To estimate the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of dabigatran in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in Portugal.

MethodologyA Markov model was used to simulate patients’ clinical course, estimating the occurrence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, and intra- and extracranial hemorrhage. The clinical parameters are based on the results of the RE-LY trial, which compared dabigatran with warfarin, and on a meta-analysis that estimated the risk of each event in patients treated with aspirin or with no antithrombotic therapy.

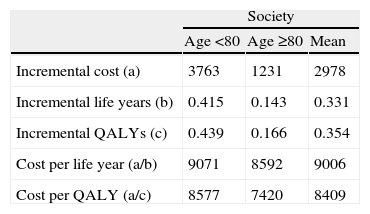

ResultsDabigatran provides an increase of 0.331 life years and 0.354 quality-adjusted life years for each patient. From a societal perspective, these clinical gains entail an additional expenditure of 2978 euros. Thus, the incremental cost is 9006 euros per life year gained and 8409 euros per quality-adjusted life year.

ConclusionsThe results show that dabigatran reduces the number of events, especially the most severe such as ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, as well as their long-term sequelae. The expense of dabigatran is partially offset by lower event-related costs and by the fact that INR monitoring is unnecessary. It can thus be concluded that the use of dabigatran in clinical practice in Portugal is cost-effective.

Estimar os rácios custo-efetividade e custo-utilidade associados à utilização de dabigatrano na prevenção de acidentes vasculares cerebrais e embolias sistémicas em doentes com fibrilhação auricular não valvular em Portugal.

MetodologiaFoi utilizado um modelo de Markov para simular a evolução dos doentes, estimando a ocorrência de acidentes vasculares cerebrais isquémicos e hemorrágicos, de acidentes isquémicos transitórios, de embolias sistémicas, de enfartes agudos do miocárdio e de hemorragias intra e extracranianas. Os parâmetros clínicos baseiam-se nos resultados do estudo RE-LY, que compara a utilização de dabigatrano com a de varfarina, e numa meta-análise em que se estimou o risco de ocorrência de cada evento em doentes medicados com ácido acetilsalicílico ou sem qualquer terapêutica antitrombótica.

ResultadosO dabigatrano proporciona, a cada doente, um incremento de 0,331 e de 0,354 anos de vida ajustados pela qualidade. Na perspetiva da sociedade, estes ganhos clínicos implicam um aumento da despesa em 2.978 €. Assim, o custo incremental por ano de vida ganho é de 9.006 €, sendo o custo incremental por ano de vida ajustado pela qualidade de 8.409 €.

ConclusõesOs resultados obtidos mostram que o dabigatrano diminui a quantidade de eventos, nomeadamente os de maior gravidade como os acidentes vasculares cerebrais isquémicos e hemorrágicos, bem como as respetivas sequelas de longo prazo. Os custos com dabigatrano são parcialmente compensados por uma diminuição dos custos decorrentes dos eventos, bem como pela ausência de monitorização do INR. Assim, pode concluir-se que a utilização de dabigatrano na prática clínica portuguesa é custo-efetiva.

atrial fibrillation

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

international normalized ratio

myocardial infarction

quality-adjusted life years

transient ischemic attack

value-added tax

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a supraventricular arrhythmia characterized by deterioration of atrial mechanical function resulting in increased risk of thromboembolic events such as ischemic stroke.1

Non-valvular AF (i.e. not resulting from rheumatic mitral valve disease, prosthetic valves or valve repair2) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, increasing with age; it has an estimated prevalence of 1–2%, and this figure is set to rise with aging populations.1 The overall prevalence of AF in the FAMA study, on a Portuguese population aged over 40, was 2.5%, but was significantly higher in those aged 70 or more (0.2% in those aged 40–49, 1.0% in those aged 50–59, 1.6% in those aged 60–69, 6.6% in those aged 70–79, and 10.4% in those aged 80 or over).3 There were an estimated 143000 cases in Portugal in 2012.

AF can be asymptomatic and remain undiagnosed: according to the Euro Heart Survey, only 69% of patients report symptoms.4 Appropriate screening (pulse taking and electrocardiography) is not always performed in clinical practice; the estimated rate of detection of AF in primary health care is 64%.5 There are also significant problems of patient awareness, as shown in the Portuguese FAMA study, in which only 62% of those with AF were aware of having the condition.3

The increased thromboembolic risk of these patients results in not only a doubling of mortality1 but also increased morbidity, a consequence of the main complication of AF, ischemic stroke, the incidence of which is three to four times higher in AF,6 which is thus one of the principal causes of ischemic stroke.7 In the Framingham study, the annual risk of stroke attributable to AF was 1.5% for those aged 50–59 and 23.5% for those aged 80–89.7 Furthermore, stroke associated with AF is generally more severe and leads to greater health care costs.8

