Approximately 60000–100000 Americans die from deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism annually, while the overall estimate of individuals affected is 30000–600000. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement has emerged as a break-through endovascular technique which has gained increasing acceptance and has probably saved thousands of lives by preventing fatal thromboembolic events. However, in the absence of a national IVC filter registry an accurate estimate of device complications is currently unavailable.

We present a case of symptomatic IVC syndrome due to IVC interruption in a patient with a non-retrievable IVC filter. This patient was initially managed with balloon angioplasty and mechanical thrombectomy with suboptimal results and subsequently with stent placement through the IVC filter.

Cerca de 60000 a 100000 americanos morrem anualmente de trombose venosa profunda (TVP) ou de embolia pulmonar (EP), sendo a estimativa global de doentes afetados de 300000 a 600000. A colocação do filtro na veia cava inferior (VCI) surgiu como uma técnica endovascular inovadora que tem ganho uma aceitação crescente e tem salvo provavelmente milhares de vidas de eventos tromboembólicos fatais. Contudo, devido à falta de um registo nacional de filtros de VCI, não está atualmente disponível uma estimativa precisa das complicações do equipamento.

Apresentamos um caso de uma síndrome de VCI sintomática devida à interrupção da VCI num doente com um filtro de VCI não recuperável. Este doente foi inicialmente tratado com angioplastia por balão e trombectomia mecânica com resultados suboptimizados e posteriormente com implantação de stent através de um filtro na VCI.

According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, approximately 60000–100000 Americans die from deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) annually, while the overall estimate of individuals affected is 30000–600000.1 Of those affected, 33% will have a recurrence within the next 10 years. The mainstay of DVT/PE treatment today is anticoagulation; however, many patients do not qualify for anticoagulation due to important comorbidities such as bleeding diathesis, active gastric ulcers, or frequent falls.

The prevention of PE in patients with lower extremity DVT by surgical interruption of the inferior vena cava (IVC) was first suggested by Trousseau in 1868 and was successfully performed by Bottini in 1959.2 The first mechanical IVC filter (Mobin-Uddin) was used in 1967 as a novel device that would trap larger thrombi migrating from the deep venous system of the lower extremities to the pulmonary arteries.3 Today the endovascular placement of IVC filters has become a simple and safe routine endovascular procedure.

According to the 2012 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines, the use of an IVC filter is indicated in patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg and contraindication to anticoagulation (grade 1B).4 An accurate number of IVC filter implantations in the US is currently unavailable despite an attempt by the American Venous Forum to form an IVC registry.5 It is estimated that approximately 259000 IVC filters were implanted in 2012.6

Safety of inferior vena cava filtersThe use of IVC filters has increased in recent years due to their ease of use and proven clinical benefits in selected patient populations. However, in 2010 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that “implanting physicians and clinicians responsible for the ongoing care of patients with retrievable IVC filters consider removing the filter as soon as protection from PE is no longer needed”. This recommendation resulted from 921 device adverse event reports including migration, embolization of device components, venous perforation and IVC filter fracture.8 An accurate estimate of IVC filter complications in the US is currently unavailable as most of these adverse events are clinically silent.

The British Society of Interventional Radiology Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filter Registry was created to assess current practice in the UK and to address safety concerns. In their report on 1434 IVC filter placements the rate of complications was 3.5%.7

Therefore, the overall risk of IVC obstruction after filter placement is unknown.

Endovascular management of inferior vena cava filter obstructionEndovascular techniques to treat deep venous system stenosis or obstruction have attracted increasing interest over the last decade. Large series of obstructive lesions in the IVC treated percutaneously with angioplasty or stenting have demonstrated the safety of the technique and excellent stent patency (82% in two years) with significant symptomatic relief of swelling, pain and ulcer formation.9

Stenting of occluded IVC filters was reported in a large case series of 708 patients with stenting due to post-thrombotic iliocaval outflow obstruction. In their observational study Neglén et al.9 reported 25 cases of IVC filter occlusion which were successfully managed with stent placement across the IVC filter. In all these cases the IVC filter was significantly displaced or deformed. There were no perioperative complications. In patients with stenting through the IVC filter, 54-month secondary stent patency was slightly lower (74%) than in the other procedures (86%). However logistic regression analysis associating patency rates and occlusive disease demonstrated that patency was not associated with stenting of the IVC filter but with the severity of post-thrombotic disease.9

Case reportA 64-year-old Caucasian female with prior history of lower extremity DVT, post-thrombotic syndrome, venous insufficiency and recent IVC filter placement was referred to our clinic with worsening leg swelling, pain and non-healing ulcers bilaterally. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, seizure disorder and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She had a previous hysterectomy, cholecystectomy and colon repair, which were all reportedly uncomplicated.

