Aortic stenosis (AS) with a valve area (AVA) <1 cm2 but mean gradient (MG) <40 mmHg in the presence of normal ejection fraction (LVEF ≥50) is a matter of concern, when considering the true severity of AS.1,2 We hypothesized that exercise echocardiography (ExE) could offer additional information by two pathways: the detection of LV systolic dysfunction and changes in AV hemodynamics.

Consecutive asymptomatic, or low symptomatic/equivocal symptoms patients with paradoxical low gradient (LG) severe AS were studied. We measured AVA, maximum and MG, mitral regurgitation (MR), systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) and LV early filling/early mitral annulus septal systolic movement (E/e′) ratio3 (EPIC 7, Philips). Moderate MR was considered significant.

Patients underwent a treadmill ExE (Bruce protocol 76%).4,5 Peak imaging assessed LV systolic function (global, regional) and post-exercise the rest of measurements (MR, E/e′, AVA, gradients, sPAP). The study was approved by our Ethics Committee. End points were all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, admittance for unstable coronary syndrome or for cardiac failure, or symptomatic progression leading to AV replacement and/or coronary revascularization.

Table 1 shows clinical characteristics and ExE data; low-flow LG-AS was observed in 17 patients (38%), and normal-flow LG (>/=35 ml/m2) in 28 (62%). AVA at exercise was evaluated in 33 subjects, as bad tracing quality/technical reasons prevented assessment in 12. Findings of moderate AS at exercise (AVA ≥1 cm2 plus MG <40 mmHg) were observed in 10/33 (30%) patients and of definitively severe AS (AVA <1 cm2; MG ≥40 mmHg) in 7/33 (21%), with no differences in % between low-flow and normal flow. AVA and MG at rest were worse in patients with definitively severe AS in exercise (p<0.05 both) and increase in blood pressure lower (p=0.08). Angiography performed in 32 patients showed coronary artery disease (CAD) in 15 (exercise WMAs in nine) and was normal in 17 (exercise wall motion abnormalities [WMAs] in three).

Clinical characteristics in the overall group; and resting and exercise echocardiography data, and changes with exercise in subgroups (low-flow low gradient and normal-flow low-gradient AS).

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age, y | 74±12 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 32 (71) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (29) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 33 (73) |

| Hypercholesterolemia (51%) | 23 (51) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (20) |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 13 (29) |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 10 (22) |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 6 (13) |

| AECI/ARAs, n (%) | 20 (44) |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 1 (2) |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 7 (16) |

| Betablockers, at the time of the ExE, n (%) | 7 (16) |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 16 (36) |

| Chest pain | 10 (22) |

| Equivocal/low grade dyspnea | 12 (27) |

| Any chest pain plus equivocal dyspnea | 7 (15) |

| Resting echocardiography | |

| Myocardial thickness, mm | 12.3±2.4 |

| Global LV longitudinal strain | −19.3±4.0 |

| Calcium score ≥2* | 15 (34) |

| Resting WMAs | 3 (7) |

| Exercise echo data | p values intergroup (rest, exercise) | |

|---|---|---|

| >85% of the age-predicted maximum heart rate, n (%) | 37 (82) | NS |

| LFLG | 16 (94) | |

| NFLG | 21 (75) | |

| Achieved METs | 6.6±2.2 | NS |

| LFLG | 6.2±2.2 | |

| NFLG | 6.7±2.1 | |

| Symptoms with exercise, n (%) | 14 (31) | NS |

| LFLG | 4 (24) | |

| NFLG | 10 (36) | |

| Blunted blood pressure response, n (%) | 17 (38) | NS |

| LFLG | 4 (24) | |

| NFLG | 13 (46) | |

| Ischemia, n (%) | 15 (33) | |

| LFLG | 4 (24) | NS |

| NFLG | 11 (39) | |

| Changes from rest to exercise | Rest | Exercise | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 79±18 | 139±20 | |

| LFLG | 89±19 | 145±24 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 73±14 | 135±16 | Ex. NS |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 136±28 | 164±31 | |

| LFLG | 135±31 | 170±28 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 137±26 | 160±32 | Ex. NS |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 61±7 | 64±8 | |

| LFLG | 57±5 | 64±10 | Rest 0.001 |

| NFLG | 63±6 | 64±8 | Ex. NS |

| Wall motion score index | 1.03±0.15 | 1.13±0.24 | |

| LFLG | 1.06±0.24 | 1.17±0.33 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 1.00±0.03 | 1.10±0.16 | Ex. NS |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.84±0.16 | 0.95±0.25 | |