The main treatment is currently vitamin K antagonists, usually warfarin, which reduces stroke risk by 64% compared to placebo and by 40% compared to aspirin.9 However, the complications associated with its use, including interactions with other drugs and dietary considerations, as well as the difficulty in maintaining the international normalized ratio (INR) within therapeutic and safety limits, mean that many eligible patients are not medicated with warfarin. In Portugal, only 38% of those eligible for anticoagulation receive warfarin and 40% receive no antithrombotic therapy at all.3

These difficulties have prompted a search for alterative therapies that are at least as effective and safe as warfarin but do not require repeated laboratory testing. However, up to now all attempts have failed; antiplatelet agents such as aspirin and clopidogrel provide inadequate protection against ischemia,10,11 while there are safety concerns with other anticoagulants such as ximelagatran and idraparinux.12,13

Dabigatran is an oral anticoagulant that acts through direct and selective inhibition of thrombin. Its dose-response effect is predictable, eliminating the need for routine INR monitoring. In the RE-LY clinical trial,14,15 in which over 18 000 patients with non-valvular AF were followed for a median of two years, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was associated with lower rates of stroke and systemic embolism than warfarin but similar rates of major bleeding, while dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with similar rates of stroke and systemic embolism to those associated with warfarin, as well as lower rates of major bleeding. Significantly lower rates of intracranial bleeding were observed with both doses of dabigatran than with warfarin. In 2011 dabigatran was approved by the European Medicines Agency for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular AF.

In the light of these results, dabigatran represents an important innovation not only for AF patients taking warfarin but also for those on other therapeutic regimens. Given the need to rationalize health care costs, the cost of any new drug must be weighed against the health gains it provides. For this reason, we performed an economic evaluation of dabigatran for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular AF.

