Current epidemiological data on heart failure (HF) in Portugal derives from studies conducted two decades ago. The main aim of this study is to determine HF prevalence in the Portuguese population. Using current standards, this manuscript aims to describe the methodology and research protocol applied.

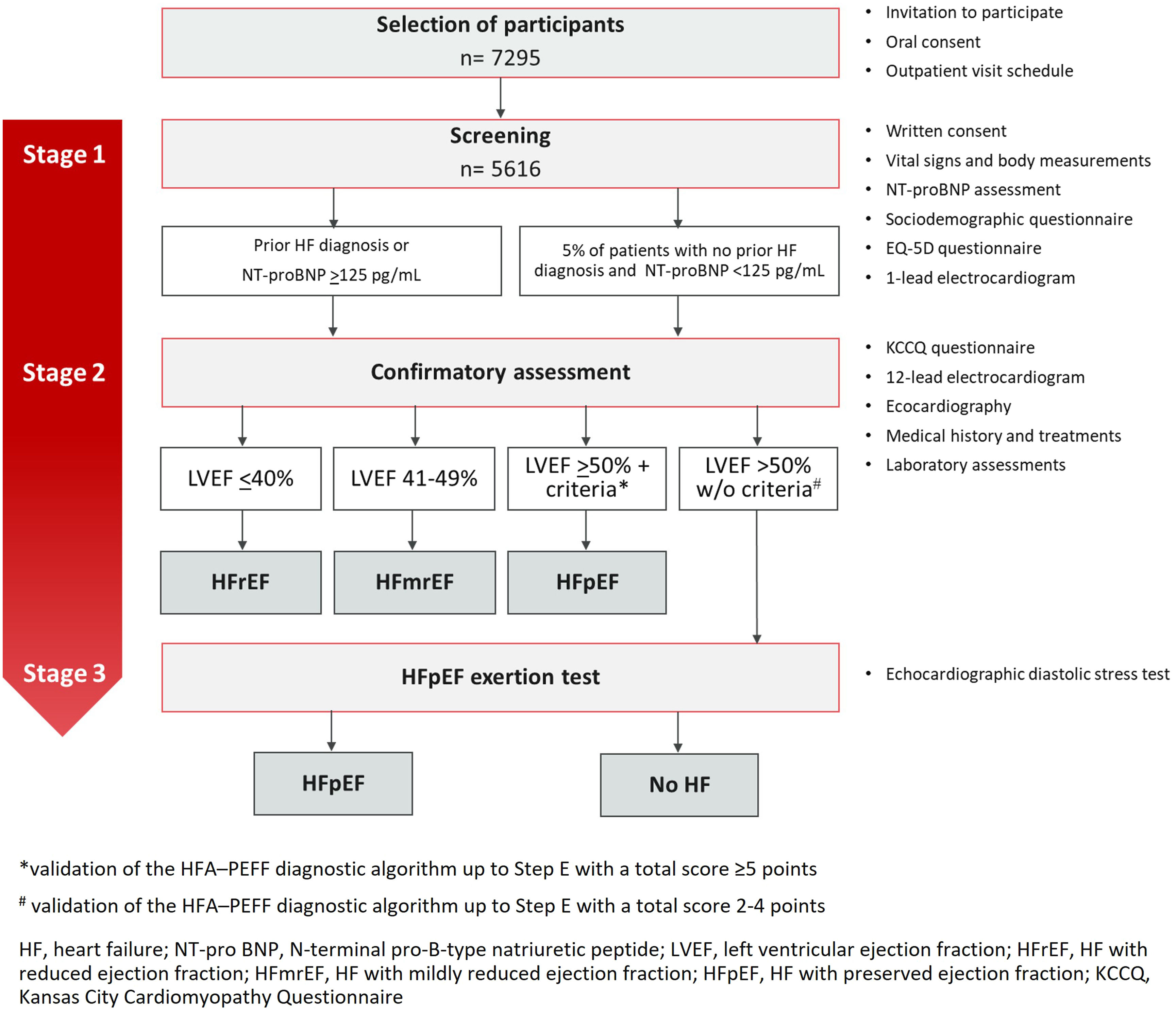

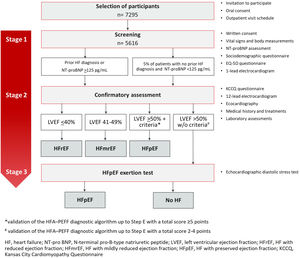

MethodsThe Portuguese Heart Failure Prevalence Observational Study (PORTHOS) is a large, three-stage, population-based, nationwide, cross-sectional study. Community-dwelling citizens aged 50 years and older will be randomly selected via stratified multistage sampling. Eligible participants will be invited to attend a screening visit at a mobile clinic for HF symptom assessment, anthropomorphic assessment, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) testing, one-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and a sociodemographic and health-related quality of life questionnaire (EQ-5D). All subjects with NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL or with a prior history of HF will undergo a diagnostic confirmatory assessment at the mobile clinic composed of a 12-lead ECG, comprehensive echocardiography, HF questionnaire (KCCQ) and blood sampling. To validate the screening procedure, a control group will undergo the same diagnostic assessment. Echocardiography results will be centrally validated, and HF diagnosis will be established according to the European Society of Cardiology HF guidelines. A random subsample of patients with an equivocal HF with preserved ejection fraction diagnosis based on the application of the Heart Failure Association preserved ejection fraction diagnostic algorithm will be invited to undergo an exercise echocardiography.

ConclusionsThrough the application of current standards, appropriate methodologies, and a strong research protocol, the PORTHOS study will determine the prevalence of HF in mainland Portugal and enable a comprehensive characterization of HF patients, leading to a better understanding of their clinical profile and health-related quality of life.

