In the last ten years there have been considerable improvements in imaging techniques in various areas and in cardiovascular imaging in particular. These advances have made diagnosis easier, but have also led to a dramatic increase in the use of diagnostic exams and hence a significant increase in health costs. In the USA, Medicare spending on diagnostic tests more than doubled between 2000 and 2006, while expenditure in the area of cardiology rose from $1.6 billion to $5.1 billion in 2006.1,2 These figures are giving rise to increasing concerns about the economic implications of this exponential growth, which will rapidly become financially and socially unsustainable. Reviews in the field of health economics show that the use of computed tomography (CT) increased three-fold, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) four-fold and ultrasound imaging by 70% between 1996 and 2010, while nuclear medicine studies decreased by a third from 2008 onward, possibly due to the increasing popularity of other techniques such as coronary CT angiography.3 The explosion in costs between 2000 and 2006 and its economic impact have been the subject of several studies that sought to determine the reasons behind this situation and to try and find a solution.2–4

Among the causes of most often put forward for these spiraling costs are the greater diagnostic ability of the new imaging techniques and their novelty value, patients’ growing awareness and demand for objective exams, fragmentation of care with duplication of testing, the practice of ‘defensive medicine’ and physicians’ lack of confidence in clinical assessment leading to a perceived need for confirmation from imaging studies, financial incentives for referring physicians, and demographic factors, especially aging populations.5–8

These studies focus on the USA and may not be directly applicable to other countries with different healthcare systems. However, certain factors merit further consideration, including the incessant need to confirm diagnoses as part of the growing practice of ‘defensive medicine’ based on intensive imaging, often the result of pressure from patients who have increasing access to online information (“Dr. Google”), wide media coverage of health-related subjects in recent years, and the growing number of medical malpractice lawsuits, especially in the USA. A 2008 study by the Massachusetts Medical Society showed that 22% of X-rays, 28% of CT scans, 27% of MRIs and 24% of ultrasound studies were performed for ‘defensive’ reasons.8

All of these factors explain why, according to one study, 20%–50% of advanced diagnostic imaging tests are of little or no benefit to the patient.9

In view of the need to rein in this growth by imposing limits, from both financial and medical standpoints, it became clear that appropriate use criteria were needed in order to provide some guidance to the medical community in terms of when to request diagnostic imaging studies.10,11 The intention was to avoid not only underutilization but also overutilization, which puts the patient at unnecessary risk, both directly by invasive techniques and indirectly due to radiation.12–14

An appropriate procedure was defined by Fitch et al. for the RAND Corporation as “one in which the expected health benefit (e.g., increased life expectancy, relief of pain, reduction in anxiety, improved functional capacity) exceeds the expected negative consequences (e.g., mortality, morbidity, anxiety, pain, time lost from work) by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing, exclusive of cost”,15 which can be summarized as “the right test for the right patient at the right time”.

Appropriate use criteria for echocardiography were published by the American College of Cardiology and the American Society of Echocardiography (ACC/ASE) in 200716 and revised in 2011.17 It should be borne in mind that these criteria were designed for the particular circumstances in the USA and have been adapted for use in other countries.18,19

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) are in the process of defining their own appropriate use criteria for echocardiography20 that are suited to the European context21 and that will weigh the costs and benefits of cardiovascular imaging in order to rationalize and optimize the available resources. Central to this process is the definition of what is and what is not appropriate, although there will be borderline cases that require further evidence before a decision is possible. The criteria will cover the following crucial points:

- -

the timing of initial and repeat tests for different conditions;

- -

prioritization of workload in imaging laboratories according to appropriate use criteria, improving scheduling and optimizing the organization of resources;

- -

standardization of results in order to avoid unnecessary repeat exams;

- -

control of costs and rationalization of resources.

A recent review analyzing changes in appropriate use of noninvasive cardiovascular imaging revealed marked improvements in appropriateness resulting from new appropriate use criteria in transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography and CT angiography but not in stress echocardiography.22

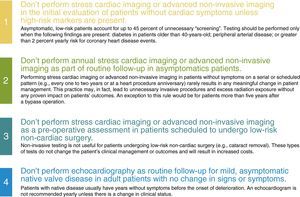

The Choosing Wisely online campaign, launched in 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in partnership with Consumer Reports, has the goal of advancing a national dialogue on avoiding wasteful or unnecessary medical tests, treatments and procedures. The ACC contributed four recommendations concerning cardiac imaging, including echocardiography.23,24 These recommendations are shown in Figure 1.

American College of Cardiology recommendations on the Choosing Wisely website.23

Little is known of the extent of this problem in Portugal, and so the study by Fonseca et al. in this issue of the Journal25 is a pioneering one. The authors reviewed requests for transthoracic echocardiographic exams over a randomly chosen period of one month in a tertiary care center.

The study's main limitation is that it reports the situation in a tertiary center, which cannot be extrapolated to other cardiology departments.

One important difference from other studies in the literature is that the proportion of inappropriate requests was higher among cardiologists than non-cardiologists. This may be due to the proximity of the echo lab and hence easy access for cardiologists; most exams (around 52%) were requested by cardiologists. The fact that experts in echocardiography were responsible for a similar percentage of inappropriate exams to less experienced cardiologists supports the idea that ease of access contributes to this finding.

In a single-center study by Ward et al. published in 2008, 89% of 1385 echocardiograms were considered appropriate and 11% inappropriate; only 40% of appropriate exams and 17% of inappropriate exams revealed new major echocardiographic abnormalities. Non-cardiac specialists ordered more inappropriate studies than cardiac specialists (13% vs. 9%, p<0.001).26

In a study in Italy by Latanzi et al., the authors reviewed the indications for echocardiography in 2848 patients and concluded that about half of requests could be considered inappropriate, with 23.1% of non-cardiologists’ requests being inappropriate, 37% appropriate and 39.9% of doubtful appropriateness, as opposed to 11.4%, 58.8% and 29.8%, respectively, among cardiologists.27

The fact that inappropriate exams were more common in outpatients than in inpatients in the study by Fonseca et al. is understandable, since hospitalization constitutes preselection of the patient.

Residents were slightly more likely than specialists to request inappropriate exams, which may be due to the practice of ‘defensive medicine’ and relative lack of experience, both factors mentioned in the literature.28,29

Some echocardiographic exams were considered unclassifiable according to the 2011 ACC/ASE criteria, many of them before or after invasive procedures such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation or left atrial appendage closure, which are increasingly common and will be covered in future revisions of the criteria. The EACVI criteria are awaited.

Although the subject is not part of medical training, it is essential to teach the concept of appropriate use and to increase awareness of its importance,30 since only in this way can resources be optimized by avoiding unnecessary and expensive diagnostic exams that may carry risks for the patient and that consume time and resources with no apparent improvement in medical outcomes.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Galrinho A. Comentário a critérios de adequação para ecocardiografia transtorácica num centro terciário. Rev Port Cardiol. 2015;34:719–722.