Cardiac arrest (CA) is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Many studies focus on survival, but few explore the outcomes. The aim of this study is to analyze the survival curve, independence, quality of life, and performance status after CA.

MethodsThis retrospective study included adults admitted to the intensive care unit of Cova da Beira University Hospital Center after CA between 2015 and 2019. We analyzed patient records and applied a questionnaire including EuroQoL's EQ-5D-3L and ECOG performance status.

ResultsNinety-seven patients were included (mean age 75.74 years). Thirty-one patients (32.0%) survived to hospital discharge. There was a significant loss of independence for activities of daily living, with 50.0% of those previously independent becoming dependent and 47.5% of those previously at home being institutionalized. Diabetes, female gender, and length of hospital stay were especially impactful on these findings. One year after CA, only 20.6% were alive and only 13.4% (65% of the one-year survivors) were independent. Nine patients answered our questionnaire. Mean EQ-5D quality of life index (0.528±0.297) and the most affected domains (‘Pain/discomfort’ and ‘Anxiety/depression’) were similar to the Portuguese population aged >30 years. However, 66.6% reported a decline in their quality of life. Lastly, seven respondents had a good performance status (ECOG 0-1).

ConclusionsThere was a significant loss of independence after CA. Moreover, despite the acceptable performance status and the quality of life results being similar to the general population, there was a perceived deterioration post-CA. Ultimately, we emphasize the need to improve care for these patients.

A paragem cardiorrespiratória (PCR) associa-se a morbilidade e mortalidade elevadas. Muitos estudos focam-se na sobrevivência, porém poucos exploram a qualidade de vida. O objetivo deste estudo é analisar o tempo de sobrevida, autonomia, qualidade de vida e performance status pós-PCR.

MétodosEstudo retrospetivo incluindo os adultos admitidos na UCI do Centro Hospitalar Universitário Cova da Beira após PCR entre 2015 e 2019. Analisaram-se os processos clínicos e aplicou-se um questionário que incluiu o EQ-5D-3L da EuroQoL e o ECOG performance status.

ResultadosForam incluídos 97 doentes (idade média 75,74 anos). A sobrevivência à alta foi de 32% e um ano após PCR foi de 20,6%. Verificou-se uma perda de autonomia significativa, sendo que 50% dos previamente autónomos ficaram dependentes e 47,5% dos que viviam no domicílio foram institucionalizados. A diabetes mellitus, o sexo feminino e tempo de internamento foram as variáveis com mais impacto nestes achados. Um ano após PCR, 65% eram autónomos, correspondendo a apenas 13,4% do total da amostra. Nove doentes participaram no questionário. O índice de qualidade de vida EQ-5D (media = 0,528 ± 0,297) e os domínios mais afetados («Dor/mal-estar», «Ansiedade/Depressão») foram semelhantes aos da população portuguesa ≥30 anos. Contudo, 66,6% reconheceram um declínio subjetivo. Adicionalmente, sete apresentavam uma boa performance status (ECOG 0-1).

ConclusõesConstatou-se uma perda significativa de autonomia após PCR. Também nos participantes do questionário houve um declínio da qualidade de vida, apesar da performance status satisfatória e resultados semelhantes à população geral. Assim, destacamos a necessidade de melhoria dos cuidados a estes doentes.

Cardiac arrest (CA) is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and is a major cause of death in Europe.1,2 The most comprehensive study in Europe reports 8% survival to discharge for out-of-hospital CA (OHCA) overall, and 26.4% survival for those admitted to the hospital.3 Studies on in-hospital CA (IHCA) are limited and report survival rates ranging from 15% to 34%.1 Although successful resuscitation involves return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), the sequelae of post-CA syndrome must also be taken into account. This syndrome comprises hypoxic–ischemic brain injury, myocardial dysfunction, systemic ischemia/reperfusion response, and persistence of the precipitating condition. It is therefore also essential to take measures to improve neurologic outcomes and quality of life post-CA.4–6

CA has a wide range of neurologic repercussions, affecting attention and cognitive function, and even leading to dementia or depression.2,6,7 Many factors influence neurologic outcomes, such as event location, initial rhythm, time until cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and CPR duration.2 Nonetheless, the cerebral performance category (CPC) at 6–12 months post-arrest is often classified as ‘good’, especially in countries where withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment is routine practice.4,7–9 Additionally, many survivors preserve their independence with good functional capacity and return to work.2,4,9 However, some studies point to poor neurologic outcomes, particularly in diabetic patients.10,11

