This study reports the results of an online survey carried out by the Portuguese Society of Cardiology about its medical members’ work characteristics before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, their job satisfaction, work motivation, and burnout.

MethodsA sample of 157 participants answered a questionnaire with demographic, professional, and health-related information, followed by questionnaires on job satisfaction and motivation designed and validated for this study and a Portuguese version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and MANOVA, considering gender, professional level, and sector of activity, respectively. Multiple regression was used to assess the impact of job satisfaction and motivation on burnout.

ResultsThe only variable that distinguished participants was sector of activity. Cardiologists working in the private sector worked fewer weekly hours during COVID-19, while those in the public sector worked more. The latter expressed more desire to reduce their working hours than those who worked in private medicine and in both sectors. There were no differences between sectors in work motivation, while job satisfaction was higher in the private sector. Moreover, job satisfaction negatively predicted burnout.

ConclusionsOur findings point to a deterioration in working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, with its consequences being felt especially in the public sector, which may have contributed to the lower levels of satisfaction among cardiologists who worked exclusively in this sector, but also for those working in both public and private sectors.

Este estudo reporta os resultados de um questionário online, levado a cabo pela Sociedade Portuguesa de Cardiologia, acerca das caraterísticas do trabalho dos seus associados médicos, antes e durante a pandemia por COVID, da sua satisfação no trabalho, motivação no trabalho e burnout.

MétodoUma amostra de 157 participantes respondeu a um questionário com informação demográfica, profissional e relacionada com a saúde, seguida de questionários de satisfação no trabalho e motivação no trabalho, desenhados e validados para este estudo, e uma versão portuguesa do Maslach Burnout Inventory. Os dados foram analisados, respetivamente, através de análises descritivas, ANOVA e MANOVA, tendo em conta o género, o grupo profissional e o setor de atividade. Foi calculada uma regressão múltipla para avaliar o impacto da satisfação e da motivação no burnout.

ResultadosA única variável em que os participantes se diferenciaram foi o setor de atividade. Os cardiologistas que trabalham no setor privado reduziram o número de horas trabalhadas durante o COVID, enquanto os do setor público o aumentaram. Estes últimos expressaram mais vontade de reduzir o seu tempo de trabalho do que os que trabalham no setor privado e em ambos os setores. Não se verificaram diferenças entre os setores de atividade relativamente à motivação, enquanto a satisfação foi mais elevada no setor privado. Adicionalmente, a satisfação predisse negativamente o burnout.

ConclusõesOs nossos resultados apontam para uma deterioração das condições de trabalho durante o COVID, sendo as suas consequências sentidas especialmente no setor público, o que pode ter contribuído para os níveis mais baixos de satisfação entre os cardiologistas que trabalham exclusivamente nesse setor, mas também para os que trabalham em ambos os setores, público e privado.

It is a common perception that the requirements and challenges of medical activity impact on the well-being and health of those providing those services. According to the World Health Organization,1 work characteristics such as lack of control over work tasks, lack of support, and time pressure are important risk factors for occupational stress, burnout, and fatigue among health workers.

Concerning feelings about work, physicians’ job satisfaction – the extent to which they like or dislike different aspects of their jobs – also impacts their working lives, including their self-perception of mental and physical health, quality of care, and patient relations.2

Job satisfaction results from a cognitive process involving values, expectations, needs, and individuals’ assessments of rewards and outcomes obtained from the work environment.3 It may be intrinsic, within the worker, obtained from rewards resulting from the task and the job itself; or extrinsic, if arising from sources outside the individual, like rewards provided by the organization due to job performance, supervision or co-workers’ feedback.4–6 Job characteristics and resources,7 mental health,2 and motivation8 are among the many variables that have been studied in the domain of job satisfaction.