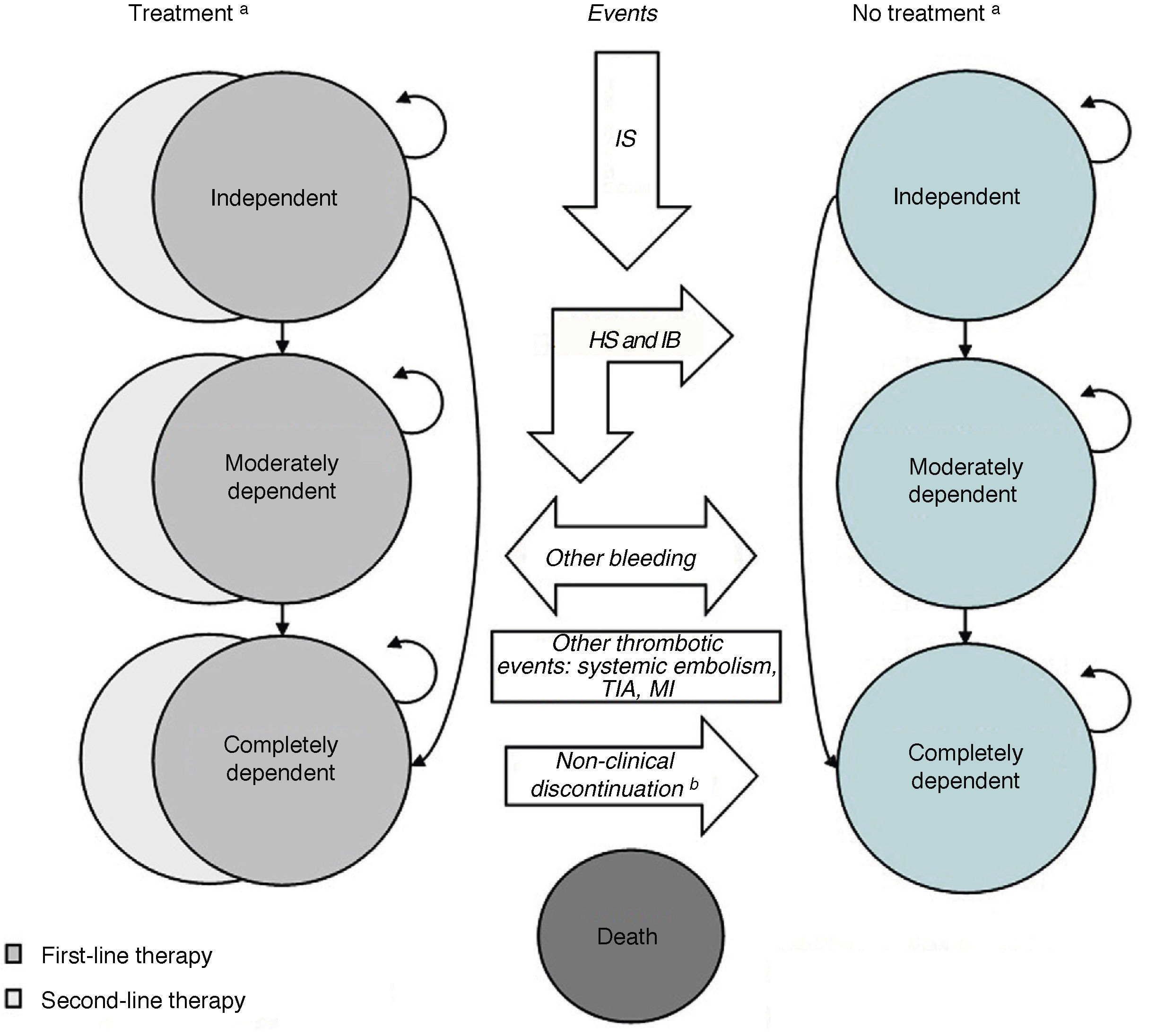

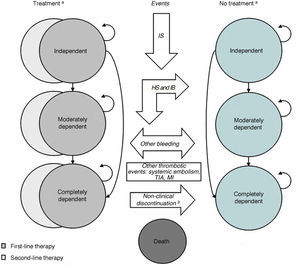

MethodsModelThe Markov model (Figure 1) used in this evaluation is based on those used in economic studies on the introduction of dabigatran in Canada16 and the United Kingdom,17 adapted to the Portuguese context. The model simulates patients’ clinical course in 3-month cycles to the end of their lives, applying a specified probability of the mutually exclusive occurrence of the major events in this population: death, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), systemic embolism, myocardial infarction (MI), and intra and extracranial bleeding. Minor bleeding, which can occur concomitantly with the other events, is also simulated.

An individual who has suffered a cerebral event (ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or intracranial bleeding) may lose their independence. Such patients are classified according to the modified Rankin scale (for stroke) or the Glasgow Outcomes scale (for intracranial bleeding) as independent, moderately dependent, or completely dependent. Treatment can be discontinued, permanently in the case of hemorrhagic stroke or intracranial bleeding, or temporarily due to extracranial bleeding or other reasons.

Such a simulation of a patient cohort can be used to estimate the costs and clinical consequences associated with different therapeutic options. In this case the model was used to predict costs, life years, and quality-adjusted life years (QALY) for the alternatives under analysis and to determine costs per life year and per QALY for the treatment with the best clinical results.

ComparatorThe choice of comparator (the therapeutic option to be replaced by the drug under assessment) is a crucial element in the design of an economic evaluation. Dabigatran is an alternative not only to warfarin but also to other therapeutic options for AF patients, particularly aspirin and no antithrombotic medication.

In the FAMA study,3 as stated above, only 38% of eligible patients were medicated with warfarin and 40% were receiving no treatment. For the construction of our model it was assumed that the rest were taking aspirin, and so the comparator used in our study is a weighted combination of warfarin, aspirin and no treatment.

Clinical and epidemiological dataThe model uses the results of the RE-LY trial,14,15 a direct comparison between warfarin and dabigatran in over 18 000 patients with non-valvular AF and moderate to high stroke risk randomized to 110 mg or 150 mg dabigatran twice daily or warfarin at doses adjusted for a target INR of 2.0–3.0 for a median of two years. The study took place between December 2005 and March 2009 in 44 countries around the world, including Portugal, where nine centers with 117 patients participated.

The study analyzed the occurrence of events in individuals taking warfarin and the relative risks of those taking dabigatran. The results showed that 110 mg dabigatran reduced the primary outcome (stroke or systemic embolism) by 10%, although it was not significantly superior to warfarin, with a better safety profile (20% less major bleeding than warfarin, p=0.003). The 150 mg dose was superior to warfarin, reducing the primary outcome by 35% (p<0.001) and major bleeding by 7% (without statistical significance). Dabigatran significantly reduced the incidence of intracranial bleeding, by 70% for the 110 mg dose and by 59% for the 150 mg dose (p<0.001).15

The only adverse effect that was significantly more common with dabigatran than with warfarin was dyspepsia (including abdominal pain), which occurred in 5.8% of patients in the warfarin group and in 11.8% and 11.3% in the 110 mg and 150 mg dabigatran groups, respectively (p<0.001 for both comparisons). Overall adverse event rates were similar between the treatment groups.

