Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is an antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated systemic vasculitis and is characterized by inflammation of blood vessels. The aim of the present study was to assess cardiac valvular changes in patients with GPA in a cohort of 105 patients followed for a mean of six years.

MethodsWe followed 105 patients (mean age 50.4 years, 67 female) for a mean of 6.2±1.3 years. Echocardiography and laboratory tests were performed in all patients.

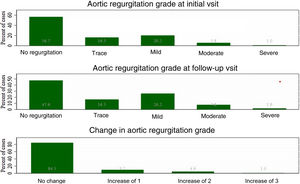

ResultsAt baseline, 43% of patients were diagnosed with aortic regurgitation (AR), which was the most common valvular lesion. Moreover, it was the only valvular involvement that significantly increased during observation (p=0.01). In a multivariate model, only D-dimer level was a predictor of AR in this group of patients (OR 8.0 (95% CI: 1.7–38.2, p=0.01).

ConclusionsInvolvement of the heart valves is a common finding in patients with GPA, but significant valvular disease is a rare complication. The most common valvular disease in this group of patients is AR. Aortic valves are also the most prone to degeneration in the course of the vasculitis.

Granulomatose com poliangeíte (GPA) é uma das vasculites sistémicas associadas a anticorpos anticitoplasma de neutrófilos (ANCA) e é caracterizada por inflamação dos vasos sanguíneos. O objetivo do presente estudo foi avaliar as alterações valvulares cardíacas em pacientes com granulomatose com poliangeíte em uma coorte de 105 pacientes acompanhados em média durante seis anos.

MétodosAcompanhámos 105 pacientes (idade média de 50,4 anos, 67 mulheres) em média durante 6,2±1,3 anos. Foram realizados ecocardiografia e exames laboratoriais em todos os pacientes.

ResultadosNo início do estudo, 43% dos pacientes foram diagnosticados com insuficiência aórtica, sendo a lesão valvular mais comum. Além disso, foi o único envolvimento valvular que aumentou significativamente durante a observação (p=0,01). Num modelo multivariado, apenas a concentração de dímero D foi um preditor de insuficiência aórtica nesse grupo de pacientes (OR=8,0, IC 95%: 1,7–38,2, p=0,01).

ConclusõesO envolvimento das válvulas cardíacas é um achado comum em pacientes com granulomatose com poliangeíte, mas a doença valvular significativa é uma complicação rara. A doença valvular mais comum nesse grupo de pacientes é a regurgitação aórtica. As válvulas aórticas também são as mais propensas a degeneração no curso da vasculite.

The primary systemic vasculitides are heterogeneous, multisystem disorders. Their etiology is unknown. The most common subgroup is antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV). There are three types of AAV: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).1,2 GPA is the most common type of AAV and is defined by the presence of ANCAs targeting specific antigens, particularly proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA) and myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA). It is characterized by granulomatous inflammation of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, both veins and arteries. The inflammatory processes in GPA mainly affect the ear, nose, throat, lower respiratory tract and kidneys, but any organs and systems may be involved, including the cardiovascular system.2

Cardiac involvement in GPA is reported in approximately 6–44% of cases.3–5 The two most common cardiac manifestations in the acute phase of the disease are pericarditis and coronary arteritis, which account for almost 50% of cases; other cardiac complications include myocarditis, conduction disturbances and endocarditis.6,7 An increased incidence of various cardiovascular events has been found among GPA patients during the disease's course.8,9 Cardiac valve involvement is a rare complication of GPA, most commonly manifested by aortic regurgitation (AR). Most data on this complication are limited to case reports and retrospective studies10–13 and there are no prospective observational studies assessing the progression of valvular disease in the course of GPA.

ObjectivesThe aim of this study was to analyze cardiac valvular involvement in patients with GPA in a cohort of 105 patients followed for a mean of six years.

MethodsIn this prospective observational study, 114 consecutive GPA patients who were hospitalized in the Department of Family Medicine, Internal and Metabolic Diseases at the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland, between February 2010 and November 2020 were included. All patients were classified as having GPA, according to the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference criteria for AAV.2 Consecutive GPA patients were included in the study when a new diagnosis of AAV was established. All patients received initial treatment and were followed up at our center. Disease activity was scored using version 3 of the validated Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS), on which a BVAS of <1 defined remission.14 Data collection included medical history, physical examination, laboratory studies, echocardiographic examination and review of all cardiovascular adverse events during observation.

