The overall topic of the work presented by Mendes et al.1 in this issue of the Portuguese Journal of Cardiology hinges on hypertension (HTN) monitoring. Many unsuspecting readers of the aforementioned article may not be aware that this theme – primary HTN monitoring – is a controversial and debatable issue, even outside the recognizable boundaries of the COVID pandemic. The “Proof-of-Concept” for the difficulties in assessing arterial blood pressure is the need for specific and concise guidelines2 on the subject.

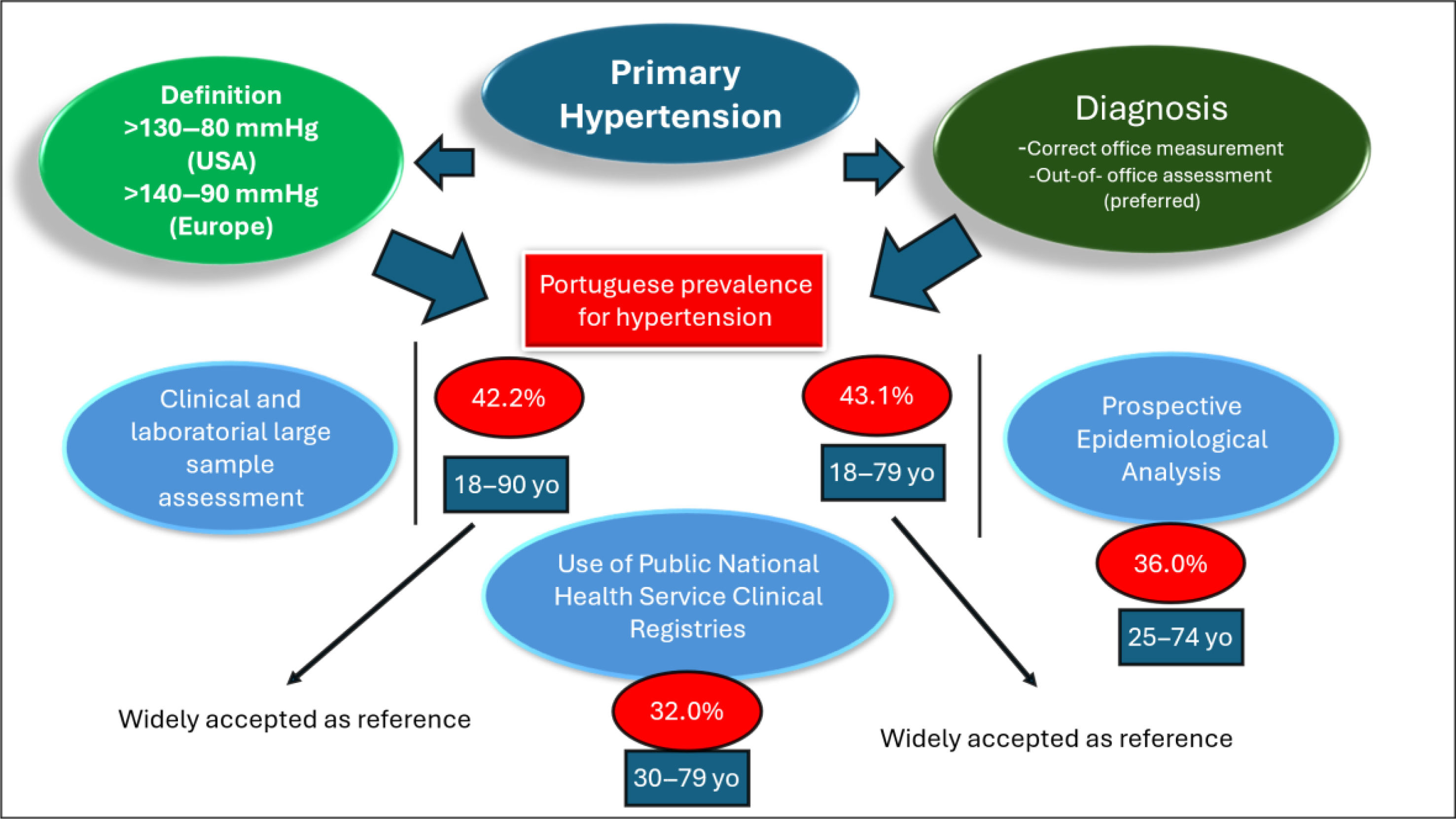

Indeed, for those less entangled in the HTN world, this most common of all risk factors seems a simple issue, with an often (deemed) simplistic diagnosis and classification. However, nothing is further from the truth. To demonstrate this, it is important for the reader to know that the classification of hypertension (HTN) remains highly contested in Europe, with two opposing guidelines having been issued recently. Elsewhere in the world,3 the same conflicting evidence holds true, with the adoption of a threshold of 130–80 mmHg for the diagnosis of hypertension4 in the US guidelines, which is clinically and epidemiologically controversial, prompting very important criticisms stemming from the very same country.5

In Mendes et al.’s work, the complexity and putative criticism – about HTN monitoring – gain a different layer of complexity, since the data, on morbidity and mortality, collected during the pandemic is hard to verify – in failing health systems, everywhere, overloaded by the consequences of the infection,6 with diagnostic entities poorly reflected in official mortality and morbidity registries.7 Moreover, the use of public registries – presented in their work is also debatable. For example, the reputed “BI-CSP” (primary care data from all the primary care units in Portugal) has become a fashionable source of information, due to its unrestricted access. This data base has been used for the study of HTN8 and other common risk factors like diabetes mellitus9,10 and is open to cautious analysis.11,12 The main reason for these cautious reserves is the fact that the Portuguese family health units are rewarded for best results (namely in the therapeutic control of HTN), so some doubt the absolute scientific absolute validity for this data.11 The same is true relative to diabetes in “BI-CSP”.10

To fully understand the validity of the work presented one should have a notion of the expected prevalence of HTN in Portugal. The general media reports around 40% of essential HTN,13 in the Portuguese adult population. There have been, indeed, two papers14,15 stating prevalences around 40%. Of course, there were other publications with different methodologies – namely a different age set for the population studied, depicting different results,16 stating a much lower overall prevalence for HTN, of only 36%. Finally, the reported international prevalence for HTN, in Portugal (WHO report, 2023) is set at 32%.17 We believe the WHO report is based on public records, using a different age gap. Thus, methodology is key in assessing such common risk factors and fundamental in judging the published work (see Figure 1).

