Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome characterized by the loss of functional reserve, associated with higher mortality and less functional survival in cardiac surgery patients. The Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) is a comprehensive tool devised for brief frailty detection. To the best of our knowledge, there are no culturally adapted and validated frailty screening tools that enable the identification of vulnerability domains suited for use in the preoperative setting in Portugal. This was the motivation for this study.

ObjectivesTo assess the validity and reproducibility of the Portuguese version of the EFS.

MethodsProspective observational study, in a sample of elective cardiac surgery patients. The Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) translation and backtranslation were performed. Demographic and clinical data were collected, and the translated EFS translated, Geriatric Depression Scale, and Mini Mental State Examination Portuguese versions, Katz and Clinical Frailty Scales were administered. To assess validity Mann–Whitney test, Spearman's correlation coefficient, marginal homogeneity test and Kappa coefficient were employed. Reproducibility was assessed estimating kappa coefficient for the frailty diagnosis and the 11 EFS items. Intra-class correlation coefficients and the corresponding 95% confidence interval were estimated using linear mixed effects model.

ResultsThe EFS Portuguese version revealed construct validity for frailty identification, as well as criterion validity for cognition and mood domains. Reproducibility was demonstrated, with k=0.62 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42–0.82) and intraclass correlation (ICC)=0.94 (95% CI 0.89–0.97) in inter-observer test and k=0.48 (95% CI 0.26–0.70) and ICC=0.85 (95% CI 0.72–0.92) in intra-observer test.

ConclusionsThe EFS Portuguese version is valid and reproducible for use, suiting pre-operative frailty screening in a cardiac surgery setting.

A fragilidade é uma síndrome multidimensional caracterizada pela perda de reserva funcional, associada a maior mortalidade e menor sobrevivência funcional após cirurgia cardíaca. A Escala de Fragilidade de Edmonton (EFS) é uma ferramenta abrangente de deteção de fragilidade. Não existe ainda em Portugal uma ferramenta de rastreio culturalmente adaptada e validada que permita a identificação de domínios específicos de vulnerabilidade para utilização no pré-operatório.

ObjetivosAvaliar a validade e reprodutibilidade da versão portuguesa da EFS.

MétodosEstudo prospetivo observacional, realizado numa amostra de doentes propostos para cirurgia cardíaca. A EFS foi traduzida e retrotraduzida. Colheram-se dados demográficos e clínicos, aplicaram-se as versões traduzidas da EFS, Escala de Depressão Geriátrica e MMSE, as escalas de Katz e Clinical Frailty Scale. Validade avaliada utilizando o teste de Mann-Whitney, o coeficiente de correlação de Spearman, o teste de homogeneidade marginal e o coeficiente Kappa. Reprodutibilidade avaliada pelo cálculo do coeficiente kappa para o diagnóstico de fragilidade e para os 11 itens da escala. Coeficientes de correlação intraclasse e correspondentes intervalos de confiança a 95% estimados usando um modelo linear de efeitos mistos.

ResultadosA versão portuguesa da EFS demonstrou validade de constructo, assim como validade de critério nos domínios de cognição e humor. É reprodutível, com k=0,62 (95% IC 0,42-0,82) e CCI=0,94 (95% IC 0,89-0,97) no teste interobservador e k=0,48 (95% IC 0,26-0,70) e CCI=0,85 (95% IC 0,72-0,92) no teste intraobservador.

ConclusõesA versão portuguesa da EFS é adequada para rastreio pré-operatório de fragilidade em cirurgia cardíaca.

Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome characterized by the loss of functional reserve. It increases a person's vulnerability to adverse events when exposed to even minor stress. There is increasing evidence that regardless of the tool used, frailty assessment before major surgery adds value to predict post-operative mortality, complications and length of stay.1–3

Specifically, in a cardiac surgery setting the changing demographics and surgical case mix over the last 20 years has had implications on conventional risk scores performance and calibration (observed–expected mortality ratio) over time.4 Different frailty screening tools have been used before cardiac surgery and showed to outperform the EuroSCORE and Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) scores in mortality prediction.5,6 It is currently accepted that frailty is associated with higher mortality in elderly people with cardiovascular disease and less functional survival in cardiac surgery patients.5–7 However, the value of systematic frailty screening before surgery is not limited to better prognostic performance, it has also implications for adequate planning of care and clinical governance, especially if the tool in use enables the identification of vulnerability domains amenable to preoperative intervention and optimization.7

