The European Society of Cardiology guidelines on cardiomyopathies advocate for a comprehensive diagnostic strategy, integrating extracardiac assessments and tailored genetic tests. Although inherited metabolic diseases are rare, more than 40 metabolic disorders with cardiac involvement have been described.

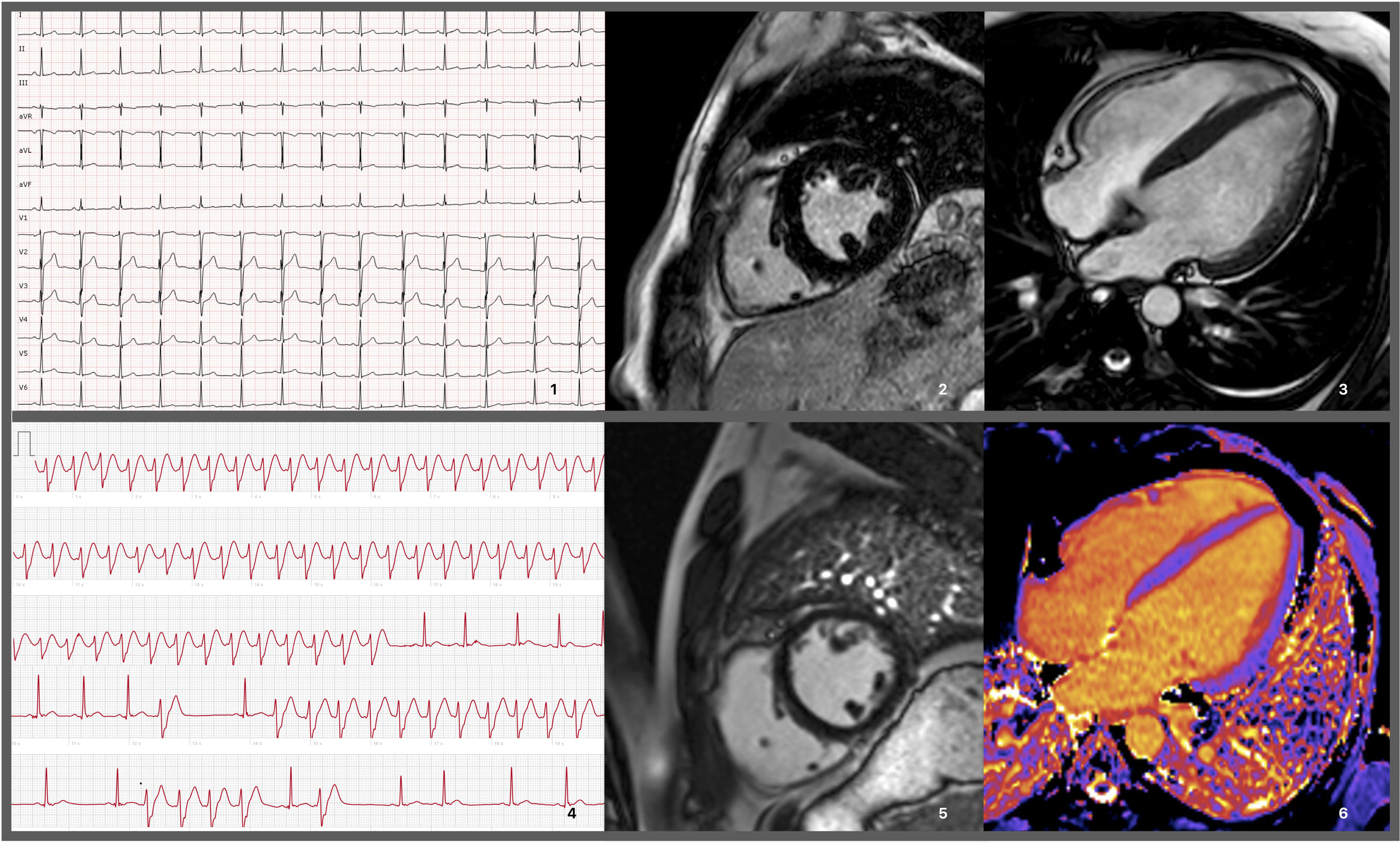

A 25-year-old male with no significant medical or family history presented with fever, tonsillitis, and rapidly progressing dyspnea, leading to respiratory failure and intubation. Initial tests showed elevated creatinine kinase (CK) levels (1200 U/L, normal <189 U/L) and myoglobinuria, requiring transitional renal replacement therapy. Echocardiogram revealed moderately reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF 45%). Myocarditis was suspected, but cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed 10 days later showed LVEF recovery and mild hypertrophy (13 mm), without edema or fibrosis; serum troponin T was only mildly increased (peak 70 ng/L, N <14 ng/L) (Figure 1). The episode was attributed to a systemic viral syndrome with multiorgan involvement.