Although quality of life is subjective, there are tools to measure and compare it, such as the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey and the EuroQoL 5 dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D).2 Systematic reviews and recent studies reveal that most survivors have a ‘good’ or ‘acceptable’ quality of life, but most studies only include patients with a good neurologic outcome.6,12,13 Some of the factors that impact quality of life are age, comorbidity, gender, marital status, cognitive deficits, and emotional problems.1,7,10

In Portugal, data on post-resuscitation outcomes are scarce. Our goal is therefore to explore the situation in this country and to contribute to the improvement of care. This study aims to assess outcomes post-CA such as survival rate and survival time, health-related quality of life (HR-QoL), independence, and performance status of CA survivors.

MethodsSetting, design and patientsThis was a single-center, observational, retrospective study. It took place in Cova da Beira University Hospital Center in Covilhã, which serves an area with a population of 86000.

The first part of our study consisted of analysis of patients’ clinical records, focusing on survival time, independence, and admission to long-term care facilities. For this, we included all adults admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) who suffered CA and had ROSC between January 2015 and December 2019. Ninety-seven patients met all criteria, and nine responded to the questionnaire (Figure 1).

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the hospital's ethics committee and all patients who participated in the questionnaire gave their informed consent.

Data collectionClinical information was collected mainly from the SClínico and Centricity Critical Care Clinisoft software platforms.

QuestionnaireDue to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, six of the patients responded to the questionnaire via phone call, and three responded in person. The survey included the EuroQoL group's EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, a question to compare quality of life before and after CA, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale. The EQ-5D-3L is a generic tool with five questions, each concerning one of five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), and a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). Based on the value set derived for Portugal and the responses, an index that measures HR-QoL was obtained.14–16

For performance status, we used the ECOG scale. Unlike CPC, it conveys not just neurologic performance, but also the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL).4,9,17

Statistical analysisIBM SPSS version 27 was used for the statistical analysis. All statistical tests were interpreted at a 0.05 significance level, although we also considered p-values <0.10 as a tendency for correlation. First, we used descriptive statistics and applied normality tests. According to the normality of distribution, we used the Mann–Whitney U test, the Student's t test, Spearman's test and the one-sample t test. Survival function estimates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. For loss of independence and institutionalization, we performed the McNemar test and two logistic regression models. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data, as appropriate. Cramer's V served as a measure of the relative strength of association with the following criteria for interpretation: <0.1 very weak, 0.1–<0.3 weak; 0.3–0.5 moderate; and ≥0.5 strong.18

ResultsSurvival and independence post-resuscitationPatient baseline characteristicsParticipants’ ages ranged from 39 to 97 years and did not vary significantly between female and male genders (p=0.65) (Table 1).

Population characteristics and baseline comorbidities (n=97).

| Male gender, n (%) | 49 (50.5%) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 75.74 (11.747) |

| Cardiac disease, n (%) | |

| History of acute MI | 19 (19.6%) |

| History of heart failure | 41 (42.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27 (27.8%) |

| Pacemaker | 9 (9.3%) |

| Other arrhythmic disordersa | 12 (12.4%) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) | 33 (34.0%) |

| Neurologic conditions, n (%) | |

| History of stroke | 14 (14.4%) |

| Dementia | 5 (5.2%) |

| Diagnosed with depression, n (%) | 17 (17.5%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |

| Diabetes | 39 (40.2%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 45 (46.4%) |

| Hypertension | 62 (63.9%) |

| At least one of the above | 82 (84.5%) |

MI: myocardial infarction; SD: standard deviation.

Most patients were living in their own homes or with family members previous to CA; only 10 were institutionalized in a long-term care facility. Those previously institutionalized were significantly older than those who were not (83.10 vs. 74.83 years) (p=0.01), and the prevalence of previous stroke was significantly higher (p=0.04; Cramer's V=0.243).

Regarding ADL, 67 patients were described as previously independent in their medical records, which is 69.1% of the whole sample and 72.0% of those with their independence level specified in their medical records. The age difference between those previously independent and previously dependent was not statistically significant (74.40 vs. 78.69 years) (p=0.187). However, the prevalence of history of acute myocardial infarction (p=0.002; Cramer-V=0.338), heart failure (p=0.04; Cramer-V=0.233), and dyslipidemia (p=0.01; Cramer-V=0.287) was significantly higher among those considered dependent for ADL.

