We present the case of a 60-year-old woman with Brugada syndrome, permanent type 1 electrocardiographic pattern, who had previously received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. She suffered frequent syncopal episodes and multiple appropriate shocks (around five per month) due to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, refractory to quinidine therapy. Combined epicardial and endocardial electroanatomical mapping was performed with a view to substrate ablation. An area of abnormal fractionated electrograms, lasting up to 370 ms and up to 216 ms after the end of the surface QRS, was identified in the epicardium in the lower anterior part of the right ventricular outflow tract. Extensive epicardial ablation of this area, which eliminated the fractionated electrograms, led to the disappearance of the Brugada electrocardiographic pattern six weeks after ablation. Despite discontinuation of quinidine, no further ventricular arrhythmias occurred during follow-up, which is still of short duration.

É apresentado o caso de uma doente de 60 anos com síndrome de Brugada, padrão tipo 1 permanente, portadora de cardioversor-desfibrilhador, com episódios frequentes de síncope por taquicardia ventricular polimórfica/fibrilhação ventricular (cerca de cinco por mês), refratários à terapêutica com quinidina e com múltiplos choques apropriados. Foi efetuado mapeamento eletroanatómico endocárdico e epicárdico do ventrículo direito, em ritmo sinusal, confirmando-se a presença de uma área epicárdica na região anterior da câmara de saída ventricular direita com eletrogramas anómalos, fracionados e de longa duração (até 370 ms), que se prolongavam até 216 ms após o término do QRS de superfície. A ablação epicárdica alargada dessa área, com abolição dos eletrogramas anómalos, conduziu ao desaparecimento do padrão de Brugada na reavaliação eletrocardiográfica efetuada às seis semanas. Apesar da suspensão da terapêutica com quinidina, não ocorreram novas disritmias ventriculares, durante o seguimento, ainda de curta duração.

It is now over twenty years since Pedro and Josep Brugada first described the association between primary ventricular fibrillation (VF) and an electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle branch block with coved ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads in individuals with no structural heart disease.1 Since then, there has been major progress towards better understanding of the genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome, particularly the hypothesis of a voltage gradient between the endocardium and the epicardium during depolarization as the mechanism behind the electrocardiographic abnormalities and associated ventricular arrhythmias.2

The fact that electrocardiographic abnormalities were observed in the right precordial leads, and thus originating in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), soon raised the suspicion that this was the origin of arrhythmias in these patients. However, initial attempts at endocardial mapping of this region failed to identify the arrhythmic substrate. Various cases were reported in the literature in which endocardial ablation was attempted to prevent recurrence of VF in patients with Brugada syndrome and frequent ventricular extrasystoles originating in the RVOT.3–6 Nevertheless, such an approach has important limitations, given that frequent ventricular extrasystoles are not common in these patients, making them difficult to map.

Nademanee et al.7 recently described epicardial ablation of areas of delayed depolarization located in the anterior RVOT in Brugada syndrome. This study was a landmark in increasing knowledge of the pathophysiology of the syndrome, as well as providing evidence for an apparently effective therapeutic approach.

Case reportA 60-year-old woman had a history of frequent syncopal episodes for the past 10 years, unrelated to exertion or posture and usually preceded by dizziness and palpitations. Five years previously, she had suffered respiratory arrest during sleep, with generalized tonic-clonic movements. Four years ago, one of her sons suffered sudden death at the age of 39, which prompted investigation of the family. This revealed type 1 Brugada electrocardiographic pattern in the patient and another son, and both received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in May 2009.

Direct sequencing of the SCN5A gene identified no pathogenic mutation. The polymorphisms c.87A>G (p.Ala29Ala) and c.3183A>G (p.Glu1061Glu) in homozygosity and c.5457T>C (p.Asp1819Asp) in heterozygosity, previously described as non-pathogenic variants, were identified.

Frequent recurrences of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) were subsequently documented coinciding with syncopal episodes, and three appropriate shocks for VF. The frequency of arrhythmic events increased progressively, despite quinidine therapy up to the maximum tolerated dose of 400 mg/day. In the six months prior to the ablation procedure, the patient had a mean of five episodes (4–8) of polymorphic VT/VF per month.