Os dados epidemiológicos atuais sobre insuficiência cardíaca (IC) em Portugal provêm de estudos realizados há mais de duas décadas. O objetivo principal deste estudo é determinar a prevalência da síndrome de IC na população portuguesa com 50 ou mais anos, sendo, especificamente, objetivo deste artigo descrever as abordagens metodológicas e o protocolo de investigação aplicados.

MétodosO Estudo de Prevalência de Insuficiência Cardíaca em Portugal (PORTHOS) é um estudo observacional transversal de grande dimensão, de base populacional, nacional, constituído por três fases. Serão selecionados aleatoriamente por amostragem estratificada multietapas cidadãos com 50 ou mais anos residentes na comunidade em Portugal. Os participantes elegíveis serão convidados a participar numa visita de triagem, que decorrerá numa clínica móvel, durante a qual serão submetidos a avaliação de sintomas de IC, avaliação antropomórfica, um teste de N-terminal pró-peptídeo natriurético tipo B (NT-proBNP), eletrocardiograma de 1 derivação, questionários sociodemográficos e questionário de qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde (EQ-5D). Todos os participantes com NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL ou história prévia de IC serão submetidos a uma avaliação diagnóstica confirmatória composta por eletrocardiograma de 12 derivações, ecocardiografia completa, questionário de IC (KCCQ) e colheita de sangue. Para validar o procedimento de triagem, um grupo controlo passará pela mesma avaliação diagnóstica. Os resultados dos ecocardiogramas realizados serão validados centralmente e o diagnóstico de IC será confirmado de acordo com as recomendações de IC da Sociedade Europeia de Cardiologia. Uma subamostra aleatória de participantes com diagnóstico questionável de IC com fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEp), após a aplicação do algoritmo de diagnóstico de fração de ejeção preservada da Heart Failure Association (HFA-PEFF) será convidada a realizar ecocardiografia de esforço.

ConclusãoAtravés da aplicação das recomendações atuais e abordagens metodológicas adequadas, o estudo PORTHOS irá determinar a prevalência da IC em Portugal Continental e permitir uma caracterização abrangente dos doentes com IC, para melhor compreensão do seu perfil clínico e qualidade de vida relacionada com a saúde.

Heart failure (HF) is one of the major chronic health conditions worldwide, causing considerable healthcare-related costs and imposing an important burden on patients, national health services, and society.1–3 While the survival of HF patients has gradually improved over the last decades, its prevalence and incidence are steadily increasing.2 Although HF is common in clinical practice, contemporary data on its epidemiology is lacking in many European countries. Therefore, precise information on the prevalence and the characterization of this syndrome are warranted for the development of health policies designed to mitigate the impact of HF.

The prevalence of HF is estimated to be 1–2% among adults in industrialized countries, with an incidence of 1–10 per 1000 persons per year.4 As a syndrome associated with aging, HF is uncommon among those below 50 years of age, but increases steadily in elderly patients.5,6 A 2022 meta-analysis estimated a symptomatic HF prevalence of 8.3% among those above 50 years old.7 The 2021 European Society of Cardiology – Heart Failure Association (ESC-HFA) Atlas reported a median HF prevalence of 17.20 cases per 1000 people, ranging from less than 12 in Greece and Spain, to more than 30 in Lithuania and Germany. However, Portugal was not included in this prevalence analysis.8 Due to an increasingly older population, a higher HF prevalence has been estimated in our country.2,9

Previous efforts have been made to evaluate HF burden in Portugal, but mostly focused on selected populations. The pivotal EPICA5 (1998) and EPICA-RAM6 (2001) used a combination of clinical and echocardiographic indices based on the 1995 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis of chronic HF and estimated global HF prevalence at 4.4% and 4.7% respectively. They demonstrated a steep age-related increase in prevalence. Also, during the early 2000s, a regional health survey conducted in Porto estimated that HF prevalence was 7.2% in those over 45 years.10 In a recent meta-analysis, based on these data, Portugal had one of the highest HF prevalence reported among 11 countries.7

Recently, two non-interventional cross-sectional studies using data from electronic healthcare records, also performed in the Northern region of Portugal (Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos), were published.11,12 HF prevalence was estimated as 2.9% by considering all patients with an electronic diagnosis of HF in both primary care and hospital settings. When a more stringent definition was applied to the same dataset, using echocardiographic parameters and elevated natriuretic peptides cut-off levels from recent HF trials, the estimated prevalence was in 2.1%11 in those over 18 years of age.11

No previous population-based studies in Portugal have used the current HF definition and classification system nor used contemporary diagnostic procedures, such as natriuretic peptides or advanced echocardiographic parameters, as recommended by the ESC guidelines.13,14 Therefore, the actual prevalence of HF in Portugal and the impact of this syndrome are largely unknown. Additionally, the impact of HF on health-related quality of life13,15 is also unknown in our country.

Thus, the Portuguese Heart Failure Prevalence Observational Study (PORTHOS) aims to determine HF prevalence among those aged 50 years and older in mainland Portugal, by using a contemporary and guideline-based diagnostic approach, including self-reported symptoms, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and comprehensive echocardiographic data.

MethodsStudy designPORTHOS is a population-based cross-sectional prevalence study. It will be conducted among a representative sample of mainland Portugal population aged 50 years or above, geographically distributed across five administrative health regions (ARS): North, Center, Lisbon and Tagus Valley, Alentejo, and Algarve.

