Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is caused by the obstruction of the main pulmonary artery due to thrombosis and vascular remodeling. Regarding the need for anticoagulant therapy in CTEPH patients, this study aimed to compare rivaroxaban with warfarin in terms of its efficacy and safety in patients undergoing endarterectomy surgery.

MethodsThe study was a parallel clinical trial in patients who underwent endarterectomy following CTEPH. A total of 96 patients were randomly selected and assigned to two groups: warfarin-treated (control) and rivaroxaban-treated (intervention). Patients were clinically assessed for re-thrombosis, re-admission, bleeding, and mortality in the first, third, and sixth months after surgery.

ResultsThere was no significant difference in the occurrence of thrombosis between the two groups within the first, third-, and sixth-months post-surgery (p=0.52, 1, 0.38 respectively). Moreover, the mortality rate (p=0.9), bleeding rate (p=0.06), and re-admission rate (p=0.15) showed no significant differences between the two groups.

ConclusionRivaroxaban may be as effective as warfarin in treating CTEPH patients after endarterectomy in the short term and can be used as an anticoagulant in these patients. However, studies with long-term follow-ups are needed to consolidate the strategy of treating these patients with rivaroxaban.

A hipertensão pulmonar tromboembólica crónica (HPTEC) é causada pela obstrução da artéria pulmonar principal devido a trombose e a remodelagem vascular. Relativamente à terapêutica anticoagulante em doentes com HPTEC, este estudo teve como objetivo comparar o rivaroxabano com a varfarina no que concerne à sua eficácia e segurança em doentes submetidos a cirurgia de endarterectomia.

MétodosO estudo consistiu num ensaio clínico paralelo em doentes submetidos a endarterectomia após HPTEC. Foram selecionados aleatoriamente 96 doentes e distribuídos por dois grupos: doentes tratados com varfarina (controlo) e doentes tratados com rivaroxabano (intervenção). Os doentes foram avaliados clinicamente para retrombose, reinternamento, hemorragia e mortalidade, ao primeiro, terceiro e sexto meses após a cirurgia.

ResultadosNão se registaram diferenças significativas em relação à ocorrência de trombose entre os dois grupos após a cirurgia. (Valor p=0,52, 1, 0,38 respetivamente). Além disso, a taxa de mortalidade (Valor p=0,9), a taxa de hemorragia (Valor p=0,06) e a taxa de reinternamento (Valor p=0,15) não revelaram diferenças significativas entre os dois grupos.

ConclusãoO rivaroxabano pode ser tão eficaz a curto prazo como a varfarina no tratamento de doentes com HPTEC após endarterectomia e pode ser utilizado como anticoagulante nestes doentes. No entanto, são necessários estudos de seguimentos a longo prazo para consolidar esta estratégia de tratamento com rivaroxabano.

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is caused by the obstruction of the main pulmonary artery due to thrombosis-related issues and vascular remodeling.1 CTEPH is classified as the fourth category of pulmonary pressure classification in which the average pulmonary artery pressure is equal to or greater than 20 mmHg.2

The incidence of CTEPH in the United States is estimated at 5000 new cases per year. However, this is likely an underestimation, as CTEPH is not always correctly diagnosed.3 The disease causes an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, a progressive rise in pulmonary pressure, and, eventually, right heart failure, leading to death if not appropriately treated.4

Endarterectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with CTEPH.5 All CTEPH patients should receive anticoagulant therapy after diagnosis, and this therapy must be maintained lifelong, even after endarterectomy surgery.6 Anticoagulant therapy aims to prevent the recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and thrombosis in the pulmonary arteries.6

Warfarin is an accepted anticoagulant and is routinely used as a treatment for CTEPH or after endarterectomy surgery. However, patient adherence to its administration may be low due to the challenges of taking warfarin, including dosing according to the international normalized ratio (INR), extensive interactions with drugs and food, and routine INR monitoring.

Several studies have appraised the efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in CTEPH and have achieved promising results.7,8 However, very few randomized controlled clinical trials have assessed the safety and effectiveness of these agents in patients undergoing endarterectomy.