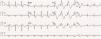

In July 2013, still under quinidine therapy, the patient underwent electrophysiological study. She presented sinus rhythm, with bifascicular block (complete right bundle branch block and left anterior hemiblock) and type 1 Brugada repolarization abnormalities in the right precordial leads and in the frontal plane leads DII, DIII and aVR (Figure 1). Occasional monomorphic ventricular extrasystoles were documented, with left bundle branch morphology, inferior axis, and QRS transition in V4, the frequency of which decreased spontaneously during the exam. During programmed ventricular stimulation, only self-limited runs of polymorphic VT (lasting up to 7 s) were induced, without VF being triggered.

12-Lead electrocardiogram showing bifascicular block (complete right bundle branch block and left anterior hemiblock), type 1 Brugada pattern (with coved ST elevation in V1–V4, terminating in inverted T wave), long QT interval (522 ms, corrected QT 568 ms) and isolated ventricular extrasystole with left bundle branch block morphology and inferior axis.

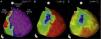

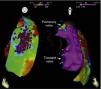

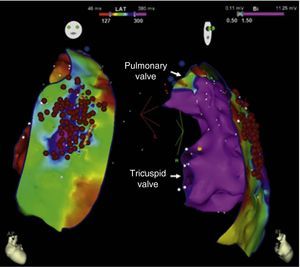

Endocardial mapping of the right ventricle was then performed in sinus rhythm, using the CARTO 3 system (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) with an irrigated catheter (Thermocool SF, Biosense Webster). No low-voltage areas were identified, nor zones with local electrograms prolonged beyond the end of the QRS complex (Figure 2). Epicardial access was obtained through subxiphoid puncture under fluoroscopic guidance, and a 9F introducer connected to a passive drainage system was inserted. High-density epicardial electroanatomical mapping of the right ventricle (304 points) and left ventricular (LV) anterior, lateral and posterior walls was performed. Voltage mapping showed normal epicardial voltages in both the left ventricle and RVOT (Figure 3). Mapping of the duration of the bipolar electrogram showed that this ended during the QRS complex in all LV regions mapped. By contrast, the bipolar electrogram terminated after the end of the QRS complex in the entire right ventricular anterior wall, and an area measuring 6.9 cm2 was identified in the anterior region of the RVOT, with fractionated potentials lasting up to 370 ms and up to 216 ms after the end of the surface QRS (Figures 3 and 4, and Video 1). Although the electrograms in this area showed mainly normal voltages, the fractionated and delayed components presented reduced voltage (<1 mV). The marked prolongation of epicardial depolarization contrasted with normal depolarization in the corresponding endocardial region (Figure 4 and Video 2).

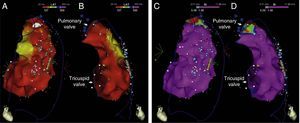

Endocardial maps of the right ventricle. Mapping of time to end of local bipolar electrogram in anteroposterior view (A) and right lateral view (B): activation of the endocardial regions ends during the surface QRS (in red), which ended 127 ms after the map reference. Mapping of bipolar voltage in anteroposterior view (C) and right lateral view (D): all endocardial regions of the right ventricle show normal voltage (>1.5 mV) (in pink).

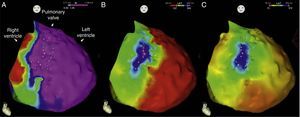

Epicardial maps in anteroposterior views: (A) mapping of bipolar voltage, showing normal voltage (>1.5 mV, in pink) in all epicardial regions of the left ventricle and right ventricular outflow tract (regions with lower voltage correspond to pulmonary and tricuspid valve planes; voltage in the epicardial apical region was not assessed); (B) mapping of time to end of the local bipolar electrogram; and (C) mapping of the duration of the local bipolar electrogram. The electrograms recorded in the left ventricle were of normal duration and ended during the surface QRS. An area measuring 6.9 cm2 was identified in the anterior region of the right ventricular outflow tract with fractionated potentials (light pink dots), of long duration (up to 370 ms) and lasting up to 216 ms after the end of the QRS.

