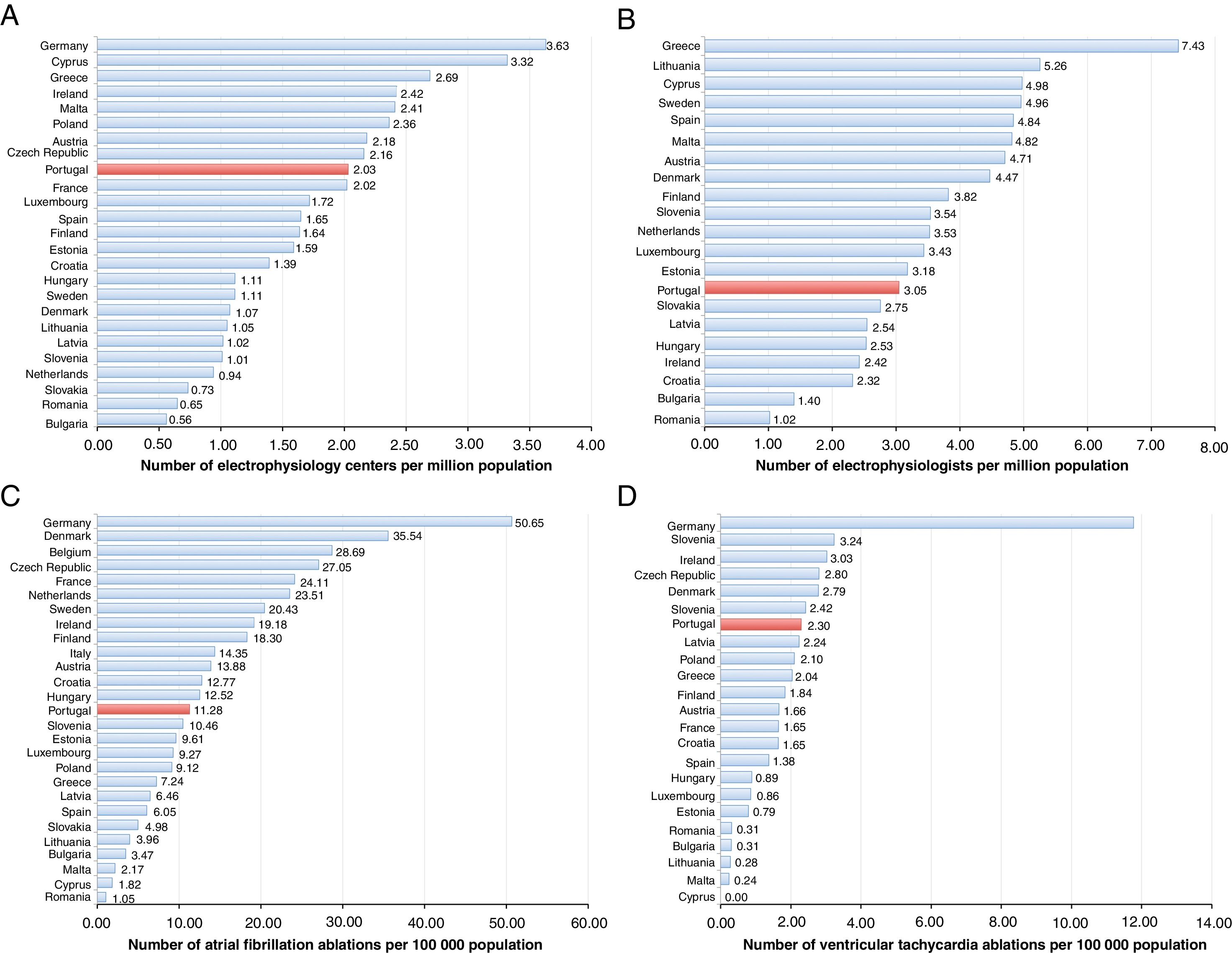

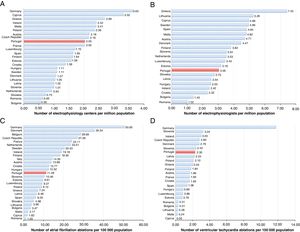

During 2017 and 2018, 22 electrophysiology centers were active in Portugal, around two-thirds of which were in public hospitals. The number of centers per million population was 2.03, slightly less than the mean for 27 EU countries (2.12 in the same period, a figure largely due to the mean of 3.63 in Germany) (Figure 7A and Supplementary Table S1).

Activity in the area of electrophysiology in Member States of the European Union (EU). (A) Number of electrophysiology centers per million population; (B) number of electrophysiologists per million population; (C) number of atrial fibrillation ablations per 100 000 population; (D) number of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation ablations per 100 000 population.