Ethical issuesThe study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Warsaw (approval no. AKBE/130) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Laboratory parametersBlood samples were collected as soon as possible after inclusion into the study during the active phase of the disease and again when the patients were in stable remission. Laboratory parameters were calculated by the Central Laboratory Department in our hospital. All patients were tested for ANCAs by indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Echocardiographic parametersIn all patients, echocardiographic examinations were performed in the acute phase and then repeated every six months during follow-up. M-mode and two-dimensional standard echocardiography (Mindray M7, Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Shenzhen, China) followed by pulsed and continuous-wave Doppler recordings and tissue Doppler were performed by an experienced cardiologist. Five consecutive measurements were averaged for each parameter. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was obtained using the biplane Simpson method. Multiple qualitative, semi-quantitative, and quantitative measurements were used to grade AR (grade: no AR, trace, mild, moderate, or severe).15

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are summarized as means and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range. Qualitative variables are presented as counts and percentages. Baseline and follow-up parameters were compared using McNemar's test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The Bonferroni correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons. All hypotheses tested were two-tailed with a p<0.05 for type I error. All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 24 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

ResultsA total of 114 patients were included in the study. Nine (7.9%) patients died during follow-up. We followed 105 patients (mean age 50.4 years, 67 female) for a mean of 6.2±1.3 years. The main causes of death were infections (44%), refractory disease (33%) and cardiovascular events (22%). The majority of patients (91%) were ANCA-positive at diagnosis. Over 84% of patients were treated with glucocorticoids, 17% with azathioprine and 50% with cyclophosphamide. Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| n=105 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 50.4 (95% CI 47.4-53.4) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 67 (64) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 70 (66) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 30 (28) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 74 (70) |

| Systemic involvement | |

| Eyes, n (%) | 35 (33) |

| Ears, n (%) | 19 (18) |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 1 (0.9) |

| Musculoskeletal, n (%) | 42 (40) |

| Upper respiratory tract, n (%) | 87 (83) |

| Lower respiratory tract, n (%) | 77 (73) |

| Kidney, n (%) | 56 (53) |

| Central nervous system, n (%) | 14 (13) |

| Peripheral nervous system, n (%) | 23 (22) |

| Skin, n (%) | 9 (8.5) |

| BVAS, mean | 10.4 (95% CI 9.5-11.2) |

| Echocardiography | |

| Ao, mm | 31.7 (95% CI 31.0-32.3) |

| LA, mm | 36.1 (95% CI 35.2-37.1) |

| IVS, mm | 10.6 (95% CI 10.2-11.0) |

| PW, mm | 10.4 (95% CI 10.1-10.6) |

| LVDD, mm | 45.2 (95% CI 44.2-46.3) |

| LVSD, mm | 24.4 (95% CI 23.4-25.3) |

| RVD, mm | 29.2 (95% CI 28.2-30.2) |

| PA, mm | 19.7 (95% CI 19.3-20.1) |

| IVC, mm | 17.0 (95% CI 16.6-17.5) |

| PAT, ms | 129.4 (95% CI 125.8-133.0) |

| RVSP, mmHg | 33.2 (95% CI 32.1-34.4) |

| LVEF, % | 62.8 (95% CI 61.4-64.1) |

| TAPSE, mm | 21.5 (95% CI 20.8-22.2) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.3 (95% CI 1.1-1.4) |

| hs-CRP, mg/dl | 2.1 (95% CI 1.3-2.9) |

| ANCA-positive, n (%) | 96 (91) |

| MPO-ANCA, n (%) | 11 (10) |

| PR3-ANCA, n (%) | 85 (81) |

ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; Ao: ascending aorta; CI: confidence interval; IVC: inferior vena cava; IVS: intraventricular septum; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LA: left atrium; LVDD: left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVSD: left ventricular systolic diameter; MPO-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting myeloperoxidase; PA: pulmonary artery; PAT: pulmonary acceleration time; PR3-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting proteinase 3; PW: posterior wall; RV: right ventricle; RVD: right ventricular diameter; RVSP: right ventricular systolic pressure; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

AR was diagnosed in 43% of patients at baseline and was the most common valvular lesion. Moreover, it was the only valve involvement that significantly increased during observation (p=0.01) (Figure 1). Two patients (1.9%) underwent surgical valve replacement due to significant regurgitation. Nine (8.5%) patients were diagnosed with aortic stenosis, two of whom required cardiac surgery during the follow-up period. Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation (grade 2 or higher) was diagnosed less frequently and did not change during follow-up.