Electrocardiograms and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging exams performed on the patient. 1: EKG performed prior to hospitalization discharge showing no remarkable findings other than an rSr’ pattern in lead DIII. 2 and 3: MRI prior to hospitalization discharge revealing slight concentric hypertrophy, without enhancement. 4: Recording of a wide QRS tachycardia, raising the hypothesis/possibility of a non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. 5 and 6: MRI during follow-up, showing absence of LGE and normal native T1 mapping values (considering the reference values for the sequence and local MRI laboratory).

The patient remained stable with normal LVEF over three years and was discharged. However, at age 30, he returned with palpitations and brief tachycardia episodes were detected by his smartwatch. An MRI during follow-up revealed a decrease in left ventricular wall thickness and right ventricular dilation compared to the previous MRI, without late gadolinium enhancement and normal T1 mapping (Figure 1).

A 24-hour Holter monitor and electrophysiological study found no events. The genetic panel for 71 cardiomyopathy-related genes was negative. Laboratory tests revealed mildly elevated CK levels (327 U/L) without recent physical activity and normal NTProBNP levels. Serial measurements showed fluctuating CK levels despite reporting a consistently sedentary lifestyle. He reported exercise intolerance since childhood, with mild muscle pain that worsened with fasting and improved with carbohydrate intake, and tachycardia associated with an intermittent fasting diet.

Neuromuscular evaluation showed isolated calf hypertrophy, negative myositis antibodies, an electromyogram with polyphasic motor unit potentials, and elevated acylcarnitine levels (C16 and C18), indicative of a mitochondrial fatty acid catabolism disorder. Finally, genetic testing identified the pathogenic variant NM_000098.2 (CPT2) p.(Ser113Leu) in homozygosity, confirming hereditary carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency. Despite dietary and activity recommendations, the patient admitted continuing the intermittent fasting regimen for weight loss and the six-month follow-up echocardiogram showed persistent mild ventricular dysfunction (LVEF 46%).

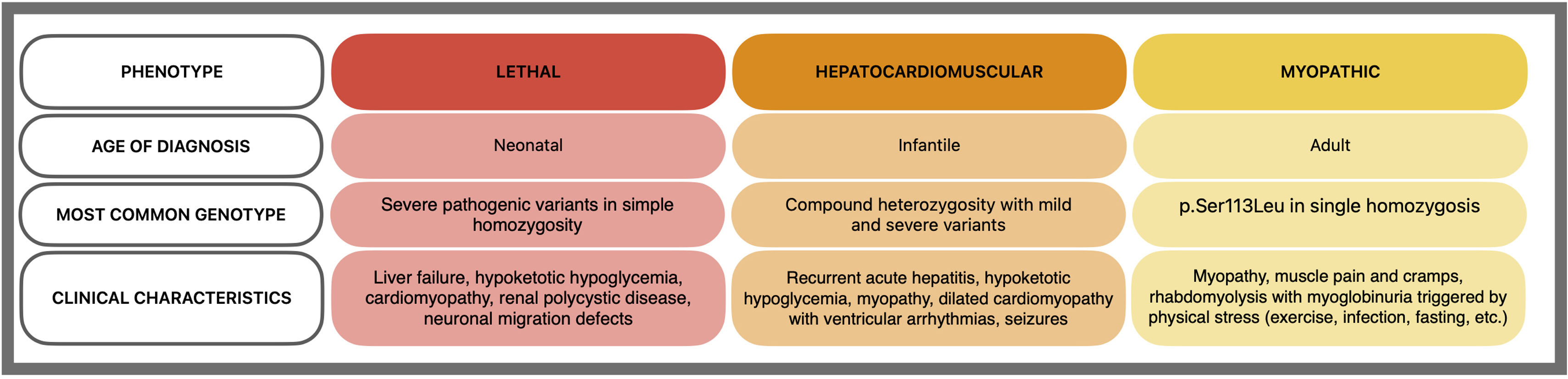

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency, the most common long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorder, is caused by biallelic variants in the CPT2 gene.1 It has three phenotypes with a strong genotype–phenotype correlation2 (Figure 2):

- 1.

Lethal neonatal: severe symptoms at birth, including hypoglycemia, hypoketosis, and severe liver and muscle disease.

- 2.

Infantile hepatocardiomuscular: appears in infancy with hepatitis, hypoketotic hypoglycemia, and seizures, potentially involving the heart.

- 3.

Classic myopathic: recurrent myalgia, weakness, and myoglobinuria triggered by exercise, fasting, or fever in adulthood. Recent evidence suggests possible myocardial involvement,3 and the p.(Ser113Leu) variant is the most common.