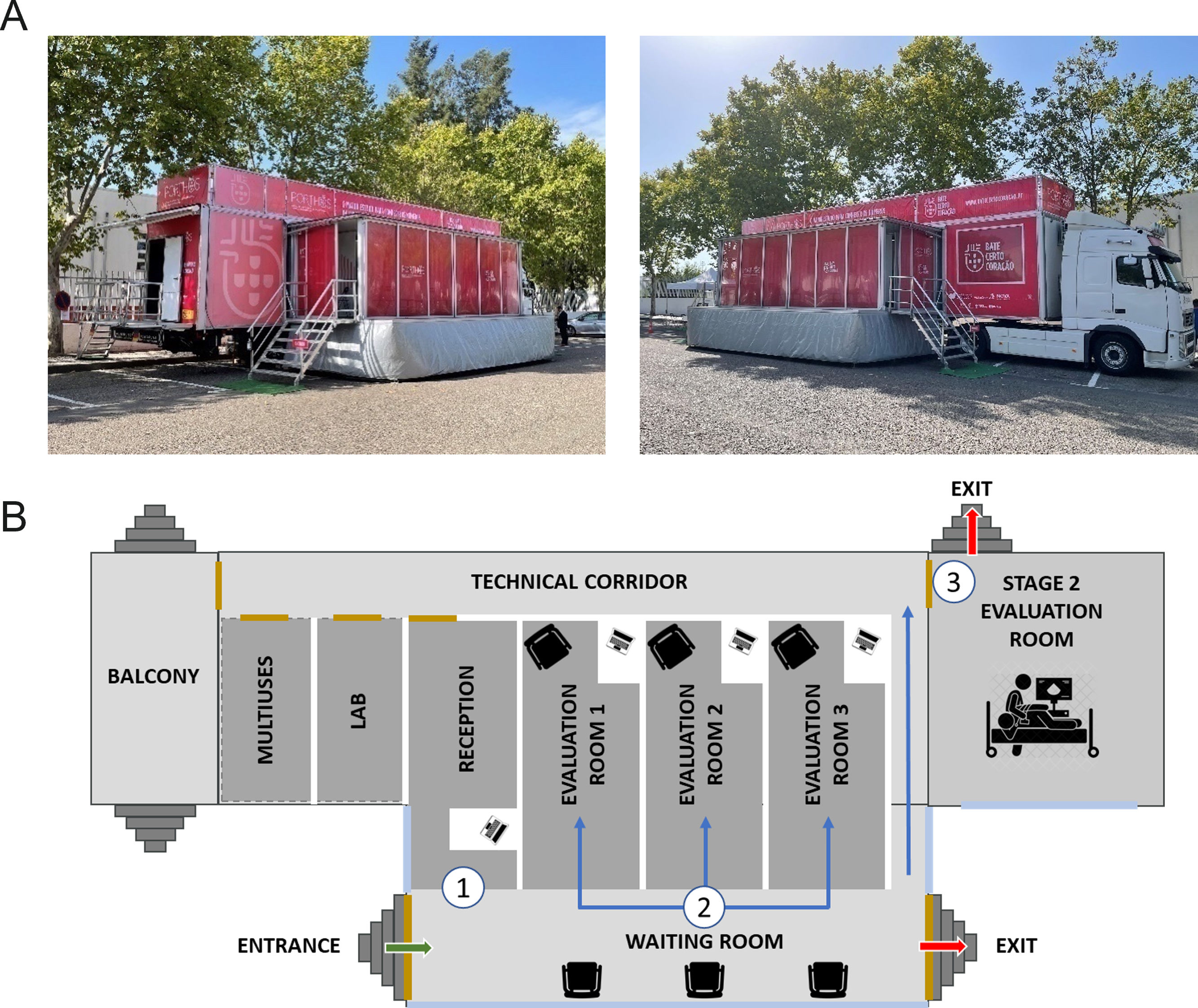

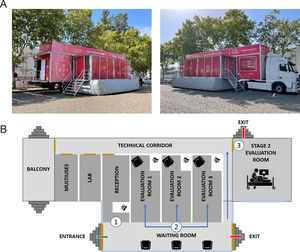

The study implementation will start in the region where approval is first obtained from the competent ethics committee. It will proceed sequentially as the remaining approvals are received. The study uses a three-stage approach design, parallel to the recommended clinical diagnostic methodology.13 Eligible participants will be randomly invited by telephone. They will perform the study assessments in a mobile outpatient clinic with all the guideline-recommended diagnostic tools available onsite (Figure 1). A subset of participants with suspected HF but a non-diagnostic echocardiogram will be invited for additional hospital-based assessments. The present study protocol is described according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies (STROBE)16 and has the clinicaltrials.gov trial registration number NCT05434923.

Study population and sample sizeStudy populationCommunity-dwelling adults aged 50 years or above, living in mainland Portugal, will be included in the study. Participants will be selected through a multistage sampling methodology, using the National Health Service (SNS) registry as the sampling frame. In the first stage, geographical areas will be selected, while in the second stage individuals will be sampled within each selected area. Within each of five health regions (ARS) that comprise mainland Portugal, primary sampling units (PSU) will be defined as geographical areas corresponding to Primary Care Centers Groups (ACES). Of the 55 ACES in Portugal, 12 PSU will be selected considering their rural (<100 people per km2), semi-urban (100–500 people per km2) or urban (>500 people per km2) characteristics. The number of PSU to be selected by region will be proportional to the size of resident population aged 50 years or above. PSU will be selected within each ARS region by simple random sampling without replacement using the “sampling” package of R statistical software. At the second stage, subjects aged 50 years old or over registered in the primary care units will be stratified by age and gender and selected randomly.