During observation, levels of PR3-ANCA (p=0.048) and D-dimer (p<0.0001) decreased significantly at the follow-up visit (Table 2). There were no significant differences in laboratory parameters between patients with and without progression of AR, except for D-dimer (Table 3). In a multivariate model, only D-dimer concentration predicted progression of AR in this patient group (odds ratio 8.0, 95% confidence interval 1.7–38.2, p=0.01) (Table 4).

Comparison of GPA patients at baseline and follow-up visits.

| Baseline | Follow-up | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | |||

| Ao, mm | 31.7±3.4 | 31.98±3.6 | 0.010 |

| LA, mm | 36.1±4.8 | 36.33±4.8 | 0.008 |

| IVS, mm | 10.6±1.9 | 10.67±1.8 | 0.116 |

| PW, mm | 10.4±1.3 | 10.39±1.4 | 0.218 |

| LVDD, mm | 45.2±5.5 | 45.94±5.7 | 0.001 |

| LVSD, mm | 24.4±4.7 | 24.59±5.1 | 0.173 |

| RVD, mm | 29.2±5.3 | 29.55±4.7 | 0.565 |

| PA, mm | 19.7±2.1 | 20.05±2.1 | 0.004 |

| IVC, mm | 17.0±2.4 | 16.8±2.5 | 0.951 |

| PAT, ms | 129.4±18.6 | 126.79±19.2 | 0.243 |

| RVSP, mmHg | 33.2±5.8 | 33.35±6.8 | 0.849 |

| LVEF (%) | 62.77±7.1 | 63.1±7.2 | 0.144 |

| Mitral regurgitation, n (%) | 35 (33) | 37 (35) | 0.030 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, n (%) | 38 (36) | 41 (39) | 0.112 |

| Aortic regurgitation, n (%) | 45 (43) | 54 (51) | 0.014 |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 11 (10) | 16 (15) | 0.267 |

| LV diastolic dysfunction, n (%) | 32 (30) | 33 (31) | 0.627 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 21.52±2.5 | 21.40±2.6 | 0.855 |

| PR3-ANCA, U | 32.38 (1.2–230) | 23.47 (0.7–130) | 0.050 |

| MPO-ANCA, U | 5.67 (1.1–13.5) | 3.51 (0.4–19) | 0.373 |

| D-dimer, ng/ml | 2011.70 (170–21 483) | 801.36 (162–7118) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.27 (0.6–3.3) | 1.19 (0.7–3.7) | 0.199 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dl, mean | 2.12 (0.6–14) | 1.44 (0.04–4.5) | 0.607 |

Ao: ascending aorta; CI: confidence interval; IVC: inferior vena cava; IVS: intraventricular septum; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricular; LVDD: left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVSD: left ventricular systolic diameter; MPO-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting myeloperoxidase; PA: pulmonary artery; PAT: pulmonary acceleration time; PR3-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting proteinase 3; PW: posterior wall; RV: right ventricle; RVD: right ventricular diameter; RVSP: right ventricular systolic pressure; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Comparison of baseline results between patients with and without aortic disease progression.

| No AR progression (n=89) | AR progression (n=16) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 49.0 | 56.9 | 0.048 |

| BVAS | 10.4 | 10.3 | 0.720 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dl | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.223 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.846 |

| D-dimer ≤500 ng/ml, % | 49.4 | 20 | 0.036 |

| MPO-ANCA, U | 5.8 | 5.6 | 0.405 |

| PR3-ANCA, U | 35.0 | 20.6 | 0.852 |

AR: aortic regurgitation; BVAS: Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; MPO-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting myeloperoxidase; PR3-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting proteinase 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with the progression of aortic regurgitation.

| Variable | Univariate analysis, OR (95% CI) | p | Multivariate analysis, OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-dimer | 3.9 (1.0–14.9) | 0.040 | 8.0 (1.7–38.2) | 0.010 |

| Age | 1.1 (1.00–1.10) | 0.070 | ||

| Sex | 0.5 (0.2–1.8) | 0.327 | ||

| BVAS | 1.2 (0.4–3.4) | 0.767 | ||

| hs-CRP | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.340 | ||

| PR3-ANCA | 1.7 (0.5–5.6) | 0.413 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) | 0.562 |

BVAS: Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; CI: confidence interval; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; OR: odds ratio; PR3-ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies targeting proteinase 3.