The cardiac arrest eventThe data showed that 65 (67.0%) of CAs occurred in-hospital, with the majority taking place in the emergency room (26.8%) or the ICU (19.6%). Of the 32 out-of-hospital cases, the most common locations were patients’ residences (15.5%) and healthcare facilities (6.2%) such as diagnostic and dialysis centers. Six of these 32 were witnessed, the witnesses being a medical student, firefighters, an out-of-hospital emergency response team, and two people of unknown qualifications.

In the medical records, an identifiable cause for the event was found for 73 patients, 45.2% of which had a cardiac origin. Information about rhythm and cause of arrest is summarized in Table 2.

Cardiac arrest rhythm and causes.

| Rhythm | |

| Non-shockable rhythm, n (%) | 67 (69.1%) |

| Pulseless electric activity | 35 (36.1%) |

| Asystole | 29 (29.9%) |

| Unspecified non-shockable rhythm | 3 (3.1%) |

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 11 (11.3%) |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 8 (8.2%) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 (2.1%) |

| Unspecified shockable rhythm | 1 (1.0%) |

| Unknown rhythm | 19 (19.6%) |

| Causea | |

| Cardiac causes, n (%) | |

| Heart failure | 17 (17.5%) |

| Acute MI | 11 (11.3%) |

| Arrythmia | 5 (5.2%) |

| Non-cardiac causes, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 (4.1%) |

| Airway obstruction | 4 (4.1%) |

| Other respiratory cause | 10 (10.3%) |

| Trauma | 4 (4.1%) |

| Distributive shock | 8 (8.2%) |

| Blood loss | 3 (3.1%) |

| Metabolic disturbances | 3 (3.1%) |

| Other cause | 4 (4.1%) |

| Unknown cause | 24 (24.7%) |

MI: myocardial infarction.

Thirty-one (63.3%) of the 49 patients who underwent cranioencephalic computed tomography (CE-CT) within a few days of the CA showed new-onset hypoxic–ischemic injury. However, this finding did not correlate with age, gender, comorbidities, rhythm, site, or cause of CA (p>0.10). Among other forms of neuroprognostication, 13 patients (13.4%) underwent an electroencephalogram (EEG), with a normal EEG reported in one case, slow delta and theta activity in one case, burst suppression in one, low voltage in four (one with no activity/isoelectric EEG), and epileptiform activity in six. Due to inconsistencies in timing and lack of data from EEG and other neuroprognostication tools, we did not explore this topic further.

Eighteen patients (18.6%) evolved to persistent coma with no recovery. Forty-six patients (47.4%) died in the ICU, with half of these deaths occurring within 48 hours of CA. Of the 51 patients discharged from the ICU, records of their Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score were available for 34 at the time of ICU discharge: 24 had a score ≥14, three were intubated with a GCS score of 6T-8T, two had a score of 6 and four had a score of 3.

Twenty patients discharged from the ICU died during the remainder of hospital stay.

Survival to hospital dischargeThere were 31 survivors to hospital discharge, with a mean length of hospital stay of 25.28 days. The overall survival to discharge rate was therefore 32.0%.

The quantitative variables with a significant role in survival to discharge were age and severity scores (Table 3).

Quantitative variables impacting survival to discharge.

| Alive at discharge, mean±SD | Died in-hospital, mean±SD | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APACHE II | 19.85±6.218 | 27.28±8.363 | 3.183–11.681 | 0.001a |

| SAPS II | 50.71±14.062 | 65.23±14.342 | 8.199–20.838 | 0.000a |

| SOFA | 6.94±3.351 | 9.48±4.139 | 0.253–4.827 | 0.030a |

| Age, years | 71.74±13.239 | 77.62±10.568 | – | 0.026b |

CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

The survival to discharge rates for OHCA (34.4%) and IHCA (30.8%) were similar (p=0.82). There was also no correlation with specific comorbidities (p>0.10), gender (p=0.52), or IHCA site (p=0.12). Nevertheless, there was a significantly higher survival rate for OHCA when it occurred at other healthcare facilities (83.3%) (p=0.001; Cramer-V=0.707).

The difference between cause of CA specified as cardiac or non-cardiac was statistically significant, with a higher rate of survival for those with a cardiac cause (47.1% vs. 22.5%) (p=0.03; Cramer-V=0.259). There was also a tendency for better discharge rates in those with initial shockable rhythms (54.5% vs. 26.9%) (p=0.08; Cramer-V=0.209). The only other statistically significant factor for survival to discharge was the presence of hypoxic–ischemic injury among those who had undergone CE-CT (16.1% vs. 70.6%) (p=0.001; Cramer-V=0.512).

