Stanford type A aortic dissection is a rare phenomenon with high short-term mortality and clinical manifestations that can make differential diagnosis a lengthy process requiring several diagnostic examinations.

ObjectivesBased on a case report, the aim is to highlight the importance of physical examination in the initial management of these patients and of rapid access to a surgical center. A brief review follows on the diagnosis and treatment of ascending aortic dissection, and its specific nature in Marfan syndrome.

Case reportA 33-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department of a district hospital with chest and back pain associated with vomiting, 20 hours after symptom onset. Initial physical examination revealed an aortic systolic murmur and musculoskeletal morphological abnormalities compatible with Marfan syndrome. Given suspected aortic dissection, a transthoracic echocardiogram was immediately performed, which showed an extensive intimal flap originating at the sinotubular junction. He was transferred to the cardiothoracic surgery department of a referral hospital where he was treated by a Bentall procedure.

ConclusionIn this case, careful physical examination during initial assessment raised the suspicion that this patient was in a high-risk group for aortic dissection, thus avoiding unnecessary and lengthy exams. This diagnosis requires emergent surgical treatment, and so direct contact in real time between those making in the diagnosis and the surgeon is essential, as well as protocols governing immediate access to a surgical center.

A Dissecção da Aorta tipo A de Stanford é um fenómeno raro, com alta mortalidade a curto prazo e com manifestações clínicas que por vezes tornam o diagnóstico diferencial um processo moroso pela necessidade de realização de várias modalidades de exames complementares no Serviço de Urgência.

ObjectivosAtravés da alusão a um caso clínico, pretende-se realçar a importância do exame objectivo na abordagem inicial destes doentes e da rapidez do acesso a um centro cirúrgico. É feita uma breve revisão acerca do diagnóstico e tratamento da Dissecção da Aorta Ascendente, e das particularidades desta na Síndrome de Marfan.

Caso clínicoHomem de 33 anos, admitido no Serviço de Urgência de um Hospital Distrital com quadro de dor dorsal e pré-cordial associada a vómitos, com 20 horas de evolução. O exame objectivo inicial mostrou a presença de sopro sistólico no foco aórtico e anomalias morfológicas músculo-esqueléticas compatíveis com Síndrome de Marfan. Com a suspeita de Dissecção da Aorta, realiza-se imediatamente ecocardiograma transtorácico que mostrou exuberante flap intimal com origem na junção sino-tubular. É transferido para o Serviço de Cirurgia Cárdio-Torácica do hospital de referência onde foi tratado com cirurgia tipo Bentall.

ConclusãoNo caso apresentado, uma primeira abordagem na qual se realizou um exame objectivo atento levantou a hipótese de o doente pertencer a um grupo de alto risco para Dissecção da Aorta, evitando exames complementares desnecessários e morosos. Este diagnóstico exige tratamento cirúrgico emergente, de modo que se torna imperiosa a existência de um contacto directo, em tempo real, entre quem faz o diagnóstico e o cirurgião, bem como protocolos de acesso imediato a um centro cirúrgico.

We present the case of a 33-year-old patient in whom a setting of intense precordial pain began, which was confined to this area for a few minutes, then radiated posteriorly and a few minutes later was located in the dorsal region only. These symptoms were accompanied by violent bouts of vomiting, of food and then watery fluid.

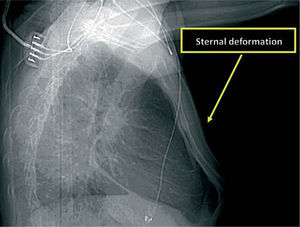

The patient was away from home at the time and went to the local health center, where he was given analgesics and antibiotics. As his symptoms continued, he then went to the emergency department of the district hospital in his area of residence, where he was admitted 20 hours after symptom onset. He was greatly distressed, sweating and with continuing bouts of vomiting. His blood pressure (BP) was 160/90mmHg and heart rate 95bpm. Cardiac auscultation revealed a grade 2/6 holosystolic murmur, more audible in the aortic area; pulmonary auscultation was normal, and posterior radial and tibial pulses were symmetrical. He presented no signs or symptoms of heart failure or hemodynamic instability. Abdominal palpation was normal. Physical examination showed the patient presented pectus carinatum (Figure 1) and some facial abnormalities, including retrognathia, right enophthalmos and arched palate; his fingers were long but joint mobility was normal.