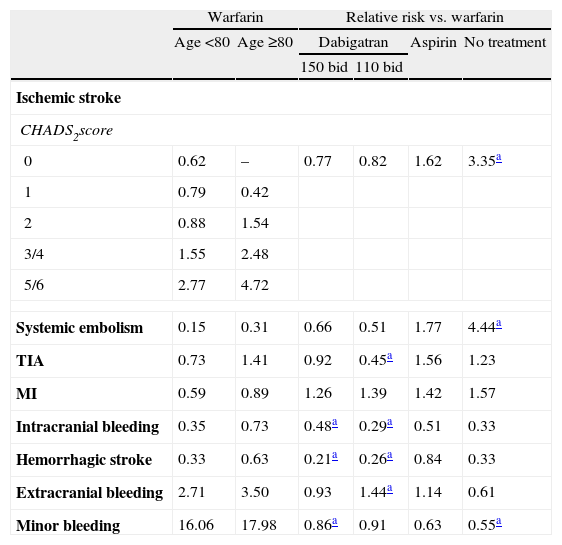

There has also been a meta-analysis18 that estimated the relative risk of various events in patients treated with aspirin and no treatment, patients’ ischemic stroke risk being stratified according to their CHADS2 score.18Table 1 shows the results, which differ from those in the RE-LY trial publications in accordance with the drug's approval by the European Medicines Agency, which recommends 150 mg dabigatran twice daily for patients aged under 80 and 110 mg twice daily for those aged 80 or over.19

Event rates per 100 person-years in patients taking warfarin and relative risks of other treatments.

| Warfarin | Relative risk vs. warfarin | |||||

| Age <80 | Age ≥80 | Dabigatran | Aspirin | No treatment | ||

| 150 bid | 110 bid | |||||

| Ischemic stroke | ||||||

| CHADS2score | ||||||

| 0 | 0.62 | – | 0.77 | 0.82 | 1.62 | 3.35a |

| 1 | 0.79 | 0.42 | ||||

| 2 | 0.88 | 1.54 | ||||

| 3/4 | 1.55 | 2.48 | ||||

| 5/6 | 2.77 | 4.72 | ||||

| Systemic embolism | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 1.77 | 4.44a |

| TIA | 0.73 | 1.41 | 0.92 | 0.45a | 1.56 | 1.23 |

| MI | 0.59 | 0.89 | 1.26 | 1.39 | 1.42 | 1.57 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.48a | 0.29a | 0.51 | 0.33 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.21a | 0.26a | 0.84 | 0.33 |

| Extracranial bleeding | 2.71 | 3.50 | 0.93 | 1.44a | 1.14 | 0.61 |

| Minor bleeding | 16.06 | 17.98 | 0.86a | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.55a |

The table shows that compared to warfarin, dabigatran significantly reduces the events under consideration, particularly ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, systemic embolism, TIA, intra- and extracranial bleeding (the latter two only in patients aged under 80), and minor bleeding. These clinical advantages are naturally more marked in relation to aspirin and no treatment. A slightly lower rate of MI was also observed in the warfarin group, although without statistical significance.15

The epidemiological data from the FAMA study were used to estimate the proportion of men to women with AF in Portugal and their mean age,3 giving a figure of 55% males in the population aged under 80 and 26% in the older age-group.

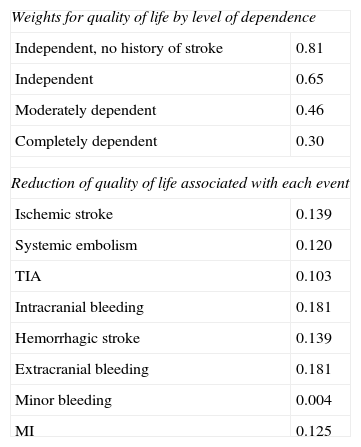

Quality of lifeThe estimation of QALYs associated with each option is based on the assumption that quality of life diminishes in the presence of disease and with the occurrence of events. Analysis of the initial quality of life of the study population and of the impact of events is thus essential.

For this purpose, we used the results of a meta-analysis20 of 20 studies estimating quality of life for stroke, and of one study that estimated utility values for various chronic diseases using a representative sample of the US population based on data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.21 The former was used to establish weights for levels of dependence after stroke, while the latter was used to evaluate the impact of events on quality of life (Table 2).