Work motivation has also been a widely studied concept since the early 20th century.9 It has been defined as “a set of energetic forces that originate both within as well as beyond an individual's being, to initiate work-related behavior, and to determine its form, direction, intensity, and duration”.10 Considering these drives that move people to act, different types of motivation can be found, from amotivation (absence of action due to lack of motivation and internal regulation) to intrinsic motivation (doing a task for pleasure, not for its result, reflecting inherent autonomous motivation), which can be predicted by both social environment and individual differences in causality orientations.11

Finally, professional burnout is one of the most widely studied variables among health workers’ occupational health threats. It was recently included in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon.12

The most commonly cited definition of burnout in the literature is “a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who do ‘people-work’ of some kind. It is a response to the chronic emotional strain of dealing extensively with other human beings, particularly when they are troubled or having problems.”13

In the literature there is a great diversity of predictors, both personal and work-related, of burnout in physicians, usually identified by emotional exhaustion (EE), the core dimension of burnout,14 but also depersonalization (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA).15–17 Among others, perceived organizational resources,18 work-family conflicts, and lack of support19 are significant predictors of burnout in physicians.

In view of the scarcity of studies on the characteristics of the working life of Portuguese cardiologists and their feelings about their work, in 2021 the Portuguese Society of Cardiology (SPC) launched an online survey on the subject. This paper aims to report the survey's results, deepening knowledge about the work characteristics of the SPC's medical members before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, their job satisfaction and motivation, and threats to their wellbeing, including burnout, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodsMaterialsA questionnaire was constructed to obtain participants’ demographic, professional (professional level and sector of activity), and health-related characteristics (including physical activity and history of anxiety and depression).

Job satisfaction was measured using an eight-item scale based on Blau,4 García et al.,5 and Pritchard and Peters.6 It was designed to assess career, income, work content, and decision-making autonomy, as items of intrinsic satisfaction (e.g., “Please indicate your level of satisfaction with your work content”), as well as working hours, organizational resources, organizational support, and work-family balance as items of extrinsic satisfaction (e.g., “Please indicate your level of satisfaction with your working hours”). Each item used a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from zero (dissatisfied) to three (very satisfied), with a minimum scale score of zero and a maximum of 24.

When tested through confirmatory factor analysis, the model has a higher order factor, work satisfaction, subsuming two more specific factors: intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction. The model was reasonably fitted to the data (Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square=37.97, df=19, CFI=0.977, RMSEA=0.080, SRMR=0.068), and the psychometric properties of the specific factors20 were nearly ensured for intrinsic satisfaction (average variance extracted [AVE]=0.46 and composite reliability [CR]=0.77) and ensured for extrinsic satisfaction (AVE=0.58 and CR=0.85). An overall score and two specific scores can therefore be extracted from the scale.

A work motivation scale was constructed based on self-determination theory.21 We considered that becoming a specialized physician (cardiologist) is a long-term and arduous process that presupposes, at least, identified reasons for performing the behaviors needed to achieve its goal. Identified and integrated reasons to act are found when people value the behavior and fully accept its importance in achieving their goals. Intrinsic reasons to behave are found when the activity is pleasurable without depending on the desired result.11 We therefore created three items, each using a Likert scale, representing the identified, integrated, and intrinsic motivation self-regulatory styles that make up autonomous motivation, as defined by Ryan and Deci21 (e.g., “What motivates me most in my job is that it is interesting/stimulating work”).

The saturated (df=0) one-factor model tested through confirmatory factor analysis showed that the work motivation factor had excellent psychometric properties (AVE=0.74 and CR=0.90).

To assess burnout, we used the Portuguese version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey,22 translated by Semedo23 and validated by Semedo, Diniz, and Semedo (unpublished results) in a sample of physicians and nurses.

This instrument is composed of 22 items assessing EE, DP, and PA. The dimension EE refers to feelings of being unable to give more of oneself, lack of energy, frustration, and a sense of being used. The dimension DP is reflected in the development of negative feelings and dehumanization of patients as a result of affective hardening. Reduced PA reveals itself in negative self-assessments of professional competence, which impact the ability to work, and in relationships with others. This dimension scores inversely, so high levels of PA mean high personal fulfillment.