Considering the advantages of treatment with rivaroxaban compared to warfarin – including no need for monitoring and fewer drug interactions – this study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in comparison with warfarin in patients who underwent endarterectomy due to thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Materials and methodsEthicsThe study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (ethics code number IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1398.175) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20151227025726N22). Written informed consent form was collected from all patients.

Study populationThe study was a randomized clinical trial conducted at Dr. Masih Daneshvari Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Patients who underwent endarterectomy following CTEPH diagnosis were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: refusal to sign the consent form, history of an allergic reaction to warfarin or rivaroxaban, any active bleeding or history of massive bleeding within three weeks of admission, cerebral aneurysm, dissection of the aorta, history of spinal puncture, and blood dyscrasia, uncontrolled systolic blood pressure (≥180 mmHg), inflammation and effusion of the pericardium and infective endocarditis, pregnancy and lactation, liver failure (Child-Pugh stages C and D), renal failure (GFR <30 ml/min), and co-administration with potent CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inducers or inhibitors.

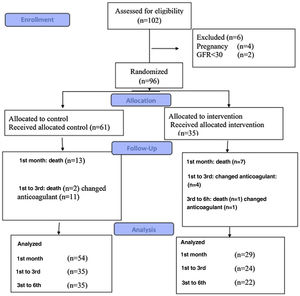

InterventionsIn total, 96 patients were included in the study: 61 patients (the control group) received warfarin, and the other 35 (the intervention group) received rivaroxaban (Figure 1). The blocking method was adopted for randomization.

All patients received warfarin before surgery, which was discontinued five days before endarterectomy. Patients received enoxaparin three days before the surgery as bridge therapy with a dosing regimen of 1 mg/kg every 12 hours; this treatment was discontinued 24 hours before surgery. After undergoing surgery, patients were randomly assigned to the warfarin or rivaroxaban group.

Patients in the warfarin group continued taking warfarin (Orion pharma) 24 hours after the surgery based on the INR goal of 2–3. Patients in the rivaroxaban group received rivaroxaban (Xalerban®) at a dose of 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, followed by 20 mg once daily. The rivaroxaban dose was adjusted according to their renal function calculated via the Cockroft-Gault equation. All other therapeutic regimens were the same in both groups.

The demographic data of the patients and their histories of comorbidities were recorded for both groups.

OutcomesThe primary outcome was the recurrence of thrombosis, which was evaluated and recorded within the first, third, and sixth months of surgery. Thrombosis recurrence was defined as the occurrence of deep vein thrombosis as confirmed by ultrasonography or pulmonary embolism via computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiography scans.

The secondary outcomes were the bleeding rate (including major and minor bleeding), hospital re-admissions due to any cause, and mortality rate. Bleeding events were defined based on the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis's criteria.9 Major bleeding was defined as follows: a reduction in hemoglobin levels to >2.0 g/dL, any bleeding event that needs more than 2 U of blood transfusion, and bleeding from any vital organs (including the brain). Minor bleeding was considered any temporary, non-life-threatening bleeding of other organs. HAS-BLED scores were calculated to assess the one-year risk of bleeding in patients under anticoagulant therapy. These data were also recorded on the first, third, and sixth months after surgery at the cardiology clinic of Dr. Masih Daneshvari Hospital based on weekly phone follow-ups. CT angiography of the chest was also performed in the first, third, and sixth months after surgery. Patients who died near the end of the follow-up deadline were included in the data analysis.

Sample size and statistical analysisGpower software was used to determine the sample size. Due to the physicians’ preference for warfarin administration and availability of specific antidotes in case of bleeding with warfarin, the sample size ratio for the warfarin group to the rivaroxaban group was considered 2:1. Assuming the first type of error equals 0.05 with 80% power and considering the possible loss of samples, 61 patients in the warfarin group and 35 patients in the rivaroxaban group were selected.

The results were analyzed using SPSS v.25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was performed to evaluate the differences for binary variables. Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to assess the normality of data distribution. To compare the differences in numeric variables, the Student-t or Mann-Whitney U test was carried out.