Data on Portugal for 2018 are compared to those of other EU countries for 2016 as presented in the White Book of the European Heart Rhythm Association.14 The numbers of electrophysiology centers in Belgium and Italy, and the numbers of electrophysiologists in Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Poland and the Czech Republic, are not available. The number of atrial fibrillation ablations presented for Belgium is from 2015. The numbers of ventricular tachycardia ablations performed in Belgium, Italy, The Netherlands and Sweden are not available.

The equipment in place in Portuguese electrophysiology centers is in accordance with best practice, including three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping systems, which are available in 21 of the 22 centers. With regard to human resources, the 33 electrophysiologists working in Portuguese centers correspond to 3.05 per million population, which is lower than the mean of 3.76 reported in EU countries (Figure 7B and Supplementary Table S1).

The number of Portuguese centers performing more than 100 ablations/year rose to nine in 2018, in parallel with the greater number of procedures in the five largest-volume centers. During the study period, private centers accounted for 15% of activity in the country. Despite the annual growth of 11% in these centers, all except one were low-volume centers (<100 ablations a year).

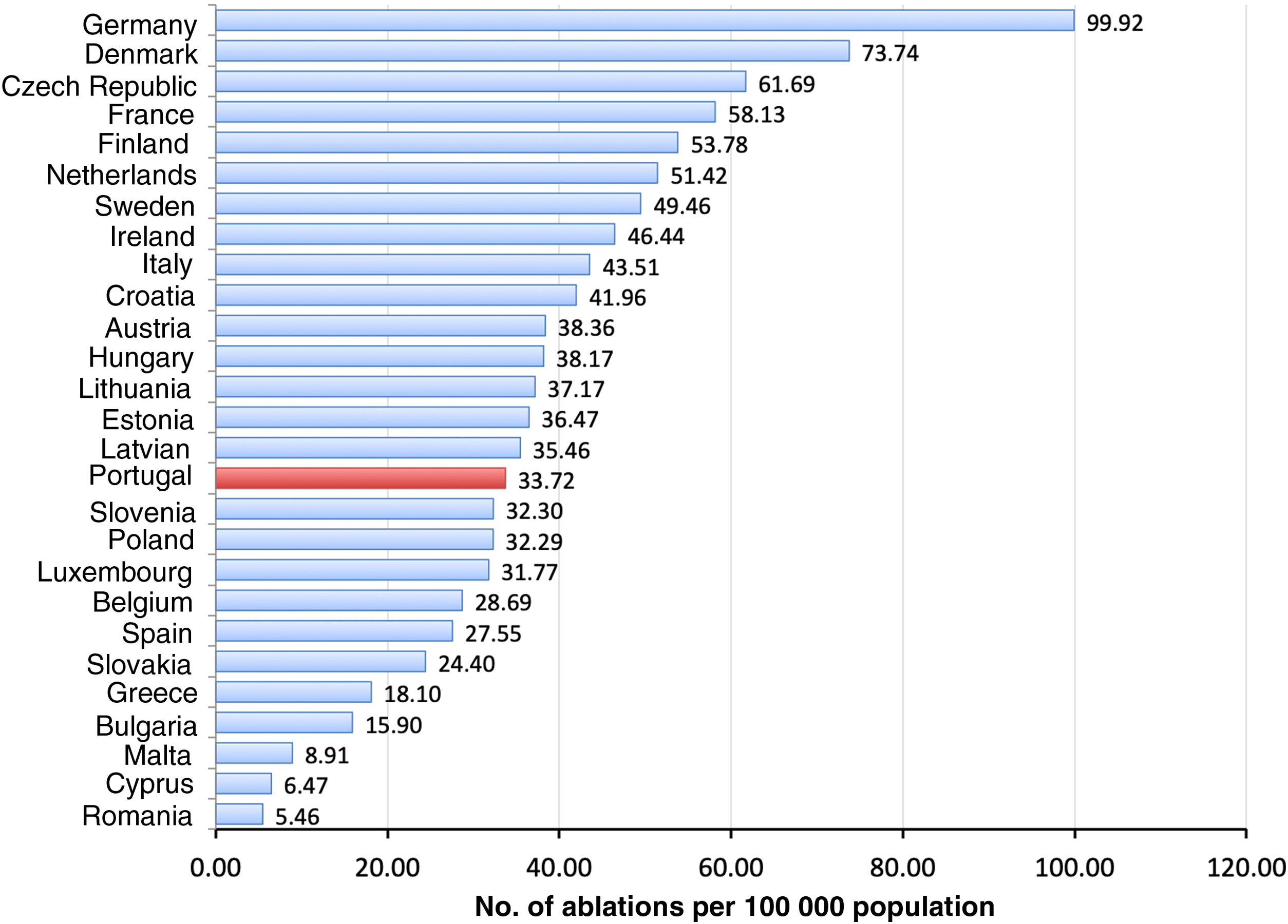

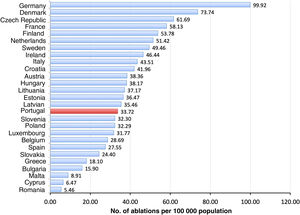

The number of ablations rose in 2017 and 2018, in line with the consistent trend observed over the last decade (Figure 3). The annual growth rates were 18% in 2017 and 8% in 2018. The 3653 ablations performed in 2018 correspond to 33.7 ablations per 100 000 population/year, which is considerably below the mean of 50.3 for the EU as a whole and three times lower than for Germany14 (Figure 8 and Supplementary Table S1).