When tested through confirmatory factor analysis, the model had a higher order factor, burnout, subsuming three more specific factors: EE, DP, and PA. The model was reasonably fitted to data (Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square=403.84, df=206, CFI=0.966, RMSEA=0.079, SRMR=0.119), and the specific factors had excellent psychometric properties: EE (AVE=0.63 and CR=0.94), DP (AVE=0.59 and CR=0.87), and PA (AVE=0.59 and CR=0.97). An overall score and three specific scores can therefore be extracted from the scale.

ProcedureThe study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Its purpose was explained to the participants, and informed consent was implicitly obtained by their anonymous and voluntary participation. The survey was made available through an SQL database (https://www.iso.org/standard/63555.html) that is the property of the SPC and linked to the SPC member database. It was sent to 1338 members, achieving a response rate of approximately 12%. This population is not fully characterized in the SPC database, which does not specify medical specialization (e.g., internal medicine) or professional level (e.g., nurses).

The study was about to be launched when the COVID-19 pandemic spread to Portugal. It was consequently postponed for about a year due to major changes in physicians’ working conditions.

It was first sent by email to all members at the end of the second COVID-19 wave,24 in mid-April of 2021. A reminder followed at the end of the month. At the end of May, data collection was closed. Participants’ sociodemographic and professional characteristics were published in the SPC's Newsletter of November 2021.

Statistical analysisIBM SPSS for Windows (version 24) was used to obtain descriptive (natural frequencies, percentages, means and ranges) and inferential statistics. The latter was used to perform between-group comparisons (factorial analysis of variance [ANOVA] and multivariate analysis of variance [MANOVA]) and predictive relationships (multiple regression) on the observed scale scores (overall and specific). The statistical assumptions were observed across all tests, and statistically significant results were supplemented by calculation of effect size. A p-level <0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

ResultsOur sample was composed of 163 participants. Six of these were excluded because of missing answers in the sociodemographic characterization (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants and of the overall population.

| Participants (%) | Overall population (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 52.20 | 40.64 |

| Men | 47.80 | 59.36 |

| Age, years | ||

| 30 or under | 9.55 | 6.08 |

| 31–40 | 22.93 | 22.66 |

| 41–50 | 13.38 | 18.25 |

| 51–60 | 23.57 | 16.58 |

| 61 or over | 30.57 | 36.43 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 17.20 | |

| Married/civil union | 72.00 | |

| Divorced | 10.20 | |

| Widowed | 0.60 | |

| Childrena | 72.6 | |

Most participants were women, were more than 50 years old, were married or in a civil union, and had children (although the survey asked the children's’ age, only one participant answered this question).

The professional characterization of participants is shown in Table 2.

Participants’ professional characteristics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Professional level | ||

| Intern | 18 | 11.50 |

| Resident | 35 | 22.30 |

| Fellow | 77 | 49.00 |

| Senior Fellow | 27 | 17.20 |

| Area | ||

| Clinical cardiology | 82 | 52.23 |

| Echocardiography | 20 | 12.74 |

| Interventional cardiology | 22 | 14.01 |

| Arrhythmology | 5 | 3.18 |

| Electrophysiology | 5 | 3.19 |

| Cardiology specializing in CHF | 11 | 7.01 |

| Intensive care cardiology | 9 | 5.73 |

| Other | 3 | 1.91 |

| Hospital levela | ||

| Non-invasive diagnostic techniques; outpatient consultation; inpatient | 48 | 30.60 |

| Hemodynamics laboratory; cardiac intensive care unit | 52 | 33.10 |

| Cardiac surgery | 41 | 26.10 |

| Sector of activity | ||

| Public | 38 | 24.20 |

| Private | 30 | 19.10 |

| Both | 89 | 56.70 |

| Head of functional unitb,f | 61 | 38.85 |

| Teachingc,f | 70 | 44.59 |

| Academic careerd,f | 33 | 21.02 |

| Engaged in researche,f | 78 | 49.68 |

CHF: congestive heart failure.