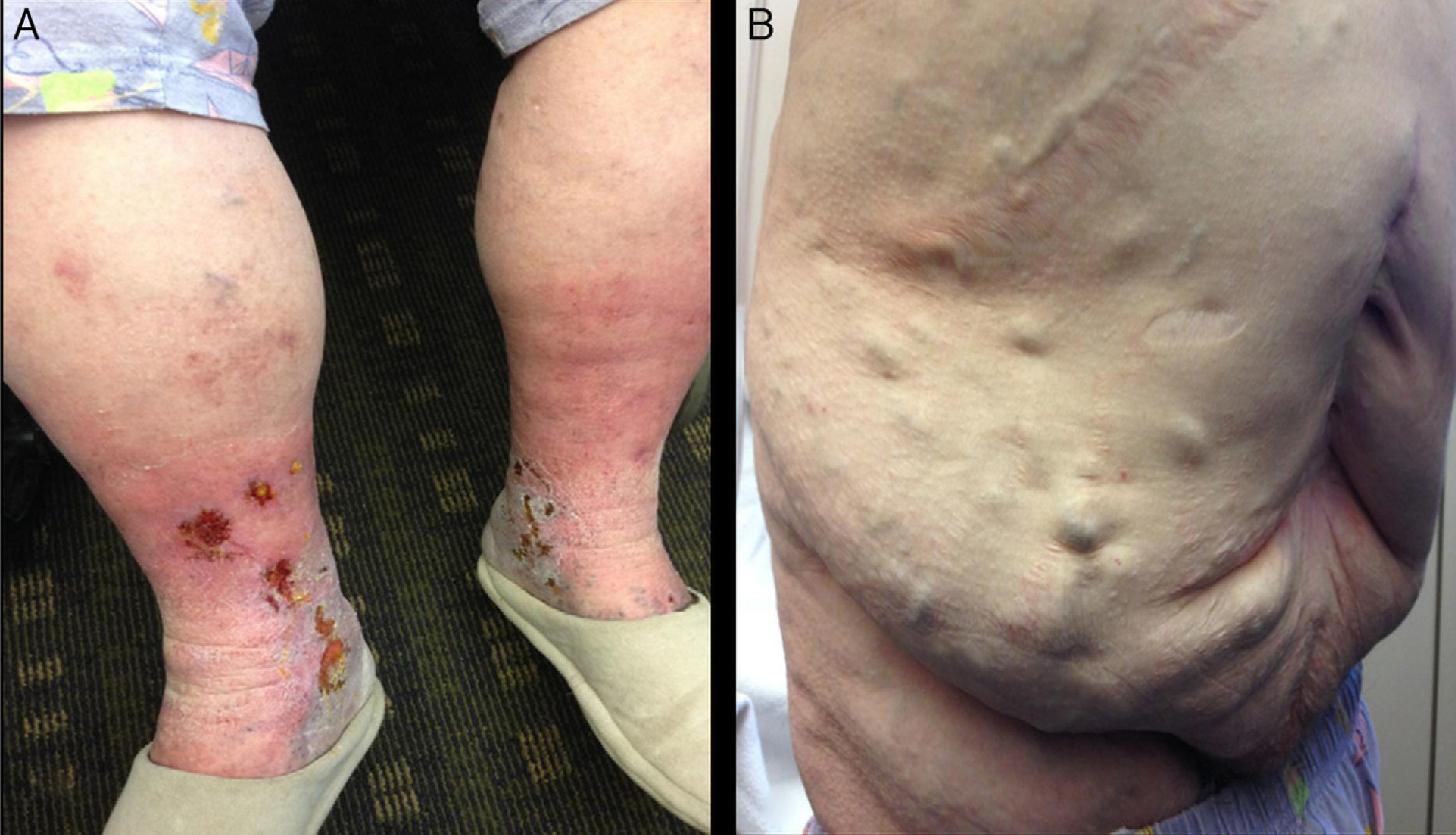

Her physical examination revealed bilateral telangiectasias, reticular and varicose veins with worsening edema which reportedly increased from the ankle area to the mid calf, and skin pigmentation changes to the mid-lower calf areas. Chronic lipodermatosclerosis had already been noticed in the medial ankle areas, associated with worsening chronic venous ulcers lower on the medial ankle. The ulcers were tender, shallow and exudative with a granulation base (Figure 1A). Despite increased dosage of diuretics and leg elevation for many hours a day, they had appeared to be progressively worsening in recent weeks. Dilated abdominal veins were noticed more prominently in the lower abdomen, forming a caput medusae which the patient stated that she had not noticed until recently (Figure 1B).