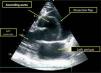

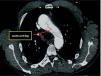

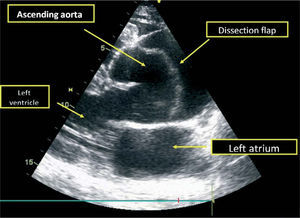

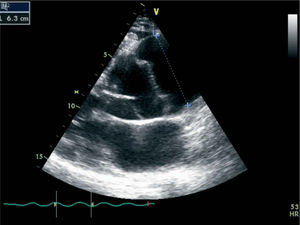

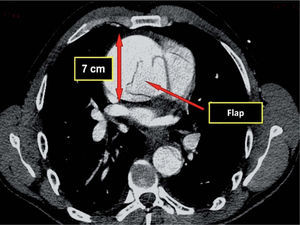

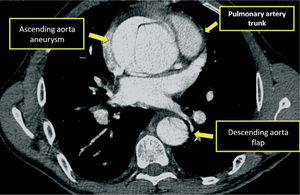

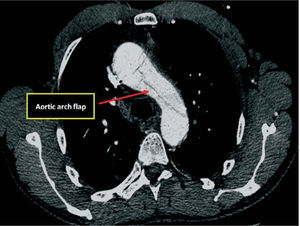

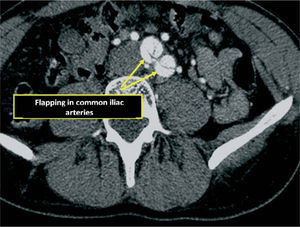

Given the presence of a previously undetected systolic murmur in the aortic area and the location of symptoms, as well as subtle morphological abnormalities, transthoracic echocardiography was performed. This revealed aneurysmal dilatation of the ascending aorta immediately distal to the aortic valve, and a linear membranous echogenicity was visualized in the area of the sinotubular junction, with an undulating motion and oriented transversally to the long axis of the vessel (Figures 2 and 3). Global systolic function was good and there was no evidence of wall motion abnormalities. Turbulent systolic flow was observed after the aortic valve, caused by mechanical disturbance due to interposition of the membrane, together with moderate aortic regurgitation. Therapy was begun with antihypertensives and beta-blockers, and analgesic medication was increased. CT angiography was immediately performed, which confirmed a Stanford type A aortic dissection, extending from the sinotubular junction to both common iliac arteries (Figures 4-7).

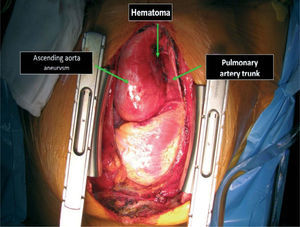

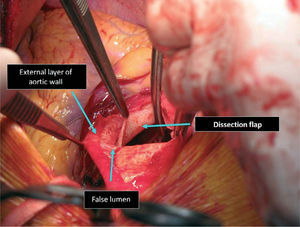

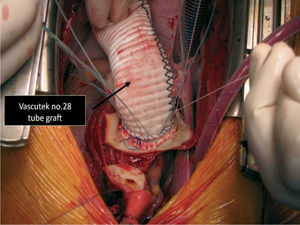

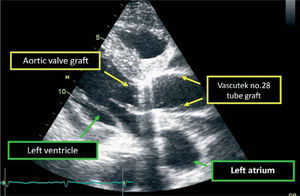

The patient was transferred by emergency ambulance to the cardiothoracic surgery department of a referral hospital, where he was hemodynamically stable on arrival. Dissection was confirmed during surgery, with the entrance involving almost the entire perimeter of the ascending aorta 2–3cm above the valve plane (Figures 8 and 9). A Bentall procedure was performed, the aortic valve being replaced by a 27mmSt. Jude prosthesis and the ascending segment of the aorta by a 28mm Vascutek tube graft, with the coronary arteries subsequently being reimplanted in the graft (Figure 10). Arterial cannulation was via the right axillary artery. Figure 11 shows the postoperative echocardiogram.

The immediate postoperative period was uneventful, with low blood loss, good urinary output and hemodynamic stability (systolic BP around 90mmHg and diastolic BP around 60mmHg). Ventilatory support was gradually reduced and the patient was extubated 20 hours after the operation. He was transferred from the intensive care unit on the third day and discharged home on the 11th day, medicated with beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors.