ResultsThe demographic data and medical history of the patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of their age, gender, body mass index, and past medical history. However, a history of pre-thrombosis was significantly lower in the rivaroxaban group.

Information on age, gender, body mass index, and past medical history of the study population.

| Variable | Warfarin group(N=61) | Rivaroxaban group(N=35) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 47.2±13.2 | 43.2±12.9 | 0.15 |

| Sex (male) | 32 (52.4%) | 21 (60%) | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 (23.2–30) | 27 (23.9–31.2) | 0.18 |

| Diabetes | 10 (16.3%) | 5 (14.28%) | 0.78 |

| Hypertension | 17 (27.86%) | 9 (25.71%) | 0.81 |

| IVC filter | 4 (6.5%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 10 (16.3%) | 5 (14.2%) | 0.78 |

| Smoking history | 21 (34.4%) | 14 (40%) | 0.05 |

| Malignancy | 2 (3.2%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 |

| APS | 8 (13.1%) | 5 (14.2%) | 0.87 |

| IBD | 3 (4.9) | 1 (2.8) | 1 |

| SLE | 12 (19.6%) | 3 (8.5%) | 0.24 |

| PUD | 13 (21.3%) | 9 (25.7%) | 0.62 |

| Seizure history | 7 (11.4%) | 2 (5.7%) | 0.47 |

| Depression | 4 (6.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.29 |

| COPD | 12 (19.6%) | 8 (22.8%) | 0.71 |

| Anemia | 27 (44.2%) | 22 (62.8%) | 0.07 |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (9.8%) | 2 (5.7%) | 0.7 |

| Splenectomy | 2 (3.2%) | 3 (8.5%) | 1 |

| Chronic osteomyelitis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| Pacemaker use | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 |

| HF (FC 3 and 4) | 54 (88.5%) | 30 (85.7%) | 0.68 |

| Pre-thrombosis | 23 (37.7%) | 6 (17.1%) | 0.03 |

| Pre-bleeding | 5 (8.1%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 |

| HAS-BLED score(within three days of surgery) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.35 |

Data are presented as mean±SD in percentages. APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FC: functional class; HF: heart failure; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IVC: inferior vena cava; PUD; peptic ulcer disease; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

The results of thrombosis, bleeding, re-admission, and mortality within the first, third, and sixth months of surgery are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding these parameters. Moreover, when we controlled the pre-thrombosis variable as a potential confounding factor, the significance was not affected.

Results for thrombosis, re-admission, bleeding, and mortality between the two groups.

| Variable | Warfarin | Total | Rivaroxaban | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombosis within the first month | 9 (16.6%) | 54 (100%) | 3 (10.3%) | 29 (100%) | 0.52 |

| Thrombosis from the first to the third months | 1 (2.85%) | 35 (100%) | 1 (4.16%) | 24 (100%) | 1 |

| Thrombosis from the third to the sixth months | 5 (14.2%) | 35 (100%) | 1 (4.5%) | 22 (100%) | 0.38 |

| Hospitalization within the first month | 28 (51.8%) | 54 (100%) | 9 (31%) | 29 (100%) | 0.06 |

| Hospitalization from the first to the third months | 6 (17.1%) | 35 (100%) | 3 (12.5%) | 24 (100%) | 0.72 |

| Hospitalization from the third to the sixth months | 11 (31.4%) | 35 (100%) | 4 (18.8%) | 22 (100%) | 0.36 |

| Bleeding within the first month | 9 (16.6%)Major=1Minor=8 | 54 (100%) | 1 (3.4%)Minor=1 | 29 (100%) | 0.15 |

| Bleeding from the first to the third months | 2 (5.7%)Minor=2 | 35 (100%) | 1 (4.1%)Minor=1 | 24 (100%) | 1 |

| Bleeding from the third to the sixth months | 2 (5.7%)Minor=2 | 35 (100%) | 1 (4.5%)Major=1 | 22 (100%) | 1 |

| Mortality within the first month | 13 (22.8%) | 57 (100%) | 7 (22.5%) | 31 (100%) | 0.9 |

| Mortality from the first to the third months | 2 (4.5%) | 44 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (100%) | 0.53 |

| Mortality from the third to the sixth months | 1 (2.3%) | 42 (100%) | 1 (4.1%) | 24 (100%) | 1 |

Data are presented as percentages.