As more than 99.0% of the Portuguese population is registered at a community health care center, the SNS database is considered representative of the total resident population. Randomly selected individuals will be invited to participate in the study in a telephone call made by trained SNS personnel and eligibility criteria will be applied. An authorization for using their personal data will be obtained. A semi-structured interview guide and form will be followed, including a summary of the study procedures and eligibility criteria.

Study exclusion criteria include:

- (a)

living in an institution (e.g., nursing homes, prisons, military facilities)

- (b)

being unable to speak and understand Portuguese

- (c)

having reduced physical and/or cognitive abilities hampering study participation (e.g., blindness, deafness, or cognitive impairment).

Five telephone call attempts will be made before a subject is considered as an invitation failure. A screening log of potential eligible participants will be established to document the reasons for declining participation. At least 15000 telephone calls will be made to secure 7295 eligible participants, predicting a 50% non-acceptance/contact failure rate on invitation. Contacts will be made sequentially and according to a random list stratified by sex and age, until the defined number of participants in each geographic region is reached. After agreeing to participate, the participant's visit to the mobile outpatient clinic will be scheduled.

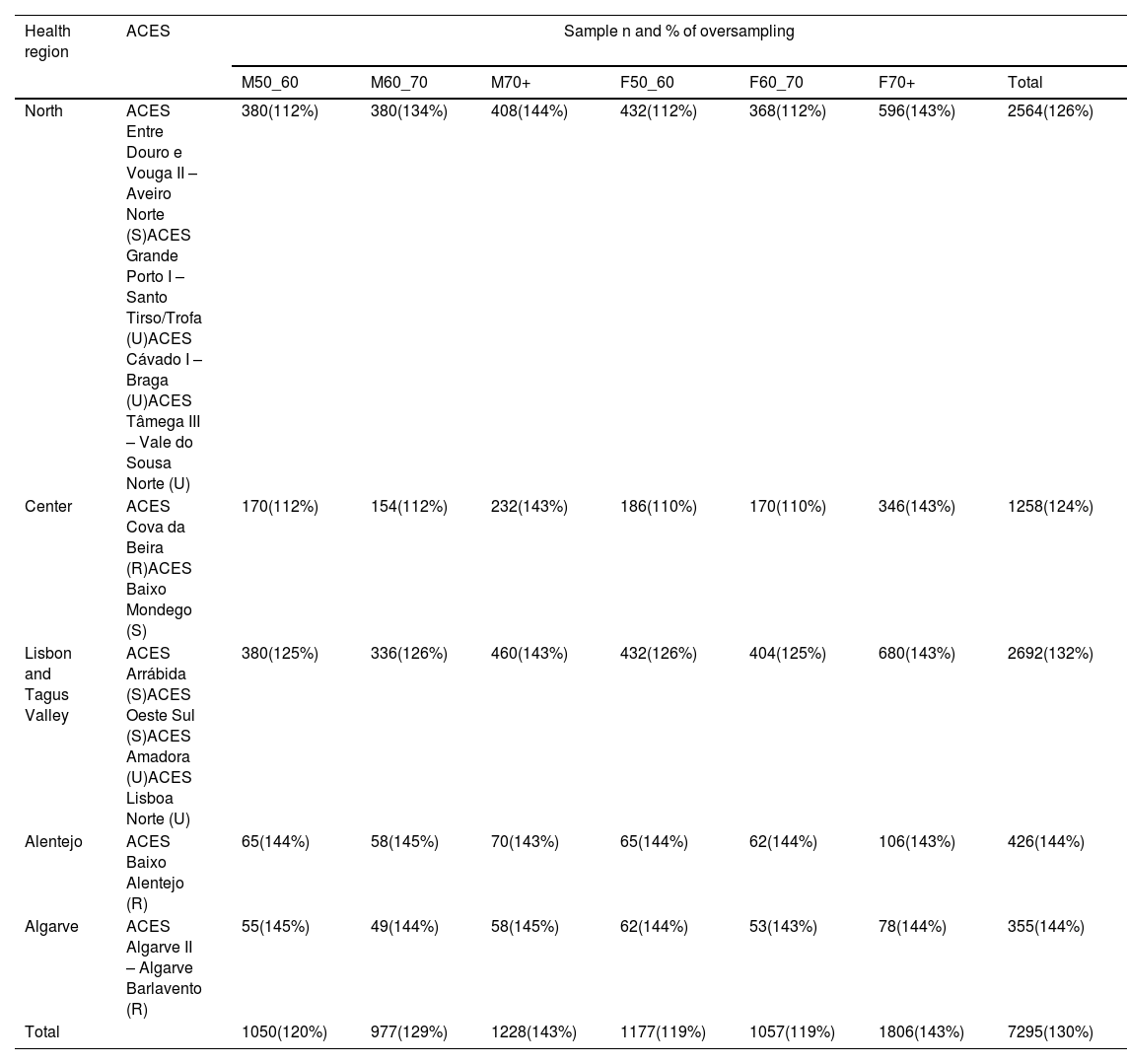

Sample sizeSample size calculation was based on the expected prevalence of HF of 2.5%, with an absolute precision of 0.5% and design effect of 1.5 to account for clustering. The design effect (Deff) is a correlation factor that is used to adjust the required sample size for cluster sampling. The required sample size, assuming a simple random sample (SRS), should be calculated, and then multiplied by the Deff. In this case, a design effect of 1.5 means that the variance of the clustered sample is 1.5 times larger than the variance of a simple random sample of the same size. Nationally, a total sample size of 5616 individuals was computed. To account for sampling frame imperfections and expected participation rates of 40–90%, oversampling will be performed and a total of 7295 eligible participants will be required. Effective sample size for each region–age–sex group was computed as n/PR, where PR is expected participation rate and n is a sample size computed in the first step (Table 1). Oversampling factors were defined by region and age group according to participation rates reported in Portugal by previous surveys that have used similar sampling methodology.5,6,17,18