Quality of life.

| Weights for quality of life by level of dependence | |

| Independent, no history of stroke | 0.81 |

| Independent | 0.65 |

| Moderately dependent | 0.46 |

| Completely dependent | 0.30 |

| Reduction of quality of life associated with each event | |

| Ischemic stroke | 0.139 |

| Systemic embolism | 0.120 |

| TIA | 0.103 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 0.181 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 0.139 |

| Extracranial bleeding | 0.181 |

| Minor bleeding | 0.004 |

| MI | 0.125 |

MI: myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

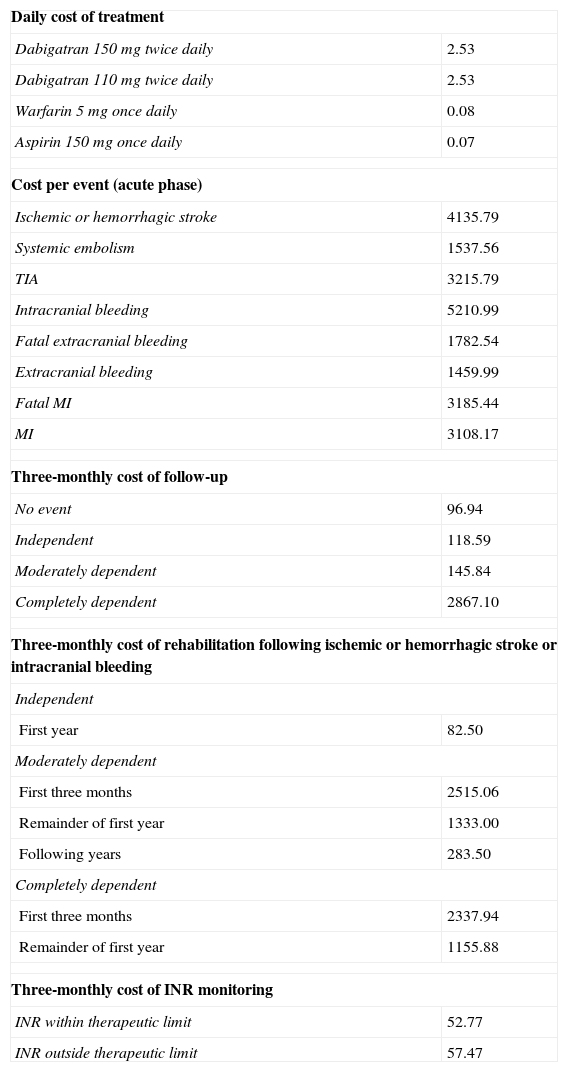

The resources consumed for treatment and follow-up of events were estimated on the basis of information provided by a panel of experts composed of six specialists with proven clinical experience (two cardiologists, two general clinicians and two neurologists).

Based on the resources identified by the panel, together with their respective unit costs22–24 (net of Value Added Tax [VAT]1), the costs incurred during acute treatment and follow-up were estimated. The cost of both doses of dabigatran (110 mg and 150 mg) are based on the recommended price of the patent-holding company. These are presented in Table 3.

Economic data (in euros).

| Daily cost of treatment | |

| Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily | 2.53 |

| Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily | 2.53 |

| Warfarin 5 mg once daily | 0.08 |

| Aspirin 150 mg once daily | 0.07 |

| Cost per event (acute phase) | |

| Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke | 4135.79 |

| Systemic embolism | 1537.56 |

| TIA | 3215.79 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 5210.99 |

| Fatal extracranial bleeding | 1782.54 |

| Extracranial bleeding | 1459.99 |

| Fatal MI | 3185.44 |

| MI | 3108.17 |

| Three-monthly cost of follow-up | |

| No event | 96.94 |

| Independent | 118.59 |

| Moderately dependent | 145.84 |

| Completely dependent | 2867.10 |

| Three-monthly cost of rehabilitation following ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or intracranial bleeding | |

| Independent | |

| First year | 82.50 |

| Moderately dependent | |

| First three months | 2515.06 |

| Remainder of first year | 1333.00 |

| Following years | 283.50 |

| Completely dependent | |

| First three months | 2337.94 |

| Remainder of first year | 1155.88 |

| Three-monthly cost of INR monitoring | |

| INR within therapeutic limit | 52.77 |

| INR outside therapeutic limit | 57.47 |

INR: international normalized ratio; MI: myocardial infarction.

The figures below were calculated from a societal perspective, considering overall costs, whether paid by the State or by patients. Costs accruing to the State were also estimated, taking a figure of 70% of the above figures for incremental costs and thus cost-effectiveness ratios, reflecting the fact that the State's contribution to the cost of dabigatran is 69%.

ResultsMain scenarioThe results naturally reflect the available clinical evidence. Dabigatran reduces the incidence of almost all the events considered, particularly ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, TIA, hemorrhagic stroke and intracranial bleeding, while it is associated with a higher incidence of MI and extracranial bleeding due to the greater risk in patients aged 80 or over taking 110 mg dabigatran.

The lower event rate is reflected in gains for patients medicated with dabigatran in terms of both life years and QALYs: 0.415 life years and 0.439 QALYs per patient when therapy begins before the age of 80, and 0.143 life years and 0.166 QALYs for therapy begun after the age of 80. Assuming that 69% of the population with AF is aged under 80,4 dabigatran confers mean gains of 0.331 life years and 0.354 QALYs.