The most frequent professional characteristics of participants were being a fellow, being a clinical cardiologist, working in both public and private sectors, teaching, and being engaged in research.

Since data collection continued during the pandemic, information was available on how it impacted work time, including working hours and attending activity. Table 3 shows how these physicians spent their weekly work time.

Characterization of participants’ work time (in hours per week).

| Characteristic | n | Mean | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workloada,b | |||

| Public sector (before COVID-19) | 35 | 46.77 | 35–80 |

| Public sector (during COVID-19) | 36 | 48.51 | 35–80 |

| Private sector (before COVID-19) | 28 | 35.07 | 4–72 |

| Private sector (during COVID-19) | 27 | 32.89 | 6–72 |

| Both sectors (before COVID-19) | 83 | 54.06 | 12–117 |

| Both sectors (during COVID-19) | 82 | 53.94 | 9–100 |

| Hours spent on administrative work in the public sector | 38 | 8.11 h | 0–40 |

| Hours spent on administrative work in the private sector | 30 | 2.43 h | 0–15 |

| Hours spent on administrative work in both sectors | 89 | 5.98 h | 0–20 |

| Would you reduce your working hours if you could?c | 98 (62.82%) | ||

| Public sector | 28 (73.68%) | ||

| Private sectord | 9 (31.03%) | ||

| Both sectors | 61 (68.54%) | ||

Before COVID-19, physicians working exclusively in the public sector spent around 11 more hours per week on their professional activity than those in the private sector. Due to increased activity in the public sector and reduced activity in the private sector, this difference widened to around 16 hours per week during COVID-19. For those who worked in both sectors, the weekly number of hours did not differ before and during COVID-19.

Table 3 also shows the mean number of hours of administrative work spent weekly by physicians in public, private, and both sectors. The figure was highest in the public sector. Moreover, most of the participants expressed a desire to reduce their working hours, especially those working in the public sector.

Further analyzing how work was affected by COVID-19, data on attending activity is presented in Table 4.

Effects of COVID-19 on attending activity and income.

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Attending activitya,b | ||

| Not affected | 4 | 2.90 |

| Slightly affected | 35 | 25.20 |

| Moderately affected | 67 | 48.20 |

| Severely affected | 33 | 23.70 |

| Working with infected patientsb,c | ||

| Never | 20 | 14.30 |

| Occasionally | 111 | 79.30 |

| Daily | 9 | 6.40 |

| Participation in necessary work adjustmentsd,e | 56 | 41.20 |

| Professional autonomyb,f | ||

| Reduced | 8 | 5.80 |

| Maintained | 120 | 86.30 |

| Increased | 11 | 7.90 |

| Income in public sectorb,g | ||

| Reduced | 3 | 2.70 |

| Maintained | 104 | 92.00 |

| Increased | 6 | 5.30 |

| Income in private sectorb,h | ||

| Reduced | 64 | 60.38 |

| Maintained | 36 | 33.96 |

| Increased | 6 | 5.66 |

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the attending activity of participants, most of whom worked occasionally with infected patients. Concerning work organization, less than half of physicians participated in the definition of necessary work adjustments, and their professional autonomy was mostly reduced. While income in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic remained almost constant, in the private sector more than 60% of participants reported a loss of income.

A characterization of participants regarding certain health-related issues is shown in Table 5.

Characterization of participants’ health-related issues.

| Characteristic | n | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Weekly hours spent on exercise/sportsa | 143 | 1 h 43 min |

| Weekly hours spent on hobbiesa | 145 | 2 h 18 min |

| Weekly hours spent on cultural activitiesa | 145 | 1 h 24 min |

Time spent on leisure activities ranged from about one and a half to two and a quarter hours weekly. Around one-third of participants (n=56) reported not playing any sports or taking exercise, and almost the same number (n=58) spent no time on hobbies. The number who spent no time on cultural activities was even higher (n=70).