Selected ACES and proportional selected sample with oversampling.

| Health region | ACES | Sample n and % of oversampling | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M50_60 | M60_70 | M70+ | F50_60 | F60_70 | F70+ | Total | ||

| North | ACES Entre Douro e Vouga II – Aveiro Norte (S)ACES Grande Porto I – Santo Tirso/Trofa (U)ACES Cávado I – Braga (U)ACES Tâmega III – Vale do Sousa Norte (U) | 380(112%) | 380(134%) | 408(144%) | 432(112%) | 368(112%) | 596(143%) | 2564(126%) |

| Center | ACES Cova da Beira (R)ACES Baixo Mondego (S) | 170(112%) | 154(112%) | 232(143%) | 186(110%) | 170(110%) | 346(143%) | 1258(124%) |

| Lisbon and Tagus Valley | ACES Arrábida (S)ACES Oeste Sul (S)ACES Amadora (U)ACES Lisboa Norte (U) | 380(125%) | 336(126%) | 460(143%) | 432(126%) | 404(125%) | 680(143%) | 2692(132%) |

| Alentejo | ACES Baixo Alentejo (R) | 65(144%) | 58(145%) | 70(143%) | 65(144%) | 62(144%) | 106(143%) | 426(144%) |

| Algarve | ACES Algarve II – Algarve Barlavento (R) | 55(145%) | 49(144%) | 58(145%) | 62(144%) | 53(143%) | 78(144%) | 355(144%) |

| Total | 1050(120%) | 977(129%) | 1228(143%) | 1177(119%) | 1057(119%) | 1806(143%) | 7295(130%) | |

ACES: Agrupamentos de Centros de Saúde (primary care centers groupings); F: female; M: male; R: rural; S: semi-urban; U: urban.

All procedures will be carried out at a mobile unit designed to comply with the assessments’ safety requirements and their specific conditions (Figure 1). They will be performed in a three-stage stepwise approach (Figure 2).

Stage 1 – screeningAt the mobile outpatient clinic, a study number will be assigned to each participant. Following the explanation of the study procedures, participants will be asked to sign the study informed consent. A specific, additional, and optional, informed consent for the preservation and storage of blood and plasma samples in a biobank will also be signed if agreed by the participant. All participants will be asked regarding a prior diagnosis of HF. A peripheral blood sample will be obtained to measure the NT-proBNP level through point-of-care testing methods (Roche Diagnostics®). This blood sample will also be used for further plasma or serum assessments if the participant proceeds to Stage 2. Participants will be asked to complete a sociodemographic and an EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. The EQ-5D is a generic tool for use as a measure health outcome allowing for the calculation of a single index value for health status.19 Height, weight, and waist circumference will be measured, as well as vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate) and blood oxygen saturation. A one-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) will also be performed (MyDiagnostick®), aiming for atrial fibrillation (AF) screening.

Participants will be invited to proceed to the Stage 2 evaluation if NT-proBNP is ≥125 pg/mL, or if they self-report a prior HF diagnosis. If NT-proBNP is <125 pg/mL and there is no prior HF diagnosis, study participation ends. Nevertheless, as a quality control measure, a random sample of this group will also participate in Stage 2 (∼5% of patients with NT-proBNP <125 pg/mL and no prior history of HF). The control sub-group will be recruited sequentially (one participant for every 20 participants).

Where AF is suspected on the one-lead ECG but requirements are not met to proceed to Stage 2, the participant will be invited to perform a 12-lead ECG for AF confirmation at the same visit. In case of a confirmatory ECG, a report will be issued and given to the participant for general practitioner (GP) referral.

Stage 2 – confirmatory assessmentParticipants qualified to advance to Stage 2 will complete: (1) a structured questionnaire; (2) the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)20; (3) a 12-lead ECG; (4) a complete transthoracic echocardiography; and (5) laboratory assessments:

- (1)

The structured questionnaire will be administered by a trained non-medical interviewer, using a standardized, computer-assisted personal system in order to obtain information on participant medical history, symptoms, and drug therapy.

- (2)

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) will be completed directly by the study participant using a tablet. The KCCQ is a self-administered, 23-item questionnaire developed to provide a better description of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic HF.20

- (3)

A standard 12-lead ECG will be recorded by a trained professional using a laptop electrocardiograph (NORAV Medical ECG®) in supine position. It will be digitally stored and will be analyzed using a standardized and validated ECG software program.

- (4)

A complete transthoracic echocardiogram will be performed by a trained sonographer, using the European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) methodology, according to the 2015 chamber quantification and the 2016 diastolic function recommendations.21,22 The images will be stored and analyzed offline in the EchoPac® General Electric® by an EACVI-certified cardiologist. According to the recommendations of the ESC, systolic function will be considered as preserved if left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is ≥50%, mildly reduced if between 41% and 49% and reduced if ≤40%.13 LVEF will be determined from the apical four-chamber and two-chamber views and calculated according to the Simpson disk-summation method. Diastolic function will be determined based on the following parameters: ratio of peak early (E) to peak atrial (A) Doppler mitral valve flow velocity (E/A), deceleration time (DT), left atrial volume index (LAVI), the sex-specific left ventricular mass index (LVMI), tissue-doppler imaging of the septal and lateral mitral annulus (e′) and tricuspid regurgitation velocity (VTR), according to the EACVI/ASE international guidelines.23