| LFLG | 0.81±0.19 | 0.86±0.14 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 0.85±0.23 | 1.00±0.25 | Ex. 0.06 |

| Mean aortic gradient (mmHg) | 27±7 | 35±9 | |

| LFLG | 25±8 | 34±11 | Rest 0.08 |

| NFLG | 28±6 | 35±7 | Ex. NS |

| Maximal aortic gradient (mmHg) | 51±12 | 68±19 | |

| LFLG | 48±15 | 63±23 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 52±10 | 71±15 | Ex. NS |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure, mmHg (n) | 42±13 (23) | 56±18 (21) | |

| LFLG | 42±13 | 54±17 | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 42±14 | 58±13 | Ex. NS |

| E/e′>15 and/or restrictive pattern | 17 (38) | 18 (40) | |

| LFLG | 8 (47) | 7 (41) | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 9 (32) | 11 (39) | Ex. NS |

| Moderate or severe MR, n (%) | 4 (9) | 3 (7) | |

| LFLG | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | Rest NS |

| NFLG | 3 (11) | 2 (8) | Ex. NS |

METs depicts metabolic equivalents; ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARAs: angiotensin receptor antagonists; LFLG: low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis; NF: normal flow; Ex.: exercise.

The aortic valve calcium score was semi-quantitatively measured by echocardiography, scoring small area of calcification as 1, moderate extension affecting 1–2 valves as 2, and extensive calcification affecting 2–3 valves as 3; ExE: exercise echocardiography; MR: mitral regurgitation; WMAs: wall motion abnormalities.

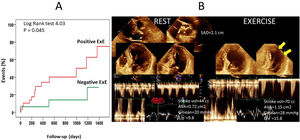

During follow-up of 22±18 months, there were 29 events. Resting wall motion score index (WMSI), metabolic equivalents, left ventricular ejection fraction and WMSI at exercise, Δ WMSI, abnormal ExE, significant MR at exercise, and digoxin were associated with events. Independent predictors were digoxin (HR=44.8, p=0.003), resting WMSI (HR=87.5, p=0.001), Δ in WMSI (HR=11.3, p=0.002), and significant exercise MR (HR=6.1, p=0.006). Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier curves according to ExE results, and an example of moderate AS performance at exercise.

(A) Event-free survival Kaplan-Meier curves for patients with normal and abnormal exercise echocardiography findings. (B) Example of a patient with low-gradient severe AS, that developed hemodynamic data of moderate AS with exercise. Arrows: lateral ischemia. Post-test angiography demonstrated CAD.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating treadmill ExE for defining outcomes in LG-AS. The main findings were that ExE was useful to detect outcome mainly by demonstrating exercise WMAs but failed in exploring the benefit of AV hemodynamics. Our data emphasize that in this scenario, it is not just the AV disease that matters, but that CAD is commonly associated and can affect the outcome.

One study employed dobutamine stress or supine bicycle in paradoxical LG-LF AS,6 finding greater severity with stress (smaller AVA, smaller projected AVA, and higher gradients) in patients in whom the anatomical extracted AV during surgery showed greater severity. Also, they observed that projected AVA was an independent predictor of outcome. Hence, exercise could be of interest for assessing outcome, suggesting that lower gradients during exercise, and greater AVA would be data of less severe outcome, therefore, reclassifying these patients.

Some of our patients had findings of non-severe AS such as limited hypertrophy and AV calcification, and moderate AS at exercise. On the other hand, symptom explanations can come from diastolic dysfunction, as well as from the aforementioned associated ischemic CAD. Although our research failed to find any association between exercise hemodynamics and outcome, we would like to encourage others to further look for insights into LG-AS. However, an ExE for assessing ischemia can offer prognostic information on these subjects.

Limitations included the small sample that prevented the study of certain relationships, such as those derived from assessment of AV parameters. AVA at exercise was not assessed in all patients; and ExE results were available to the responsible clinicians.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have read and approved the manuscript. It has not been published and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. Jesús Peteiro and Alberto Bouzas-Mosquera participated in the design, data acquisition, and data analysis, whereas Lucia Valmisa revised it critically and gave final approval.

FundingThis work was supported by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Project of Clinical Research in Cardiology Dr. Pedro Zarco 2017).

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interest to disclose.