Endo-epicardial dispersion of action potential duration in the anterior region of the right ventricular outflow tract: (A) bipolar and unipolar electrograms of the epicardium (MAP-Epi) and endocardium (MAP-Endo) recorded in contiguous sites, shown in right profile views on the endocardial (B) and epicardial (C) maps of the right ventricle. The marked prolongation of epicardial depolarization (duration 330 ms, lasting up to 216 ms after the end of the QRS) contrasts with the normal duration of depolarization in the corresponding endocardial region (102 ms).

Radiofrequency energy, in power control mode with energy output set to 35 W, was applied epicardially in the anterior RVOT over the entire area with delayed termination of local electrograms. The total duration of applications was 34 min (Figure 5). This resulted in elimination of the fractionated potentials and a slight reduction in repolarization abnormalities in V2–V3, but the Brugada pattern remained on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG). The programmed ventricular stimulation protocol was repeated, which induced runs of polymorphic VT of similar duration to that before ablation, without triggering VF.

In the 48 hours following ablation, frequent, predominantly monomorphic, ventricular extrasystoles persisted, with no other arrhythmic events. The patient was discharged medicated with propranolol 30 mg/day, quinidine therapy having been discontinued.

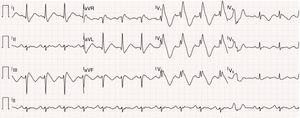

She was asymptomatic at six-month clinical assessment and reported no palpitations, fainting or syncopal episodes; no ventricular arrhythmias had been detected by the ICD. Holter monitoring recorded only 48 dimorphic and isolated ventricular extrasystoles. The electrocardiogram 43 days after ablation revealed persistence of right bundle branch block, but with significant changes in repolarization and no evidence of the previous Brugada pattern (Figure 6).

DiscussionThe clinical spectrum of Brugada syndrome is wide, ranging from asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death due to VF, which may occur late and be the first manifestation of the disease. Other common manifestations are syncope, seizures and nocturnal gasping, due to self-limited episodes of polymorphic VT/VF. Until recently, the only effective treatment for prevention of sudden death was implantation of an ICD, which is recommended in high-risk patients such as symptomatic individuals and those who have survived previous arrhythmic events.8 However, there is a high long-term incidence of complications, which occur in up to a third of cases, the most common being inappropriate shocks.9–11 In addition, although ICDs are effective in treating episodes of VF, they cannot prevent them and therefore do not improve patients’ quality of life. In patients with frequent episodes, as in the case presented, the only option is quinidine,12 a potent Ito blocker, but this drug frequently has adverse effects that make it difficult to titrate, as in our patient. Moreover, she continued to suffer frequent ventricular arrhythmias that significantly affected her quality of life, and so the decision was made to attempt ablation.

There have been various small studies of less than 10 patients3,7 and case reports4–6 of ablation to prevent VF in patients with Brugada syndrome. The initial strategy was focal endocardial ablation of ventricular extrasystoles,3–6 which are assumed to be a major trigger for ventricular arrhythmias in these patients. The origin of the ventricular extrasystoles was identified in different regions of the RVOT and local application of radiofrequency energy had varying success in preventing recurrence. This approach has important limitations due to the sporadic nature of ventricular extrasystoles, which are often not detected during electrophysiological study, as well as the possible coexistence of ventricular extrasystoles of different morphologies and origins with no pathophysiological significance. Notably, the first case described of a Brugada electrocardiographic pattern being eliminated as a result of radiofrequency ablation was of a patient in whom the absence of ventricular extrasystoles during the exam meant that pace mapping was required, followed by ablation of a large area, which suggests that extensive modification of the substrate may be curative in these patients.5

In 2007, Morita et al.13 studied radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias in an animal model of Brugada syndrome. Although the approach adopted still focused on ablation of ventricular extrasystoles, this work also highlighted the pathophysiological importance of the epicardium. The authors found that the appearance of the Brugada pattern coincided with the development of heterogeneity in the morphology and duration of epicardial action potentials, with no alterations in endocardial recordings. Ventricular extrasystoles were subsequently documented, with multiple foci distributed over a large area of the epicardium (6.1±1.4 cm2), ending in polymorphic VT. They demonstrated that epicardial (but not endocardial) application of radiofrequency energy prevented recurrence of these tachyarrhythmias. However, and in agreement with clinical observations, they pointed out that in order to achieve this effect ablation over a wide area was necessary, extensively modifying the substrate.