The daily cost of dabigatran is higher than that of warfarin or aspirin. However, the cost of treatment and follow-up of patients after suffering an event reduces the incremental cost by 20–30%. The cost of such preventive therapy thus rises by 5572 euros for patients aged under 80 and 2300 euros for those aged 80 or over, a mean of 4558 euros; the net cost increases by 3763 euros, 1231 euros and 2978 euros, respectively.

Integrating the clinical and economic data enables the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) to be calculated per QALY and per life year (Table 4). Although there is no fixed willingness-to-pay threshold in Portugal per life year or QALY gained, the figure obtained – around 10000 euros per life year or QALY – is acceptable in the Portuguese context.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (in euros).

| Society | |||

| Age <80 | Age ≥80 | Mean | |

| Incremental cost (a) | 3763 | 1231 | 2978 |

| Incremental life years (b) | 0.415 | 0.143 | 0.331 |

| Incremental QALYs (c) | 0.439 | 0.166 | 0.354 |

| Cost per life year (a/b) | 9071 | 8592 | 9006 |

| Cost per QALY (a/c) | 8577 | 7420 | 8409 |

QALY: quality-adjusted life year.

All economic evaluations are based on hypotheses that are used to construct the main scenario. However, since these hypotheses can affect the results, it is important to analyze the effect of alternative values for the relevant parameters, usually through analysis of the sensitivity of the final result to the hypotheses adopted.

It should be borne in mind that there are two types of parameter: those that can be associated with a statistical distribution to reflect the level of uncertainty, such as the probability of the events under consideration; and those that cannot, such as discount rate or time horizon.