As symptoms and signs involved the lower extremities bilaterally, suggesting IVC stenosis or occlusion, computed tomography (CT) angiography during the venous phase was performed. The angiogram showed absence of flow above the IVC filter, and the patient was accordingly referred for invasive venography and probable endovascular intervention.

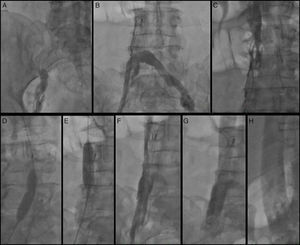

A 6F sheath was placed in the right common femoral vein and was used for the right femoral venogram. There appeared to be total occlusion of the right common iliac vein extending to the site of the IVC filter (Figure 2A). The exact type of IVC filter was unknown at the time of the procedure. With the use of a Glidewire (Terumo Interventional Systems, Somerset, NJ) a 0.035″ Quick-Cross support catheter (Spectranetics, Colorado Springs, CO) was crossed over to the left common femoral vein and a left femoral angiogram was performed by hand injection through the Quick-Cross catheter. A complete occlusion of the IVC was identified below the IVC filter (Figure 2B). The Quick-Cross catheter was then positioned above the IVC filter and an IVC venogram above the occlusion was performed. This revealed significant IVC stenosis below the renal vein take-off level (Figure 2C).

(A) Right femoral venogram; (B) left femoral venogram through Quick-Cross catheter demonstrating IVC interruption at the level of the IVC filter; (C) selective IVC venogram through Quick-Cross catheter above the IVC filter showing IVC stenosis; (D and E) balloon angioplasty of the IVC and right femoral vein through the IVC filter; (F) angiogram after percutaneous balloon angioplasty; (G and H) angiogram after stent placement.

The decision was taken for endovascular intervention. The right femoral sheath was exchanged for a short 11F sheath. Percutaneous balloon angioplasty of the IVC was performed with a 16 mm×40 mm XXL balloon dilation catheter (Boston Scientific, St Paul, MN) and a 12 mm×40 mm Armada balloon catheter (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL) within and above the IVC filter (Figure 2D and E). Due to persistence of slow flow, the Angiojet Ultra Thrombectomy system (Bayer Healthcare, Minneapolis, MN) was used to deliver 20 ml alteplase (5 mg/ml), followed by mechanical thrombectomy and aspiration. Despite angioplasty and mechanical thrombectomy, venous flow remained suboptimal throughout the lower IVC (Image 2F). Therefore a 20 mm×80 mm WALLSTENT (Boston Scientific, St Paul, MN) was deployed through the previously placed IVC and optimal flow was established at the level of the IVC filter (Figure 2G) and above (Figure 2H).

DiscussionIn our case report a non-retrievable IVC filter apparently caused IVC interruption and IVC syndrome with worsening patient symptoms. The filter appeared to be in a much lower position than usual and it is unclear whether it had implanted inappropriately or had migrated. Furthermore, given the patient's history of multiple abdominal surgeries, it is probable that IVC stenosis may have been present before the IVC filter procedure.

ConclusionsIVC filter placement has emerged as a break-through endovascular technique which has gained increased acceptance and has probably saved thousands of lives by preventing fatal thromboembolic events. However, in the absence of a national IVC filter registry an accurate estimate of device complications is currently unavailable. Increasing reports of adverse events have raised the concern that too many permanent IVC filters may be currently placed in the US and the FDA has recommended the retrieval of filters when they are no longer needed. Development of IVC syndrome due to IVC interruption at the level of the filter is an under-recognized procedural complication with unknown incidence which may result in important morbidity. When suspected, it can be confirmed with a CT angiogram during the venous phase and successfully treated with endovascular recanalization and stenting through the IVC filter

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.