- (5)

Finally, several blood parameters will be determined for participants that complete Stage 2, namely HbA1c, serum creatinine, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, and high-sensitive troponin T, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and NT-proBNP levels. Samples will be stored at 4°C and sent daily to the central laboratory and biobank. Study samples will be discharged at study end and biobank samples (serum, plasma, deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] and ribonucleic acid [RNA] aliquots) will be stored. The diagnosis of HF will be established as per the 2021 ESC HF guidelines.13

We will follow the 2021 Universal Definition of Heart Failure for case ascertainment, taking in consideration (i) self-reported symptoms and (ii) an objective measurement of congestion, in the case, natriuretic peptides,24 as proposed. Therefore, participants with self-reported fatigue or shortness of breath New York Heart Association ≥II (assessed by a structured questionnaire) or self-reported orthopnea or self-reported edema, a NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL and a LVEF ≤40% will be classified as HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Participants with self-reported symptoms, a NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL and a LVEF between 41% and 49% will be classified as patients with HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF). Finally, all participants with self-reported symptoms, a NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL, a LVEF ≥50% and validating the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm14 up to Step E with a total score ≥5 points are considered to have a diagnosis of HFpEF. A total score ≤1 point is considered as not supporting the diagnosis of HFpEF and an intermediate score (2–4 points) as indeterminate diagnosis and hence, will not be considered as HFpEF. The evaluation of valvular heart disease as a specific cause of HFpEF syndrome will also be assessed in a predefined secondary analysis considering data obtained from comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation.

Patients will be classified as pre-HF (stage B) if NT-proBNP is elevated (≥125 pg/mL) without current or prior symptoms of HF but evidence of (i) structural heart disease (e.g. left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac chamber enlargement, ventricular wall motion abnormality or moderate to severe valvular heart disease) or (ii) abnormal cardiac function (reduced left or right ventricular systolic function, evidence of increased filling pressures or abnormal diastolic dysfunction).

Stage 3 – HFpEF exertion testingThe diagnostic algorithm HFA-PEFF, including echocardiographic data and NT-proBNP levels, will be applied.14 We estimate that around 30% of the participants will meet the criteria for further workup (self-reported HF symptoms and signs, NTpro-BNP ≥125 pg/mL, LVEF ≥50% but not validating the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm up to Step E).25 Therefore, a random sample of participants scoring 2–4 points will be recruited and invited sequentially to perform the exercise echocardiogram (diastolic stress test) in a reference hospital. In this case, patients will be asked to exercise on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer until maximally tolerated fatigue, or until they reach the maximal expected heart rate. Workload will be increased by 25 Watts every 2 min. Echocardiographic measurements will be taken during the last minute of each workload step. Cardiac output, pulmonary pressure, and E/e′ will be calculated as previously reported. The cut-off values recommended in the HFA consensus document on HFpEF diagnosis will be used and those with an abnormal test will be classified as having HFpEF.14

Data collectionData will be collated into an electronic case report form (eCRF) specifically designed for the PORTHOS study (Infortucano, Lda.). Data will be extracted from the computer-assisted personal interviews and the complementary examinations performed by the study team. Data collection will be performed under a confidentiality agreement and the supervision of the study Principal Investigators. Study data will be stored at the National Centre of Cardiology Data Collection of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. Biological samples will be sent to a centralized laboratory (UNILABS) and biobank samples will be processed and sent to the biobank at the Centro Académico Clínico de Coimbra: Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra – University of Coimbra (CACC CHUC – UC).

Pilot studyThe PORTHOS pilot study was performed in December 2021 in a local health unit located in the North region of the country (Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos) with the objective of testing the study workflow and identifying implementation risks to mitigate prior to the study initiation. Logistical issues were also evaluated, including the functionality and usability of the eCRF. The conclusions of the pilot study led to the study protocol being improved.

Ethical considerationsThe PORTHOS study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical recommendations for health research involving human participants, Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP), International Council for Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) and the applicable Portuguese legislation. The study protocol and the informed consent form will need to be approved by each ARS Ethics Committee before study implementation. Verbal and written informed consent will be obtained prior to subject participation. Two written consents will be required, an informed consent form for the PORTHOS study procedures and another independent and specific form for blood sample storage in a biobank. Participants can voluntarily withdraw or discontinue their study participation at any stage, without any implication for their health care. Subjects who discontinue will be asked for the reason(s) for their discontinuation. Data protection will be assured by pseudonymization and encryption process, which keeps the confidentiality and anonymity of each study participant. For participants for whom a diagnosis of HF is suspected or that have a relevant finding in the analytical or cardiac exams, a report will be issued for appropriate follow-up by primary care physicians and referral for hospital consultation.

Statistical analysisThe prevalence estimates for symptomatic HF and other heart related conditions will be computed as weighted proportions, considering the sampling design. The extrapolation weights will be calculated as the inverse of the inclusion probabilities of the stratified cluster design. The stratification is based on the five NUTS II regions, the twelve selected ACES and populational density associated to each ACES (<100; 100–500; >500 inhabitants per km2). These weights will then be submitted to a calibration process by crossing region (five classes), ACES population density, gender, age stratum and non-response.

A descriptive analysis of the data will be performed, including a characterization of the study population regarding sociodemographic and health-related variables. Categorical variables will be presented as absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables as mean, standard deviations, and range. To compare individuals with and without HF a univariate analysis will be performed. To assess which factors are associated with the presence of HF, univariable and multivariable logistic regression models will be applied.