The main conclusion of this study is that not only is AR the most common valvular disease in patients with GPA, but aortic valves are also most likely to degenerate in GPA.

Cardiac valve involvement is a rare manifestation of GPA. Several mechanisms have been reported to be responsible for valvular disease, including accelerated degeneration, endocardial masses, and rarely, valve perforation.16 The most commonly reported valvular presentation is AR.10,11,13 In our previous study, AR was significantly more common in GPA patients than in the control group.11 The present study confirms this observation. However, this time we went a step further and assessed valve involvement over a longer period of time. In a study by Hazebroek et al., AR was observed in only 5% of patients with GPA, but the authors considered regurgitation of grade 3 or more,12 whereas our study examined AR of any degree, even mild. McGeoch et al. reported a low incidence (only 1.6%) of any valvular disease in patients with GPA, but in their cohort all patients diagnosed with cardiac involvement presented symptoms and none of these valvular manifestations were found during routine cardiac examinations in asymptomatic patients.17

Usually only one valve is involved in the course of GPA, but multiple valve disease has been reported.18-20 In the literature, most patients with GPA-related AR have undergone surgical intervention, but these patients usually had significant symptomatic AR (at least grade 3).10,21 In the present study, all grades of AR were analyzed. During follow-up, only two (1.9%) patients with AR required surgery, a comparable figure to other reports of significant AR.12,17

In the overview by Al-Habbaa et al. describing valvular involvement in GPA,13 which included 36 case reports, the aortic valve was involved in 15 (41.7%) cases: 13 of AR, one of aortic stenosis and one of aortic vegetation. The mitral valve was affected in nine (25%) patients: seven with mitral regurgitation, one with a mitral mass, and one with mitral prolapse. Combined aortic and mitral valve lesions were reported in nine (25%) patients. Tricuspid valve involvement was found in only three cases (8.3%). In this overview, most patients received immunosuppressive therapy (80.5%), but only six improved or showed no deterioration, while most patients underwent valve replacement.

Infective endocarditis should always be excluded before assuming an association between significant valvular heart disease and GPA.22 In Mahr at al.’s study, 6% of patients with infective endocarditis were found to be positive for both PR3-ANCAs and MPO-ANCAs. Subacute endocarditis was more frequently associated with PR3-ANCAs and less frequently with MPO-ANCAs.23

In our study, only D-dimer concentration was predictive of AR progression. This may be related to the previously reported finding that, in this group of patients, elevated D-dimer levels were associated with inflammation and disease activity.24

There are no specific guidelines for the management of GPA-related cardiac valve disease. Future clinical trials are needed to determine the pathogenesis and treatment of this complication of GPA. Routine cardiac examination and echocardiography in patients with GPA should therefore be implemented as early as possible to manage these rare but potentially fatal cardiac complications.

Most of the available data on valve involvement in GPA are case studies of patients with significant symptomatic valvular disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first long-term observation to analyze valve involvement in GPA patients.

Another strength of our study is its prospective nature, with systematic collection of laboratory and echocardiographic data, whereas previous studies were case–control and retrospective in nature. Additional advantages of this study are the homogeneity of the study group (only GPA patients were included), the large number of study participants, and its long-term follow-up.

Limitations of the studyThis study was conducted at a single center and there was no control group.

ConclusionsInvolvement of the heart valves is a common finding in patients with GPA, but significant valvular disease is a rare complication. The most common valvular disease in this group of patients is AR. Aortic valves are also the most prone to degeneration in the course of the vasculitis. Systematic cardiac monitoring, including echocardiography, can contribute to the early detection and appropriate treatment of AR and should be central to the long-term management of patients with vasculitis. There is a need for studies on larger groups of patients, also treated with biological drugs, in the context of the management and treatment of patients with aortic valve disease.

FundingThe authors have no funding to disclose.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.