Concerning health-related indicators, less than half of participating physicians reported satisfaction with sleep quality, and approximately a quarter had a history of anxiety and/or depression.

Concerning feelings about the profession of cardiologist, participants answered the question “‘To what extent do you recommend this specialty?” as presented in Supplementary Table 1. Cardiology as a specialty was moderately to highly recommended by more than 90% of participants.

Regarding job satisfaction, work motivation, and burnout, results are presented by gender, professional level, and sector of activity.

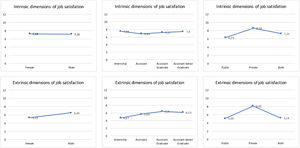

Estimated marginal means for the intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions of job satisfaction are presented in Figure 1. Results of MANOVA corroborate visual inspection of the figure: sector of activity (panels C and F) showed the only significant between-group difference for both intrinsic [F(2, 137)=7.69, p=0.001, ηp2=0.10] and extrinsic [F(2, 137)=9.67, p<0.001, ηp2=0.13] dimensions.

Following the previous analysis, an item-by-item decomposition was performed to examine nuances within dimensions of intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction. Statistical analysis showed very similar results between the Kruskal-Wallis and ANOVA tests, and so we present the ANOVA results in Table 6 with post-hoc tests in Table 7 to assess differences by sector of activity.

Results of ANOVA for intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction items by sector of activity.

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career (intrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 4.89 | 2 | 2.44 | 4.27 | 0.016 |

| Error | 88.13 | 154 | 0.57 | ||

| Income (intrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 10.06 | 2 | 5.03 | 8.28 | 0.000 |

| Error | 93.58 | 154 | 0.61 | ||

| Work content (intrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 0.13 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.874 |

| Error | 74.57 | 154 | 0.48 | ||

| Decision-making autonomy (intrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 5.19 | 2 | 2.60 | 6.09 | 0.003 |

| Error | 65.65 | 154 | 0.43 | ||

| Working hours (extrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 11.02 | 2 | 5.51 | 11.26 | 0.000 |

| Error | 75.39 | 154 | 0.49 | ||

| Organizational resources (extrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 25.56 | 2 | 12.78 | 23.77 | 0.000 |

| Error | 82.79 | 154 | 0.54 | ||

| Organizational support (extrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 11.60 | 2 | 5.80 | 9.08 | 0.000 |

| Error | 98.31 | 15 | 0.64 | ||

| Work-family balance (extrinsic) | |||||

| Between groups | 10.01 | 2 | 5.01 | 8.87 | 0.000 |

| Error | 86.88 | 154 | 0.56 | ||

Results of multiple comparisons for intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction items by sector of activity.

| Sector | Career (intrinsic) | Income (intrinsic) | Decision-making autonomy (intrinsic) | Working hours (extrinsic) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDiff | SE | p | MDiff | SE | p | MDiff | SE | p | MDiff | SE | p | |

| Public–private | −0.54 | 0.18 | 0.013 | −0.70 | 0.19 | 0.001 | −0.40 | 0.16 | 0.019 | −0.73 | 0.17 | 0.000 |

| Public – both | −0.19 | 0.15 | 0.600 | −0.09 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 1.00 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 1.00 |

| Private – both | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.095 | 0.61 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.002 | 0.64 | 0.15 | 0.000 |

| Sector | Organizational resources (extrinsic) | Organizational support (extrinsic) | Work-family balance (extrinsic) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDiff | SE | p | MDiff | SE | p | MDiff | SE | p | |

| Public–private | −0.97 | 0.18 | 0.000 | −0.70 | 0.20 | 0.001 | −0.62 | 0.18 | 0.003 |

| Public – both | 0.07 | 0.14 | 1.00 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 1.00 |

| Private – both | 1.04 | 0.15 | 0.000 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.000 | 0.65 | 0.16 | 0.000 |

Tests with Bonferroni correction.