Number of annual ablations per 100 000 population in Member States of the European Union. Data on Portugal for 2018 are compared to those of other EU countries for 2016 as presented in the White Book of the European Heart Rhythm Association.14 The data for Belgium are from 2015.

AF ablation was the most commonly performed procedure and accounted for a growing proportion of activity, reaching 36% of all procedures in 2018. AF ablations in 2018 corresponded to 11.28 procedures per 100 000 population/year, around half of the mean EU figure (21.05 per 100 000 population/year), and well below that seen in Germany (50.65 per 10 0000 population/year), but higher, for example, than in Spain (6.05 per 100 000 population/year) (Figure 7C and Supplementary Table S1).

Only four Portuguese centers performed more than 100 AF ablations/year, and these were responsible for 73% of AF ablations in 2017 and for 62% in 2018. Absolute numbers of ablations affect centers’ training capacity, since electrophysiologists in training are recommended to perform at least 50 procedures as first operator.15 It is also known that the annual numbers of ablations performed by the operator and by the center influence the rate of complications.16

Clinically relevant complications were reported in 0.8% of AF ablations in this two-year period of the registry. This figure should be treated with caution, given the retrospective nature of the data collection, which could have led to under-reporting of complications. However, it is worth noting that there were no deaths or strokes in the 2239 procedures during the study period.

A total of 465 V F/VT ablations were carried out during the study period. This number is still low, accounting for only 6% of total ablations. The mean rate of VF/VT ablations in Portugal was 2.30 per 100 000 population/year, which is also low compared to the EU mean (3.97 per 100 000 population/year) and well below the figure for Germany (11.77 per 100 000 population/year) (Figure 7D and Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, only 45% of these procedures were to treat VT in structural heart disease (107 procedures in 2017 and 103 in 2018). These numbers fall well short of what would be expected given that 10% of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators require ablation at some stage of follow-up,16 and in view of the number of such devices implanted annually in Portugal.11

ConclusionElectrophysiology in Portugal presents continuing growth in the number of catheter ablations; this growth has been consistent in both public and private centers. Nevertheless, activity remains below the mean reported in EU countries. The numbers of electrophysiology centers and of electrophysiologists are also low compared to the EU average. In 2017 and 2018, the number of complex ablations increased, and AF ablation became the most frequent type of procedure performed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects.

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data.

The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent.

The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors are grateful for the important contributions of the following specialists who provided data for the registry: Dr. Francisco Madeira (Hospital Fernando Fonseca), Dr. Francisco Morgado (Hospital dos Lusíadas), Dr. Hipólito Reis (Hospital de Santo António - CHUP), Dr. João de Sousa (Hospital de Santa Maria – CHULN; Hospital SAMS), Dr. João Primo (Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia; Hospital de São Teotónio – CH Tondela-Viseu; Hospital da Luz - Arrábia), Dr. Leonor Parreira (Hospital de São Bernardo – CH Setúbal), Dr. Luís Adão (Hospital de São João – CHUSJ), Dr. Luís Brandão (Hospital Garcia de Orta; Hospital CUF Infante Santo), Dr. Luís Elvas (Hospitais da Universidade de Coimbra – CHUC), Prof. Doutor Mário Oliveira (Hospital de Santa Marta – CHLC; Hospital CUF Infante Santo; Hospital CUF Porto), Dr. Nuno Santos (Hospital Dr. Nélio Mendonça – HC Funchal), Prof. Doutor Pedro Adragão (Hospital de Santa Cruz – CHLO; Hospital da Luz – Lisbon), Dr. Pedro Silva Cunha (Hospital da Cruz Vermelha), Dr. Renato Margato (Hospital São Pedro de Vila Real – CHTAD), Dr. Rui Candeias (Hospital de Faro – CHUA), Dr. Sónia Magalhães (Hospital de Braga), and Dr. Víctor Sanfins (Hospital da Senhora da Oliveira – Guimarães).

Please cite this article as: Cortez-Dias N, Silva Cunha P, Moscoso Costa F, Bonhorst D, Oliveira MM. Registo Nacional de Eletrofisiologia Cardíaca 2017-2018. Rev Port Cardiol. 2021;40:119–129.