In a pioneering study in 2011, Nademanee et al.7 performed endocardial and epicardial mapping of the RVOT in nine patients with Brugada syndrome and frequent episodes of VF. As in the case presented, there were no alterations in voltage or duration of electrograms in the endocardium, but areas with abnormal potentials were identified in the anterior wall of the RVOT, characterized by low voltages (≤1 mV), fractionation and long duration (>80 ms), lasting well beyond the end of the surface QRS. In that study, the authors mapped the duration of the local bipolar electrogram, while we opted to map the time to the end of the bipolar electrogram, using the surface electrocardiogram as the reference and adjusting the lower edge of the region of interest on the map to the end of the QRS (Figure 3B). Re-analyzing the map employing their method produced similar results (Figure 3C). Nademanee et al.7 found that epicardial ablation of the area of abnormal potentials resulted in normalization of the Brugada pattern in seven of the nine patients, during follow-up in three of them, as in our patient. None of the patients had recurrence of polymorphic VT/VF, as in the case presented.

The type 1 Brugada repolarization abnormalities observed in our patient were not only in the right precordial leads but also in aVR and inferior leads. It has recently been reported that the presence of such alterations in the frontal plane leads is a strong predictor of risk in patients with Brugada syndrome.14 The present case also illustrates the unpredictable nature of ventricular extrasystoles as a target for ablation in this syndrome. Although our patient had frequent monomorphic ventricular extrasystoles of a morphology consistent with RVOT origin, these disappeared spontaneously during electrophysiological study, probably due to sedation; isoprenaline, commonly used to increase the incidence of extrasystoles, was not used since it is known to have an anti-arrhythmic effect in Brugada syndrome. It is also worth noting the seeming inconsistency between the long-term efficacy of substrate modification, as reflected in the disappearance of the Brugada electrocardiographic pattern and prevention of ventricular arrhythmias, and its apparent ineffectiveness in eliminating ventricular extrasystoles in the short term. Electrocardiographic monitoring during the 48 hours following ablation showed that monomorphic ventricular extrasystoles reappeared after the exam and remained constant during this period. This prompted institution of propranolol, despite discontinuation of quinidine therapy. No ventricular extrasystoles were documented on follow-up assessment, and so propranolol was also discontinued.

Finally, it is important to recognize that epicardial ablation to modify the electrophysiological substrate may have its limitations. It has recently been observed that prolongation of electrograms in the RVOT is dynamic. In a patient with a history of VF but without spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern, epicardial mapping of the RVOT identified a low-voltage area with fractionated potentials. Subsequently, during administration of ajmaline, the appearance of a type 1 pattern on the ECG coincided with progressive prolongation of local electrograms.15 The dynamic nature of depolarization abnormalities in the epicardium in patients with Brugada syndrome makes it difficult to determine how extensive substrate modification has to be to achieve clinical efficacy, or even a cure. Furthermore, a study using non-contact mapping (EnSite 3000), in which the location of the epicardial substrate was extrapolated from analysis of unipolar endocardial virtual electrograms, suggested that prolongation of depolarization beyond the end of the surface QRS could originate at sites in the RVOT that are not accessible via the epicardium, such as the septal region.16

Since follow-up in the case presented is still short, it is impossible to draw definitive conclusions as to the efficacy of the procedure. However, the disappearance of the Brugada pattern and the absence of any arrhythmic events in a patient in whom these had been extremely frequent suggests that epicardial ablation of abnormal, fractionated and prolonged potentials in the RVOT was effective as well as safe.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Cortez-Dias N, Plácido R, Marta L, et al. Ablação epicárdica para prevenção da fibrilhação ventricular em doente com síndrome de Brugada. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014;33:305.e1–305.e7.