To assess the burden of the disease on health-related quality of life, we will use linear regression. The assessment will be performed using KCCQ and EQ-5D-5L. Association between biomarkers of interest and HF prevalence will be explored through Student's t test for independent samples or correspondent nonparametric test. The association with the severity of HF will be explored using Spearman correlation coefficient. Imputation methods will not be used to deal with missing data. All analyses will be performed considering a level of significance of 0.05. The statistical package SPSS® (IBM, USA) will be used to conduct the statistical analyses.

DiscussionPrevious efforts to describe the prevalence of HF comprehensively have been made worldwide. In a recently published systematic review, the average reported HF prevalence in adults was 3.4%, and varied widely across locations.7 Among the 22 studies reporting HF prevalence in adults, three were from Portugal, including the EPICA,5 EPICA-RAM6 and EPI-PORTO10 studies. It was worthy of note that all three reported a high HF prevalence, ranking among the top-5 highest in the aforementioned review.7 In fact, 20 years ago the pivotal EPICA study estimated a 4.36% HF global prevalence in mainland Portugal.5 This estimate was high, taking into consideration other international epidemiological studies conducted at that time, but as it included not only HFrEF patients, but also diastolic heart failure (DHF), valvular HF and right HF patients, it was an estimate of the global HF prevalence and not only HFrEF, as was common practice in other contemporary studies. When compared with other studies also conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000s that assessed DHF, EPICA reported a prevalence of this phenotype in the range of other reports (2.6–8.8%). A similar HF prevalence was subsequently reproduced in a different population in the EPICA-RAM, a sub-study of EPICA in the Autonomous Regions of Madeira, estimating a HF prevalence of 4.69%.6 Additionally, in both studies, a sharp increase in HF prevalence observed with age, ranging from 1.36% in the group between 25 and 49 years old to 16.15% in those over 80.5,6 Although the age-specific burden of HF in the Portuguese population may play a role in the higher estimate of HF prevalence, compared to other countries,7 variations in study design, demographic breakdown and case ascertainment strategy cannot be ruled out as factors contributing to the observed difference.

All these analyses were conducted between the late 1990s and early 2000s, well before the development of natriuretic peptides for the diagnosis of HF and the dissemination of advanced echocardiographic techniques for the assessment of diastolic function and left ventricular filling pressures. On the other hand, changes in population composition due to aging, the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, changes in social determinants, and improvements in the management of acute coronary syndromes and other acute cardiac conditions may all have different and possibly divergent effects in HF prevalence.

In addition, when compared to PORTHOS, a few methodological differences are worthy of mention, mainly due to historical reasons. In the cross-sectional EPICA5 and EPICA-RAM6 studies, the sampled population consisted of subjects attending primary care centers in the community instead of the general population. The population followed by GPs might not be representative of the general population, therefore a selection bias cannot be ruled out.26 Besides, the definition of cases relied on physicians’ recognition of the syndrome, based on the Boston questionnaire score, and echocardiographic evidence of cardiac abnormalities. The eligibility echocardiogram was locally sourced, making it very challenging to evaluate LV ejection fraction or Doppler parameters. Therefore, LV systolic dysfunction was defined as (i) a fractional shortening below 28% or (ii) severe wall motion abnormalities with LV dilation impairing systolic function, regardless of the fractional shortening measured by echocardiogram. Diastolic function was assessed using morphological parameters, as was the standard practice at the time.

In order to leverage all the diagnostic advances obtained during the 21st century, the PORTHOS study will determine the prevalence of HF using a comprehensive multistage, and stepwise approach, combining self-reported symptoms, point-of-care natriuretic peptides quantification and a centralized, comprehensive echocardiographic examination according to the recently published 2021 ESC HF guidelines criteria.13 Additionally, the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm14 will be also applied in a specific cohort of patients, which will give important data on the applicability of this HFA/ESC proposed algorithm in real-world evidence studies. In addition to HF prevalence determination, PORTHOS will comprehensively characterize patients’ age and gender-specific prevalence, along with stratification by HF phenotypes. Additionally, it will be also possible to evaluate asymptomatic LV dysfunction prevalence in patients with NT-proBNP ≥125 pg/mL, as all participants in previous studies were required to have HF symptoms (reported through a questionnaire). The design of PORTHOS will profile a detailed view through the continuum of HF burden in both clinical and sub-clinical HF stages. PORTHOS will also enable the evaluation of the prevalence of comorbidities and/or CV risk factors among HF patients, as well as their clinical impact. This study will also be able to assess and describe throughly the health-related quality of life in the HF population (overall and for different phenotypes and severity levels), as the EQ-5D and KCCQ questionaries will be used. Importantly, more information is warranted on whether socioeconomic factors play a significant role in HF clinical and symptomatic burden. With future research in mind, the PORTHOS biobank will enable the identification of new markers for early diagnosis or for prognostic evaluation, which may lead to significant changes in health policies on patient screening, diagnosis, and management. The informed consent includes an authorization for further contact, which would enable follow-up studies. Finally, the collection of a one-lead ECG in all PORTHOS participants will enable the estimation of AF prevalence in the population aged over 50 years.

Sampling assumptions were based on population density, sex and age strata and considered the participation rates reported in Portugal by previous surveys that have used similar sampling methodologies to increase the robustness and representativeness of the estimates. Indeed, one of PORTHOS'strengths is the fact that its methodology is aligned not only with other previous successful epidemiological studies in Portugal,17,27–29 but other international studies, such as the Slovenia SOBOTA-HF study.30 Additionally, the pilot study confirmed confirmed the assumptions regarding participants acceptance rates and the proportion of attendance at the mobile clinic and also contributed to enhance participants workflow, mobility within the mobile clinic and information provided to participants.