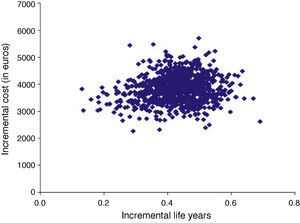

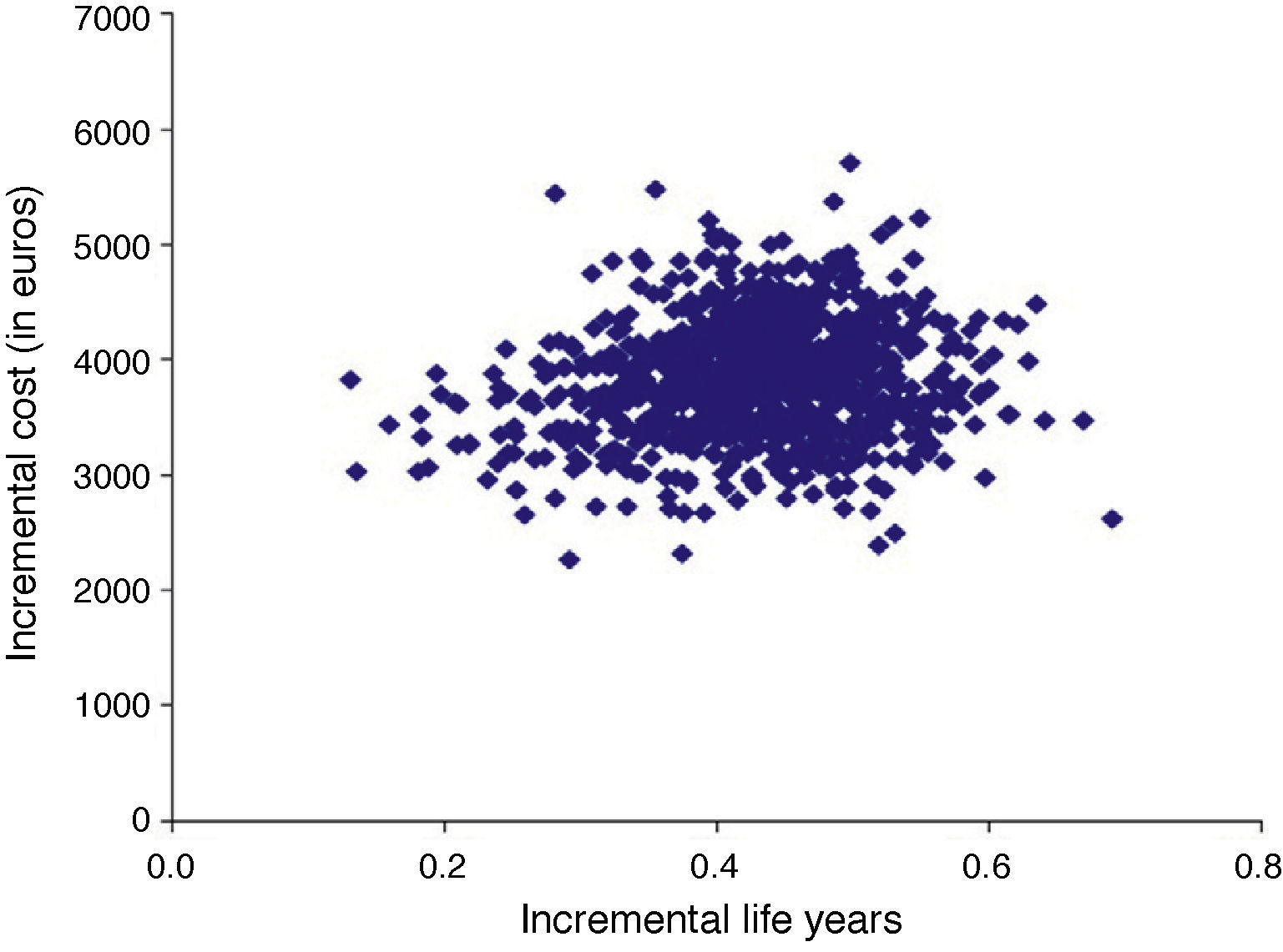

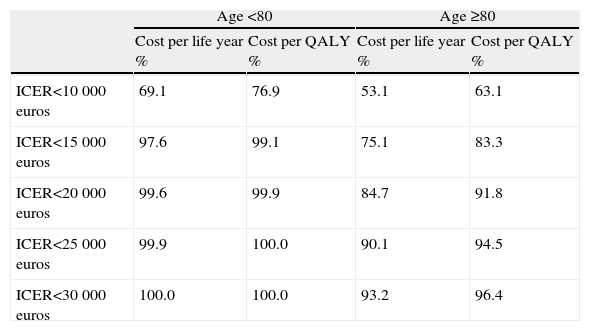

With regard to the first type, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis can be performed by simultaneously simulating different occurrence rates for the different parameters. By way of example, Figure 2 presents the incremental costs and life years from 1000 simulations of the population beginning therapy before the age of 80. One advantage of this type of sensitivity analysis is that the proportion of simulations in which the cost-effectiveness ratio is less than a particular willingness-to-pay threshold can be determined (Table 5). Based on the values usually taken as the willingness-to-pay threshold for health gains, the adoption of dabigatran is likely to be cost-effective: in almost all the 1000 simulations performed, dabigatran has an ICER of less than 15 000 euros, around half the threshold generally used in Portugal.

Distribution of simulations by incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

| Age <80 | Age ≥80 | |||

| Cost per life year % | Cost per QALY % | Cost per life year % | Cost per QALY % | |

| ICER<10 000 euros | 69.1 | 76.9 | 53.1 | 63.1 |

| ICER<15 000 euros | 97.6 | 99.1 | 75.1 | 83.3 |

| ICER<20 000 euros | 99.6 | 99.9 | 84.7 | 91.8 |

| ICER<25 000 euros | 99.9 | 100.0 | 90.1 | 94.5 |

| ICER<30 000 euros | 100.0 | 100.0 | 93.2 | 96.4 |

ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY: quality-adjusted life year.

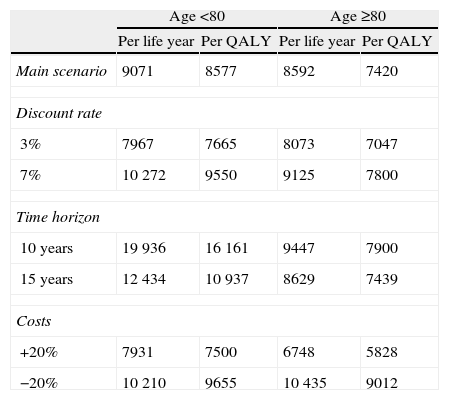

For the other parameters, a univariate sensitivity analysis is more useful, assessing the effect of different values in the main scenario. Table 6 presents the results for different discount rates, time horizons and costs. Both the discount rate (5%) and the time horizon (lifetime) used in the main scenario are those stipulated in the methodological guidelines in force in Portugal.25 However, while there is genuine uncertainty concerning the optimum value of the discount rate in this analysis, varying the time horizon merely reflects the time-frame during which the drug has an effect, since in methodological terms it is agreed that the differences between therapeutic options should be evaluated up to the time when these differences cease to exist, which in the case of chronic medication is the moment of death.