DiscussionAortic dissection is uncommon, with 2.6 to 3.5 cases annually per 100 000 population in western Europe1. The main risk factors in older individuals are hypertension, atherosclerosis, previous cardiac surgery and percutaneous procedures involving the aorta1. In younger individuals, the principal risk factor is connective tissue disease, most commonly Marfan syndrome.

Marfan syndrome is the most prevalent connective tissue disease of genetic origin, with autosomal dominant inheritance of variable penetrance. It is caused by mutations in the gene coding for fibrillin-1 (FBN-1), an extracellular matrix protein, and possibly in the MFS2 gene2. Almost two hundred different mutations in the FBN-1 gene have been identified, which largely explains the heterogeneity of phenotypic expression in different organs and the varying penetrance.

From a pathophysiological standpoint, various phenomena are implicated in the genesis of aortic alterations in patients with Marfan syndrome, particularly:

- –

non-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells and increased apoptosis, which appears to be the main cause of vessel dilatation3;

- –

increased production of metalloproteinases in smooth muscle, increasing elastolysis and causing degeneration and weakening of elastic fibers 3–5;

- –

increased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), which is associated with cystic medial degeneration6.

The Ghent criteria are used to establish a diagnosis of Marfan syndrome ( Table)7.

The Ghent criteria for diagnosis of Marfan syndrome

| Organ system | Major criteria | Minor criteria |

| Cardiovascular | — Dilatation of the ascending aorta and sinuses of Valsalva | — Dilatation of the pulmonary artery |

| — Dilatation or dissection of the descending aorta in patients aged <50 years | ||

| — Dissection of the ascending aorta | ||

| — Mitral valve prolapse | ||

| — Calcification of the mitral annulus in patients aged <40 years | ||

| Central nervous system | Lumbosacral dural ectasia 4 of the following: | |

| Musculoskeletal | — Facial appearance (dolicocephaly, | |

| — Pectus carinatum | malar hypoplasia, enophthalmos, retrognathia, down-slanting palpebral fissures) | |

| — Pectus excavatum requiring surgery | ||

| — Arm span to height ratio >1.05 or upper to lower segment ratio <0.86 | ||

| — Joint hypermobility | ||

| — Scoliosis or spondylolisthesis | — Pectus excavatum not requiring surgery | |

| — Elbow extension <170° | — Arched palate | |

| — Pes planus | ||

| — Protrusio acetabulae | ||

| Ocular | Ectopia lentis | — Myopia |

| — Córnea aplanada | ||

| — Hypoplastic iris or ciliary muscle | ||

| Pulmonary | — Pneumothorax | |

| — Apical blebs | ||

| Cutaneous | — Striae not associated with marked weight changes or pregnancy | |

| — Incisional or recurrent herniae |

Diagnosis of Marfan syndrome is based on the following criteria7:

- •

If there is no family history, major criteria in at least two different organ systems and involvement of a third.

- •

If a mutation known to cause Marfan syndrome is detected, one major criterion in an organ system and involvement of a second.

- •

In cases with a family history of Marfan syndrome, one major criterion in an organ system and involvement of a second.

- •

Minor criteria merely serve to assess the severity of the involvement of different systems and are not diagnostic.

The criteria present in this patient are highlighted in blue.

Periodic imaging studies to reassess the entire aorta are recommended, at three-monthly intervals in the first year, followed by annual assessment9.

Aortic dissection results from separation of the layers of the vessel wall, thus creating two lumens, which may or may not be perfused. The dissection may extend to branches of the aorta that supply various organs and impair perfusion, notably in the heart, central nervous system, intestines and kidneys. Proximal dissection of the aortic wall carries a very high risk of rupture, which is rapidly lethal, due to massive hemorrhage, or pericardial tamponade if the rupture occurs in the pericardial space1. The risk of rupture in cases of untreated dissection of the ascending aorta is 90%, of which 75% cause bleeding into the pericardium, pleural space or mediastinum8. Mortality associated with acute proximal aortic dissection is estimated at 24% in the first 24 hours, 29% within 48 hours, and 50% after two weeks if treated by medical therapy alone. With surgical correction, the Figures are 10%, 12% and 20%, respectively1,9.

Untreated cases involving only the descending aorta have a better prognosis, with mortality of 11% at one month, 16% at one year and 20% at five years1. Following diagnosis of proximal aortic dissection, emergency surgical treatment is mandatory, except in cases with severe neurological damage that is deemed irreversible10.