Except for work content, all other aspects of job satisfaction presented significant differences between at least two sectors of activity. Multiple comparisons for the intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction items were then carried out to determine which differences were significant (Table 7).

Differences were found between the three groups. Compared with those in the public sector, job satisfaction was in all cases significantly higher in physicians working exclusively in the private sector. Similar results were found between those working in the private sector and in both sectors, except for career satisfaction, in which no differences were observed.

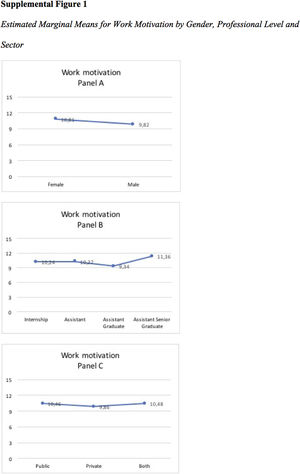

Regarding work motivation, estimated marginal means are presented in Supplementary Figure 1. Factorial ANOVA results corroborate visual inspection of the figure: no significant between-group differences were found.

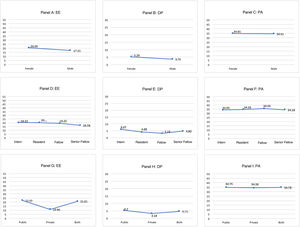

Estimated marginal means for the burnout dimensions are presented in Figure 2. The results of MANOVA corroborate visual inspection of the figure: the sector of activity (panel G) showed the only significant between-group difference, and only in EE [F(2, 137)=6.06, p=0.003, ηp2=0.08], between public and private (lower in the private sector), and private and both sectors (lower in the private sector).

According to the cut-offs defined by the authors of the Maslach Burnout Inventory,22 high EE is defined as ≥29, moderate as 18–29, and low as ≤17. A high DP is defined as ≥12, moderate as 6–11, and low as ≤5, while high PA is defined as ≥40, moderate as 39–34, and low as ≤33. Thus, in our overall sample, cardiologists presented moderate levels of EE (mean 21.21; SD 12.43), low levels of DP (mean 5.10; SD 5.35), and low-to-moderate levels of PA (mean 34.13; SD 9.25).

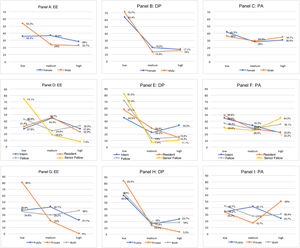

For a detailed analysis, Figure 3 presents burnout by level (high, moderate, and low) in its three dimensions (gender, professional level, and sector of activity). The clearest differences can be observed in EE, in which more than half of male participants (panel A), around three-quarters of Senior Fellows (panel D) and four-fifths of physicians in the private sector (panel G) present the lowest levels. No participants working in the private sector reported high EE (panel G), and only 3.3% reported high DP (panel H), while their PA was the highest of the three groups (panel I).

Finally, the test results for multiple regression analysis of work motivation and job satisfaction (overall scores) to predict relationships with burnout (overall score) showed that the regression model was significant [F(2, 154)=7.36, p<0.001, R2a=0.08], mainly due to the only significant relationship observed: the negative prediction of job satisfaction for burnout (B=−1.23, EP=0.34, β=−0.28, t(156)=−3.61, p<0.001, dz=−0.29).

DiscussionThis study aimed to provide a general characterization of the professional life of Portuguese cardiologists. To achieve this goal, sociodemographic, professional, and health-related data were analyzed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of weekly hours worked increased in the public sector, decreased in the private sector, and did not change for those working in both sectors, while income fell in the private sector. COVID-19 also affected the attending activity of physicians, with the majority not participating in the definition of necessary work adjustments, which led to them feeling that their professional autonomy was reduced.

Almost two-thirds of participants stated that they would like to reduce the number of hours they worked, especially those working in the public sector. Interestingly, physicians working in both sectors, and having the highest number of weekly working hours, less often reported a wish to reduce their working hours than those working exclusively in the public sector. This finding leads to the hypothesis that working in the private sector has a buffering effect on their desire to reduce work time, perhaps due partly to income as a major factor.