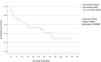

Survival after hospital dischargeAccording to Kaplan-Meier analysis, estimated mean survival was 31.25 months (median 31.60 months, i.e.50% of patients were alive at 31.60 months after CA). The variables with significant impact on the survival curve (Figure 2) were hypertension (p=0.03), new-onset hypoxic–ischemic injury (p=0.03), being in a long-term care facility post-CA (p=0.001), and being dependent for ADL post-CA (p=0.001).

The estimated one-year survival after hospital discharge was 64.3%. If those who died in the hospital are also included, the overall one-year survival was as low as 20.6%. The following variables had a significant impact on one-year survival after discharge: depression (20.0% vs. 73.9%) (p=0.04; Cramer-V=0.431), length of hospital stay (p=0.03), dependence for ADL after CA (40.0% vs. 91.7%) (p=0.01; Cramer-V=0.532), and being in a long-term health care facility after CA (20.0% vs. 88.2%) (p=0.001; Cramer-V=0.682).

Independence after resuscitationDependence and residence status were recorded for 30 of the 31 discharged patients. Comparing their situation before and after CA, 12 (50.0%) of previously independent patients became dependent (p<0.001), and nine (47.4%) of those previously at home were admitted to long-term care facilities (p=0.004). Overall, 40% of those discharged from hospital were independent for ADL and 63.3% were living in their own or a family member's home.

Loss of independence showed a tendency for statistical correlation with age (65.92 vs. 75.17 years) (p=0.09), diabetes (p=0.09; Cramer-V=0.430) and length of hospital stay (p=0.08). These variables were included in a logistic regression model, which showed that those who were previously independent and had diabetes were about 33 times more likely to lose independence compared to those without diabetes (Table 4). It also showed that for each day of hospital stay, there was a 7.7% increase in the probability of loss of independence.

Logistic regression models for loss of independence and admission to long-term care facilities.

| B | Wald test p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of independence after CAa | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.512 | 0.012 | 33.519 | 2.145–523.746 |

| Length of hospital stay, in days | 0.074 | 0.073 | 1.077 | 0.993–1.168 |

| Constant | −2.693 | 0.032 | 0.068 | |

| Admission to long-term care facilities after CAb | ||||

| Female gender | 2.945 | 0.048 | 19.016 | 1.021–354.313 |

| Length of hospital stay, in days | 0.051 | 0.052 | 1.052 | 1.000–1.107 |

| Constant | −4.099 | 0.017 | 0.017 | |

AUC: area under the curve; CA: cardiac arrest; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Regarding residence status, there was a significant correlation between new admissions to long-term care facilities and gender (p=0.04; Cramer-V=0.442), and also length of hospital stay (p=0.002). The logistic regression model (Table 4) showed that females who were previously at home were about 19 times more likely to be admitted to long-term care facilities than males. It also showed that for each day of hospital stay, there was a 5.2% increase in the probability of admission to long-term care facilities.

However, it is important to note that one-year survivors were mostly independent for ADL (65%) and were at home (88%).

Quality of life and performance statusRespondentsThe mean age of respondents was 64.89 years, with no significant differences between genders (p=0.37). All lived in their own home or with family members and were considered independent for ADL. Tables 5 and 6 present further information on their baseline characteristics and CA event.

Respondents’ baseline characteristics.

| Male gender, n (%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 3 (33.3%) |

| Widowed | 2 (22.2%) |

| Married | 4 (44.4%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| 4th year | 4 (44.4%) |

| >4th year | 5 (55.6%) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |

| Previous MI | 1 (11.1%) |

| Chronic heart failure | 3 (33.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (33.3%) |

| Other arrhythmic disorder | 2 (22.2%) |

| Pacemaker | 1 (11.1%) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2 (22.2%) |

| Diagnosed with depression | 1 (11.1%) |

| Diabetes | 2 (22.2%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (33.3%) |

| Hypertension | 2 (22.2%) |

MI: myocardial infarction.

None of the patients had had a stroke or been diagnosed with dementia.