In the case presented, we opted for a Bentall procedure since the sinuses of Valsalva were involved and the underlying connective tissue disease could affect any remaining tissue. In addition, macroscopically the valve leaflets presented some focal thickening, which subsequent anatomopathological examination revealed to be fibrous with amorphous basophilic deposits.

The Bentall procedure has shown extremely favorable results in terms of prognosis for patients with Marfan syndrome, with over 90% five-year survival in cases of non-emergent surgery, and slightly lower in emergent cases11,12.

The main complications of this type of reconstruction are coronary ostial stenosis, blood loss during implantation of the ostia in the tube graft and problems of visceral perfusion due to absence of thrombosis of the false lumen distal to the ascending aortic prosthesis.

The results of valve-sparing techniques (David and Yacoub procedures) are more uncertain in terms of prognosis10.

In the surgical center involved in the present case, 42 Bentall procedures had been performed up to 2008, degenerative ascending aortic aneurysm being the indication in 76.3% of cases, Stanford type a aortic dissection in 14.3%, and Marfan syndrome without acute dissection in 10%. Of these patients, 14.3% were operated emergently. With regard to prognosis, overall survival at 30 days was 92.8% (all evolving to NYHA class I), with 90.4% survival at one year and 85.7% at five years (the latter figure only includes patients operated more than five years previously). Since 2008, there have been a further 35 procedures of this type, many of which were performed in recent months, and medium- and long-term results are currently being evaluated.

Against this background, the authors consider that protocols governing immediate access to a surgical center are essential, and given the situation in Portugal, this is even more important for peripheral hospitals from which patients need to be transferred. The lack of immediately available transport and designated qualified staff results in logistical and bureaucratic obstacles that lead to unnecessary and life-threatening delays.

The favorable outcome in the case presented further highlights the importance of direct real-time contact between the team involved in diagnosis and the surgeon, which enables constant monitoring of the patient's clinical status by the various health providers, preoperative optimization of the patient's condition, and advance preparation of the specific logistical resources required for surgical treatment of each case.

Adjuvant medical therapy in cases of ascending aortic dissection when surgical treatment is not immediately available includes pain relief and reduction of systolic BP to below 110mmHg. Morphine is the first-line drug for the former, while BP control can be achieved with intravenous beta-blockers such as metoprolol, esmolol (loading dose 500μg/kg, followed by 50μg/kg/min in perfusion) or labetolol (loading dose 20mg, followed by 2mg/min in perfusion), either alone or in combination with vasodilators such as ACE inhibitors or nitroprusside (initial perfusion rate 0.3μg/kg/min)8.

Physical examination of this patient revealed certain criteria of Marfan syndrome, which, taken together with his symptoms, increased suspicion of aortic dissection in an individual with a predisposition for this entity, and was an important consideration in referring him immediately for appropriate diagnostic exams.

Confirmation of dissection with aneurysmal dilatation of various portions of the aorta in this patient fulfilled the number of criteria required for a diagnosis of Marfan syndrome (indicated by asterisks in Table).

With regard to prognosis, it is estimated that around a third of patients with aortic dissection treated successfully by surgery will suffer distal extension of the dissection or rupture of the vessel, or undergo a new intervention due to aneurysm formation13,14.

Long-term follow-up of such cases requires aggressive medical therapy, chiefly to control blood pressure, recommended target BP in Marfan syndrome being <135-80 mmHg9, as well as heart rate, which evidence suggests should be <60 bpm9,15. Beta-blocker therapy is essential.

ConclusionIn the case presented, careful attention to signs and symptoms enabled appropriate diagnostic exams to be requested rapidly. Simple transthoracic echocardiography, which can now be performed at the patient's bedside, led to the immediate diagnosis of aortic dissection, resulting in prompt arrival of the patient in the operating room.

We would stress again the importance of careful observation and thorough physical examination, even in emergency cases where prompt action is essential.

We also emphasize the importance of protocols governing transfer and immediate access to a referral center with cardiothoracic surgery, particularly in the case of peripheral hospitals where patients may need to be transported long distances.

Direct contact in real time between those involved in diagnosis and the surgical team is also to be encouraged in order to keep the latter updated on the patient's clinical status and specific needs, enabling advance preparation of the logistical resources required for the intervention.