The methodology in the work by Mendes et al. is subjected to some general critique. The inclusion of an age criteria under 65 years of age limits the validity of this work. The authors present this fact as a limitation of the paper, since the referred public data does not offer information over that age limit. In fact, it is known that the highest mortality rate attributed to SARS COV 2 infection occurred in individuals aged >65 years, so extrapolating morbidity and mortality from the elderly, using the <65 years threshold may not be adequate. In addition, the prevalence of HTN is admittedly higher in >65 years of age. On the same note, older adults’ adherence to therapy is often lower – due to frequent multiple medications – which increases the risk of complications from uncontrolled hypertension.

Another source of potential critics is the cutoff for “control” of blood pressure at <150/90 mmHg. This seems strange to the general clinician, since, despite all guideline disputes, 140/90 mmHg is still the accepted threshold for HTN in Portugal and in Europe. Again, the authors state the public health registry as the source of this awkward “controlled” notion presented in the text.

As for the mathematic model itself, it seems correct, but it is beyond the reach of the common clinician and different from the usual statistic treatments presented by epidemiologic studies. Nevertheless, we do accept that the authors are affiliated with various institutions, including a scientific center recognized for its work in mathematics and applications, within the health sector.

The conclusion is as expected: the pandemic hindered medical services, prompting uncontrolled HTN and, consequently, HTN related mortality. So, without committing to a specific HTN prevalence, the authors state a 26.4% relative reduction in the number of HTN patients registered, due to failing health services, and a 21.8% relative reduction of the registered patients with <150/90 mmHg. These results, of course, will increase the model's calculated mortality (176 additional deaths) and a 3287 increase in years-of-life-lost (YLL), between March 2020 and February 2022.

However, we, the careful readers of this mathematical paper, feel that another message can be drawn from the published results and conclusions. We, the clinicians in the front line, believe that the vast resources used to curb the COVID pandemic could be replicated to curb this other silent and likewise deadly pandemic, the HTN pandemic.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.