Specific management strategies include implementing a carbohydrate-rich and low-fat diet and avoiding potential triggers. Emerging evidence linking the classic myopathic form with cardiomyopathy underscores the need for accurate diagnosis in order to stablish preventive measures, which can significantly impact patient outcomes.4,5

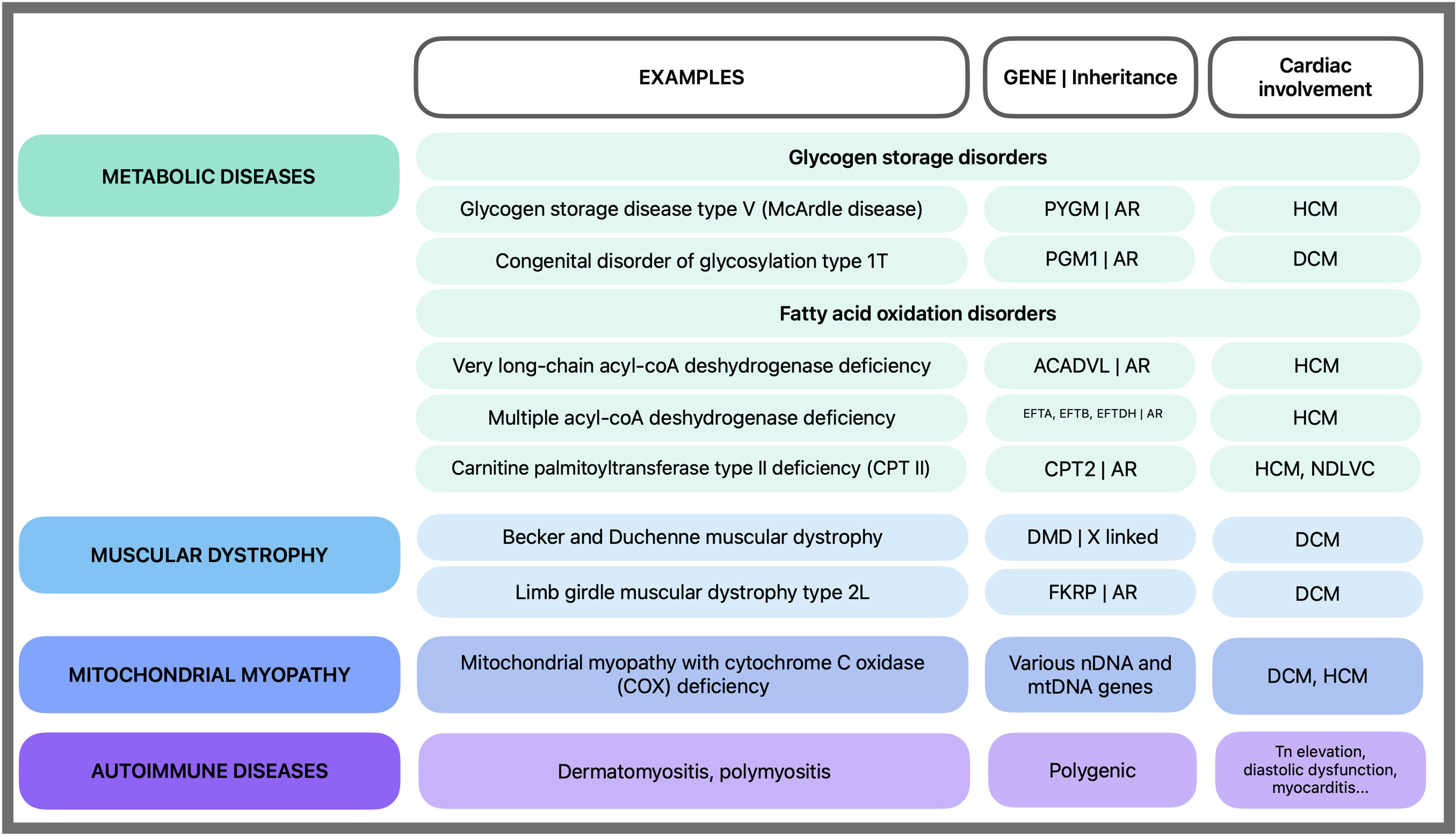

Hereditary CPT II deficiency should be suspected in patients with systolic dysfunction concomitant rhabdomyolysis and exercise intolerance (Figure 3).

Non-acquired causes of rhabdomyolysis with cardiomyopathy. Rhabdomyolysis is more common in genetic metabolic diseases and less common in other conditions. AR: autosomal recessive; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; nDNA: nuclear DNA; NDLVC: non-dilated left ventricle cardiomyopathy; Tn: troponin.

Lorena Herrador and Fernando de Frutos participated in the patient's cardiological and neurological assessment, gathered medical history, reviewed diagnostic tests and imaging studies, and contributed to the diagnosis and treatment plan. Elena García Arumi carried out the molecular genetic studies. All authors contributed to the revision of the case report and approved the final version for submission.

Statement of consentConsent for publication was obtained from the patient in line with the COPE best practice guidelines. Publication was approved by local ethics committee (PR176/24).

FundingNo funding was provided for this case report.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the content of this manuscript.

We are grateful to CERCA/Generalitat de Catalunya for the institutional support. We would like to thank Velina Nedkova, Carles Diez-Lopes and Jose Gonzalez-Costello from Bellvitge University Hospital for their support with this case.