LimitationsThere are, however, some limitations and challenges that need to be recognized. The main challenge of the study, given that it is a population-based study, may lie in the potential impact of population non-adherence and non-compliance with the defined quotas in the sample design. This could significantly affect the representativeness of the sample and, consequently, the generalization of the study findings to the larger Portuguese population. Considering the sampling design with oversampling and the subsequent use of a weighting factor, we believe that we will manage to mitigate the hazards of not having a representative sample. Additionally, this study will not follow a random route sampling method, but a random sample of obtained adults residing in mainland Portugal and registered in primary care centers. The sampling method, whereby primary healthcare centers are selected to provide data, may also create a selection bias. Due to the mobile outpatient clinic constraints, institutionalized individuals, or subjects unable to visit the mobile outpatient clinic were also excluded. Additionally, given logistic constraints, this study will not be performed in the Autonomous Regions of Madeira and Azores. Nevertheless, these regions only account for 5% of the Portuguese population.

Our protocol uses natriuretic peptide measurement as a screening tool to find HF patients, following the ESC guidelines. In order to minimize the false-negative rate (younger age, obese, on diuretics, or HFpEF patients) we (i) maintained a low NT-proBNP cut-off of ≥125 pg/mL across all age spectrums, increasing sensitivity among older age ranges more prone to HFpEF, (ii) skipped NT-proBNP measurements for Stage 2 eligibility if the patient self-reported a prior history of HF and (iii) included a 5% random group of individuals that proceeded automatically to Step 2 in order to underwent a comprehensive echocardiography assessment independently of the NT-proBNP values. In contrast, to tackle the potential false-positives yielded by the chosen NT-proBNP cut-off, we plan conduct sensitivity analysis considering different age-specific cut-offs.31 We used self-reported symptoms (fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea and edema) but no signs of clinical congestion were documented, due to the design features of the study. However, and following the 2021 Universal Definition of Heart Failure, elevated NT-proBNP can be used as an objective surrogate of congestion in this setting. Finally, patients scoring 2–4 points in the HFA-PEFF algorithm will not undergo invasive hemodynamic evaluation, which is the gold-standard exam for this indeterminate subset of participants. However, a diastolic stress test exercise echocardiography will be performed in Stage 3, which is a validated recommended test and feasible in our population study setting.

Despite these limitations, PORTHOS will provide new and unique evidence about HF prevalence in Portugal, enabling the medical community and society to have unprecedented data to characterize and inform decision-makers on the burden associated with this syndrome in Portugal.

ConclusionPORTHOS is a large population-based study that will address knowledge gaps on the epidemiology, characteristics, and burden of HF in mainland Portugal. This will be the first population-based study in Portugal to determine the prevalence of HF and the distribution of the different HF phenotypes using NT-proBNP and comprehensive echocardiography, according to the 2021 ESC HF guidelines. It will also lead to a biobank that, in the future, may possibly contribute to the identification of new biomarkers of early HF development. Thus, it is expected that the results of this study may be able to inform clinicians and healthcare decision makers on the current HF-landscape in Portugal, and, consequently, support health policies on the optimization of HF identification, prevention, and management.

Conflicts of interestThere are the following potential conflicts of interest to consider, although without influence to the content of the work: R.B. has received speaker or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL, Daiichi-Sankyo, Janssen, JABA Recordati, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier, and Tecnimede. A.M.R. has received speaker or consulting fees, or investigational grants from Abbvie, Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer and Roche. F.F. has received speaker or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer and Novartis. J.P. has received speaker or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, Servier Portugal and Vifor Pharma. S.G. has received speaker or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier and Vifor Pharma. A.A. has received speaker or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. B.M. has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Servier and Vifor Pharma. C.F. has received speaker or consultancy or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Servier and Vifor Pharma. C.A. has received speaker or consulting fees from Abbott, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Lilly & Boehringer Ingelheim Alliance, Novartis, Pfizer and Servier. D.B. has received speaker or advisory board fees from, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bial, Novartis, Pfizer and Vifor Pharma. J.F. has received speaker or consulting or advisory board fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis. M.P. has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Merk SA, Novartis and Servier. P.S. has received speaker or consulting fees, or investigational grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Medinfar, MSD and Tecnimede. P.M.S has received speaker or advisory board fees, or investigational grants from AstraZeneca, Bial, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly & Boehringer Ingelheim Alliance, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier and Vifor Pharma. R.F-C. has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bial, Novartis and Servier. C.G. has received speaker or advisory board fees. PORTHOS study is funded by AstraZeneca. F.B., H.M., M.A., and M.P. are collaborators of AstraZeneca Portugal. J.S.C, L.M., H.C., I.K., A.T.T., L.F.A, R.C., M.S., A.C.F., J.G-J., L.F.P., V.G., R.M. and V.B., have no conflicts of interest to declare.

PORTHOS study arises from a scientific partnership between the Portuguese Society of Cardiology, AstraZeneca and NOVA Medical School. The authors are especially grateful to all the institutional partners that collaborated at various levels: Associação de Apoio aos Doentes com Insuficiência Cardíaca (AADIC), GlobalSports, Maria Design, Missão Continente (Sonae), Unilabs and GE. For the collaboration in the pilot study, the authors are grateful to Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos (Dr. Nuno Moreno and Dr. Daniel Seabra) and to Câmara Municipal de Matosinhos. We are also grateful to Prof. Artur Paiva and Dr. João Mariano Pêgo from Centro Hospitalar and Universitário de Coimbra. To the members of the study management team for their valuable contribute: Dra. Adriana Salgueiro and Dr. Diogo Pedroso.