Circumstances of respondents’ cardiac arrest.

| Age at CA, years, mean±SD | 61.44±15.076 |

| Time since CA, years, mean±SD | 3.49±1.367 |

| Site of CA, n (%) | |

| In-hospital | 6 (66.7%) |

| Out-of-hospital | 3 (33.3%) |

| Type of initial rhythm, n (%) | |

| Shockable | 2 (22.2%) |

| Non-shockable | 5 (55.6%) |

| Unknown | 2 (22.2%) |

| Cause, n (%) | |

| Cardiac | 3 (33.3%) |

| Non-cardiac | 4 (44.4%) |

| Unknown | 2 (22.2%) |

CA: cardiac arrest; SD: standard deviation.

Regarding neurologic evaluation post-CA, of the nine respondents, only one had signs of anoxic brain injury on the CT-CE scan, and all had a GCS score of 15 at ICU discharge.

Quality of lifeThe domains with the highest incidence of difficulties were mobility, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The latter two were the most problematic as they had a higher level of perceived severity (level 3 or ‘extreme’), while the domain with the fewest problems reported was self-care (Figure 3).

As shown in Table 7, there was a significant difference between our sample's quality of life index and that of the general Portuguese population, but not compared with the Portuguese population of a similar age range. The mean EQ-VAS was 65.00, which is statistically similar to the Portuguese general population (p=0.24).

EQ-5D index results and comparison with the Portuguese general population, based on Ferreira et al.24

| EQ-5D index, mean±SD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Study sample | Portuguese population | pa | Central Portugal | pa | |

| Overall | 9 | 0.528±0.297 | 0.758 | 0.049 | 0.745 | 0.060 |

| Age >30 years | 9 | 0.528±0.297 | 0.559 | 0.762 | – | – |

| Age group, years | ||||||

| 30–49 | 2 | 0.721±0.065 | 0.824 | – | – | – |

| 50–69 | 3 | 0.673±0.338 | 0.692 | – | – | – |

| ≥70 | 4 | 0.322±0.236 | 0.600 | – | – | – |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 4 | 0.377±0.317 | 0.723b | – | 0.709b | – |

| Male | 5 | 0.649±0.245 | 0.796b | – | 0.788b | – |

Responses to the questionnaire showed that six (66.7%) respondents reported a lower quality of life after compared to before CA.

Performance statusECOG performance status ranged from grade 0 to 2. The most prevalent level of functioning was grade 1 (55.5%), defined as ‘restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature’. Two patients (22.2%) were at grade 0 (“Fully active, able to carry out all pre-disease performance without restriction”). The other two (22.2%) were classified as grade 2, “Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours”. Regarding the patients we were unable to reach, two were in nursing homes and dependent for ADL, according to medical records.

DiscussionComparisons of our results with those of other researchers are inherently difficult due to differences in methodology and sample characteristics.1,2,6,12

Survival to hospital dischargeSurvival to discharge in our study (32.0%) was similar to other studies: 37% in Portuguese studies,19,20 39% in Chen et al.21 and 26.4% in EuReCa TWO.3

Similarly to other studies, age had a significant impact on survival to hospital discharge.8,22 Some point out the possible role of comorbidity in this association; however, Terman et al.23 and Hirlekar et al.8 propose age as an independent factor for these outcomes. Non-shockable rhythm and non-cardiac causes were also associated with a lower survival rate, which is supported by other studies.1,8,19,20 Severity scores have demonstrated a link to survival in other studies as well, but they have also shown some limitations in forecasting patient outcomes.24–26 By contrast, the relation between hypoxic–ischemic brain injury on CE-CT and survival highlighted in our study is supported by resuscitation guidelines, which recommend neuroimaging as a prognostication tool.4 Regarding our finding of a higher survival rate for OHCA when this occurs in other healthcare facilities, a plausible explanation is the greater probability of immediate assistance.

One-year survival and the survival curveStudies on this topic tend to disagree, and this heterogeneity is highlighted in a 2018 meta-analysis on IHCA,27 in which survival to discharge and overall one-year survival indicate a one-year survival of 76% for those discharged alive. Some studies on OHCA report one-year survival of up to 90%.10,28 However, their samples were younger (mean age 61–69 years) and had a higher proportion of cardiac causes and shockable rhythms, which are factors associated with better outcomes.

Loss of independence and admission to long-term care facilitiesOur results appear to contradict the high rates of independence (72.7–91%) and low rates of institutionalization (1–10%) observed in other studies.1,2,4,7 However, these studies refer to six months or more after CA, contrasting with our study, which also included patients with a shorter survival.1,2,4 If these studies are compared to our patients surviving one year or more, the difference begins to fade.