Health-related indicators showed predominantly low satisfaction with sleep quality and around 25% prevalence of history of anxiety and depression. A large proportion of physicians reported that they did not play sports or do any leisure activities. It should be recalled that these results were obtained during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job satisfaction, work motivation, and burnout were analyzed by gender, professional level, and sector of activity.

Regarding job satisfaction, the only significant differences were between the public and private sectors, and the private and both sectors, with the private sector expressing the most satisfaction. These differences extended to intrinsic (career, income, autonomy in decision-making) and extrinsic (working hours, organizational resources, organizational support, and work-family balance) satisfaction. To our knowledge, there have been no studies on Portuguese physicians that compare job satisfaction by sector of activity. However, research on health professionals that included physicians reached similar results, showing higher levels of satisfaction among those working in the private sector.25

Similar patterns to ours, of higher job satisfaction in the private sector, have been found in other countries.16,26–28

Differences in physicians’ motivation did not reach statistical significance in any of the compared demographic and work-related variables. The absence of differences between genders is in line with the result observed by van der Burgt et al.,29 which also did not reach statistical significance when comparing autonomous motivation in female and male physicians. Although they did not study professional level as we did, the same authors29 compared autonomous motivation according to years of experience, a variable most probably correlated with professional level, and found no differences. Regarding sector of activity, differences in physicians’ motivation were found between public and private sectors, favorable to the latter.30 However, the instrument they used to measure motivation was supported by different theoretical models and items, and thus its results cannot be compared to ours.

As with job satisfaction, results for burnout differed only in terms of professional sector. When comparing burnout by gender, some previous studies are generally inconclusive,15 while others appear to reveal a tendency for DP to be worse in men,15–17 and for EE to be higher in women,17,31 although our data did not corroborate those differences.

The same lack of statistical difference was found between professional levels. Other authors have found that residents present an increased risk of EE and DP and lower PA, a pattern that reverses with increasing time spent in practice (both general practitioners and specialists) and age.15,16 A high prevalence of burnout was also found in a Portuguese sample of residents in oncology specialties.32

Regarding sector of activity, physicians working in the private sector presented significantly lower levels of EE. A similar result was reported by Ozyurt et al.,16 who also found lower DP and higher PA.

The model used to test the predictive effect of job satisfaction (overall score) and work motivation on burnout (overall score) showed that only the former was a significant and negative predictor, a finding that cannot be compared with others using regression analysis on overall scores. To the best of our knowledge, there have no similar studies. Nevertheless, considering that high burnout is defined as high EE and DP and low PA,13 in a literature review Williams and Skinner2 found various studies with negative correlations between physicians’ job satisfaction and EE and DP and positive correlations with PA, which indirectly supports our findings.

However, our results should be treated with caution, since sampling (non-probabilistic) and sample size (small, according to rules of thumb, as well as taking into account the population of SPC members) were not optimal. Also, data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Replicating this survey with other samples of cardiologists post-COVID-19 would allow us to determine whether the present results were due to constraints arising from the circumstances of the pandemic or to structural working conditions.

ConclusionThe COVID-19 pandemic has increased emotional demands on health professionals, making them feel more emotionally exhausted, stressed, and depressed than in pre-COVID-19 times.33 Our results point to a deterioration in working conditions during COVID-19, and its consequences were felt especially in the public sector.

This deterioration may have contributed to the lower levels of intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction and higher levels of EE observed among physicians in the public sector. At the same time, job satisfaction, as a whole, had a positive impact on burnout reduction, highlighting the importance of work-related factors such as income and organizational resources in reducing occupational health threats, like burnout, thus contributing to workers’ wellbeing.

Nevertheless, at a time that demonstrates the critical importance of physicians for the national health system, our results underline the importance of keeping these professionals satisfied by improving their working conditions and wellbeing.

FundingThe authors have no funding to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.