Univariate sensitivity analysis (in euros).

| Age <80 | Age ≥80 | |||

| Per life year | Per QALY | Per life year | Per QALY | |

| Main scenario | 9071 | 8577 | 8592 | 7420 |

| Discount rate | ||||

| 3% | 7967 | 7665 | 8073 | 7047 |

| 7% | 10 272 | 9550 | 9125 | 7800 |

| Time horizon | ||||

| 10 years | 19 936 | 16 161 | 9447 | 7900 |

| 15 years | 12 434 | 10 937 | 8629 | 7439 |

| Costs | ||||

| +20% | 7931 | 7500 | 6748 | 5828 |

| −20% | 10 210 | 9655 | 10 435 | 9012 |

QALY: quality-adjusted life year.

The costs of treatment and follow-up could theoretically be included in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. However, since they were estimated on the basis of figures agreed by an expert panel, univariate sensitivity analysis would seem to provide a better assessment of their effect on the final result.

The univariate analysis showed that none of the parameters considered, except the time horizon, had a significant effect on cost-effectiveness ratios, since altering these parameters resulted in variations of only around 10%. The larger impact of the time horizon is to be expected, as shorter periods would mean a significant proportion of dabigatran's health gains would be excluded; this is often the case in economic evaluations of preventive therapies. Naturally, given the shorter life expectancy of patients aged over 80, the impact of reducing the time horizon on results for this population is considerably less.

DiscussionFirstly, it should be pointed out that in this study a conservative approach was adopted, assuming that the efficacy of warfarin was that obtained as in the RE-LY trial. In reality, as control of INR values is fundamental in obtaining and maintaining the benefits of warfarin therapy and such control would tend to be easier to achieve under the conditions of a clinical trial, the effectiveness of warfarin in clinical practice is probably less than was assumed in this evaluation. The ability of warfarin to prevent stroke in clinical practice may be little more than half that estimated by clinical trials,26 mainly due to interactions with other drugs and with foods, the difficulty of monitoring INR, and bleeding risk.

Furthermore, the statistical power of the RE-LY trial has been reduced by the indications for use of dabigatran following approval by the European Medicines Agency, specifically the relation between age-group and daily dose. This is because all results for patients aged under 80 randomized to the 110 mg group, and for patients aged 80 or over randomized to the 150 mg group, are now irrelevant to this economic evaluation. As a result, some of the relative risks presented in Table 1 are not statistically significant. However, the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, which considers the entire statistical distribution of each relative risk, shows that the cost-effectiveness ratio is most likely below the maximum acceptable in the Portuguese context.

The sensitivity analyses performed show that the results are relatively robust to the uncertainty of the clinical data and of the estimates of costs in Portugal. It should be noted that a variation in costs of 20% would alter the ratios by around 15%.

Finally, comparison of the ratios for Portugal with those published for other countries in which an economic evaluation has been used to assist with decisions on funding for drugs (Canada16 and the United Kingdom17) shows that our results are conservative. The estimates of the cost of INR monitoring and, especially, the costs resulting from stroke, are lower in Portugal than in those two countries. As it is mainly in these parameters that dabigatran would reduce resource consumption, their lower levels would lead to higher cost-effectiveness ratios than those obtained in other countries.

ConclusionsThe results show that dabigatran is an important development for patients with non-valvular AF by reducing risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and intracranial bleeding, as well as their long-term sequelae. The expense of dabigatran is partially offset by lower event-related costs and by the fact that INR monitoring is unnecessary. It can thus be concluded on the basis of this economic evaluation that besides being an effective and safe treatment, as demonstrated by the RE-LY trial, dabigatran is a cost-effective therapeutic option for Portuguese AF patients.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Lda. The funding was paid directly to CISEP and was not conditional on obtaining any specific results.

Conflicts of interestThis study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Lda. The funding was paid directly to CISEP and was not conditional on obtaining any specific results.

The authors wish to thank the physicians who made up the expert panel: Aníbal Albuquerque, Armando Bordalo e Sá, Armando Brito de Sá, Elsa Azevedo, Vasco Queiroz, and Vítor Oliveira.

VAT should not be included in economic evaluations since it is merely a transfer between the payer and the State, and is thus not really a cost.

Please cite this article as: Silva Miguel L, Rocha E, Ferreira J. Avaliação económica do dabigatrano na prevenção de acidentes vasculares cerebrais isquémicos em doentes com fibrilhação auricular não valvular. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32:557–565.

TIA: transient ischemic attack.' title='Markov model. a History of stroke is modeled but not represented in the figure; b discontinuation due to minor bleeding. HS: hemorrhagic stroke; IB: intracranial bleeding; IS: ischemic stroke; MI: myocardial infarction;

TIA: transient ischemic attack.' title='Markov model. a History of stroke is modeled but not represented in the figure; b discontinuation due to minor bleeding. HS: hemorrhagic stroke; IB: intracranial bleeding; IS: ischemic stroke; MI: myocardial infarction;