In our sample, diabetes was a major factor in loss of independence. Diabetes has previously been associated with worse functional recovery, worse neurologic outcomes, and lower survival rates.10,11 These links can be attributed to various mechanisms, including the association of diabetes with a larger infarct area, metabolic disturbances, and a higher risk of previous atherosclerosis and thus worse brain perfusion during CA.11 Female gender was also demonstrated to be associated with higher rates of admission to long-term care facilities in our analysis, which is also supported by a previous study.28 The correlation of length of hospital stay with these outcomes has not been explored in other studies, presumably due to the complexity of such analysis.

Quality of lifeFirst and foremost, it should be pointed out that most studies indicate that CA survivors’ quality of life is good or acceptable and similar to the general population, but survivors do report a deterioration of quality of life after CA.2,4,6,12,13,19 As can be seen in the Results section, our study is in agreement with this statement. The quality of life index in our sample differs significantly from that of the sample used for the Portuguese population in Ferreira et al.15 only if we ignore the 20-year gap between the two. When younger age groups are excluded from Ferreira et al.’s sample,15 the difference in the mean EQ-5D scores is not statistically significant. Moreover, when our sample is compared to the overall population of Central Portugal, there is only a tendency for statistical significance, even though it also includes younger people. Overall, it is fair to believe that quality of life may not be significantly different between long-term CA survivors and the age-matched Portuguese population.

Secondly, many studies agree on the high prevalence of problems related to anxiety and depression.1,2,4,6,7 However, there is considerable variability in these studies’ samples and time since CA, making comparisons difficult. An Australian study29 that applied the EQ-5D-3L to 697 patients 12 months after CA had similar results to our study. Examples of very different results are the studies by Granja et al.19 and Bohm et al.13 Specifically in our sample, the most problematic domains overlapped with those of the general population, according to Ferreira et al.15

Unfortunately, our sample was too small to analyze which variables influenced quality of life and performance status.

Performance statusIn previous studies, the cut-off for a good functional capacity/performance status has tended to include those who are capable of some work activity and are independent in ADL.1,9 Taking this into account, we can say that 78% of our respondents had a good performance status, since they maintained their ability to do at least sedentary work (ECOG ≥1). Furthermore, all respondents were capable of self-care and were out of bed for the majority of the day. All in all, similarly to other studies, performance status was satisfactory.2,9

Nevertheless, the patients we were unable to reach should not be forgotten. Consequently, the proportion of good performance status among those alive at the time of this study may go down to 64%.

Study limitations and future considerationsDue to its retrospective nature, our study was unable to provide detailed information about the post-CA period. Another limitation was the sample size, especially for the second section, which impeded analysis of the correlation between quality of life/performance status and other variables (e.g. site of CA and initial rhythm). Furthermore, there was considerable heterogeneity in medical records. For instance, it was not possible to include time until initiation of CPR or time until ROSC in the analysis due to the inconsistency in the way it was reported (some reports were in minutes, while others only had the number of CPR cycles or the number of shocks). Taking all this into account, it would be beneficial to have a prospective study that extended to other medical centers.

In clinical practice, we need to know our patients’ needs in order to guide rehabilitation plans, so it is paramount to continue investigation and to stress the importance of close follow-up of these patients. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation recommends recording of survival and modified Rankin Scale at discharge and at 30 days, as well as quality of life at six and 12 months. Data on other specific problems should also be collected, such as fatigue, anxiety, and participation in society.5 Another useful tool that can be used for functional recovery is the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale.

ConclusionsSurvival to hospital discharge was similar to previous studies. However, it should be stressed that there were significant loss of independence and new admissions to long-term care facilities among these patients. Diabetes, age, and female gender were important factors in these outcomes. One year after CA, only 20 (20.6%) patients were alive, and only 13 (13.4%) were independent in ADL. Regarding quality of life, the EQ-5D index and the most problematic domains (pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) were similar to the Portuguese general population. However, it should be borne in mind that there was a perceived decline in quality of life. Additionally, most respondents had a good performance status, but only two (22.2%) were fully active without restriction. Overall, these findings highlight the need to improve the care and follow-up of these patients.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We acknowledge all the help provided by the administrative and medical staff of Cova da Beira University Hospital Center. We also thank Célia Nunes, PhD, from the University of Beira Interior, who helped us review the statistical analysis.