The results for pulmonary artery pressure are given in Table 3. As can be seen, there were no significant differences between the two groups in this parameter.

The present study showed that rivaroxaban had similar efficacy and safety as warfarin in treating CTEPH in patients undergoing endarterectomy. Hence, rivaroxaban may be considered as a reasonable alternative for warfarin in these patients.

Considering the lower rate of pre-thrombosis in the rivaroxaban group, we controlled for this variable. A subsequent re-evaluation of the between-group differences showed that the significance levels of these differences were not affected.

The present results are consistent with those of a study conducted by Gavilanes-Oleas et al., who found that DOACs were safe and effective for CTEPH patients.7 However, that study was conducted with CTEPH patients who were both candidates and non-candidates for endarterectomy. Another point to consider is that our study was a clinical trial, whereas the mentioned research was a cohort study.

Another study by Senna et al. examined 501 patients with CTEPH from September 2011 to April 2018. The results showed that DOACs were safe and effective in patients with CTEPH.10 They also had a similar risk of thrombosis to warfarin, which is in line with our results. However, that experiment was a retrospective observational study in which confounding by indication should be considered.

Our study did not show any significant differences between the two groups in terms of bleeding, re-admission, and mortality, indicating that rivaroxaban might be a promising anticoagulant for CTEPH patients undergoing endarterectomy. Its ease of administration, lack of a need for monitoring, and lower drug interactions makes it more convenient than warfarin.

Huang et al. compared rivaroxaban's and warfarin's safety and effectiveness in pulmonary embolism (PE) patients. It was concluded that both drugs had the same efficacy and safety.11 Frank et al. showed the same results in PE patients; they also demonstrated that the cost of treatment and hospital-related complications were lower for rivaroxaban.12

In a retrospective study, Bunclark et al. concluded that the bleeding rates were similar in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants (DOACS) and those receiving warfarin. However, the recurrence of VTE was higher in patients treated with DOACS. These results are inconsistent with ours, perhaps due to differences in methodologies.13

Several other studies have shown that PE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) patients treated with rivaroxaban stay in the hospital for shorter periods than those treated with warfarin.14,15 The length of hospital stays was not evaluated in our study. Instead, we evaluated the re-admission rates, which were not statistically significant between the two groups.

Most studies conducted to compare the safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban and warfarin have been conducted on PE and DVT patients. Clinical trials evaluating rivaroxaban's non-inferiority compared to warfarin in CTEPH patients undergoing endarterectomy are still lacking. Thus, the present study makes a significant contribution to the literature.

The main limitation of our study was the inequality of the number of patients in each of the two groups. Due to the physician's preference for prescribing warfarin and the availability of specific antidotes, we utilized a 2:1 allocation ratio. Also, the high mortality rates in both groups made it difficult to interpret the results on the third and sixth months after surgery, as the sample sizes at these months were low. It is noteworthy that the mortality rate was not related to cardiovascular diseases alone, and we considered all causes of mortality in our study. Furthermore, our study included COPD patients who underwent surgery, and COPD is a risk factor for poor outcomes after endarterectomy. Our sample also included cancer patients and patients with severe heart diseases, which are additional risk factors for poor prognosis.16

It is suggested that future studies examine outcomes over longer periods. The lengths of hospital stays should also be compared between the two groups in future research. Conducting a non-inferiority trial is also suggested to determine whether rivaroxaban is non-inferior to warfarin in patients undergoing endarterectomy.

ConclusionRivaroxaban appeared to be as effective as warfarin when administered to treat CTEPH patients undergoing endarterectomy in the short term. However, studies with long-term follow-ups are needed to consolidate the strategy of treating these patients with rivaroxaban.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.