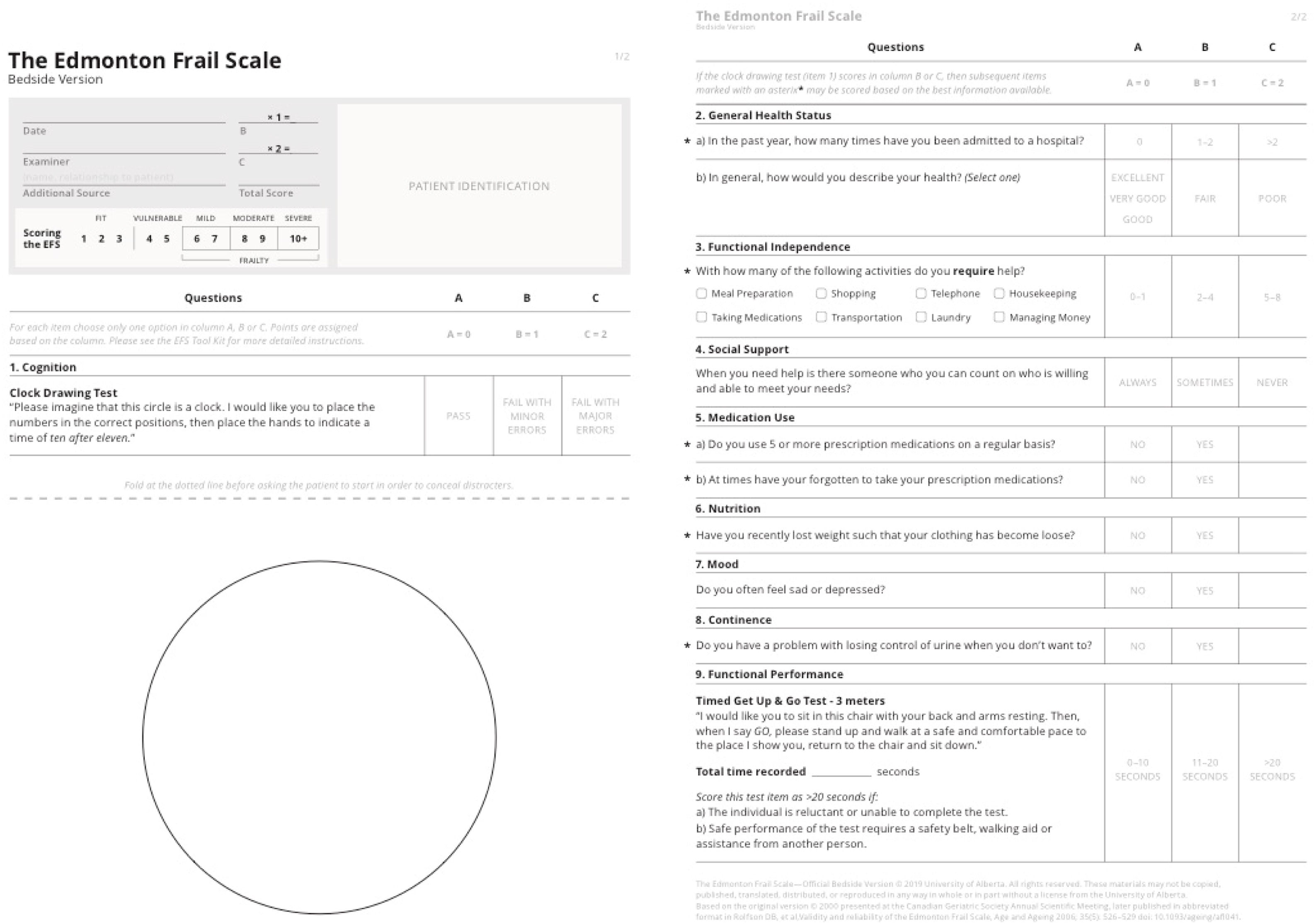

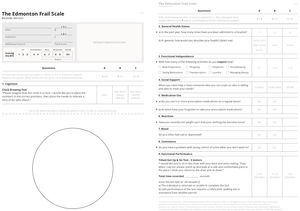

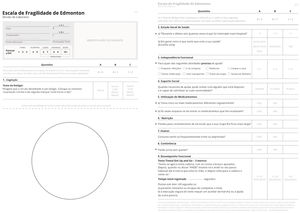

The most accepted diagnostic tool for frailty is the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) performed by gerontologists. However, it is time consuming and requires special training, which makes it difficult to apply in a preoperative setting. The Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) is a comprehensive tool (nine domains, eleven items) devised for brief frailty detection that can be applied in a busy preoperative setting. It allows frailty quantitative stratification and has been used for frailty screening and as a prognostic tool both in inpatient and outpatient settings.7–9

ObjectivesThis study aimed to assess the reproducibility and validity of the culturally adapted Portuguese version of the Edmonton Frail Scale in a population of elective cardiac surgery patients, in whom frailty is being studied as a potential prognostic factor.

The reproducibility of a tool is particularly important when there are many different tools in use, and no single gold standard, as is the case with frailty screening. It can be applied by different investigators to the same subject (inter-observer reproducibility) or by the same investigator to the same subject at two different times (intra-observer reproducibility).10

The validity of a tool refers to how well a measurement describes the phenomena of interest. Construct validity addresses how well a measuring tool agrees with a theoretical construct.10 Frailty is conceptualized as multidimensional loss of reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors. As a multidomain tool, the Edmonton Frail Scale, captures frailty multidimensional nature, distinguishing it from disability, cognitive deficit or aging alone. Criterion validity represents the degree to which a measure correlates with accepted existing measures.10 To assess criterion validity for P-EFS, Clinical Frailty Scale, another frailty screening tool, was used.

Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, there are no adapted and validated frailty screening tools currently used in the preoperative setting in Portugal, which led us to perform this study.

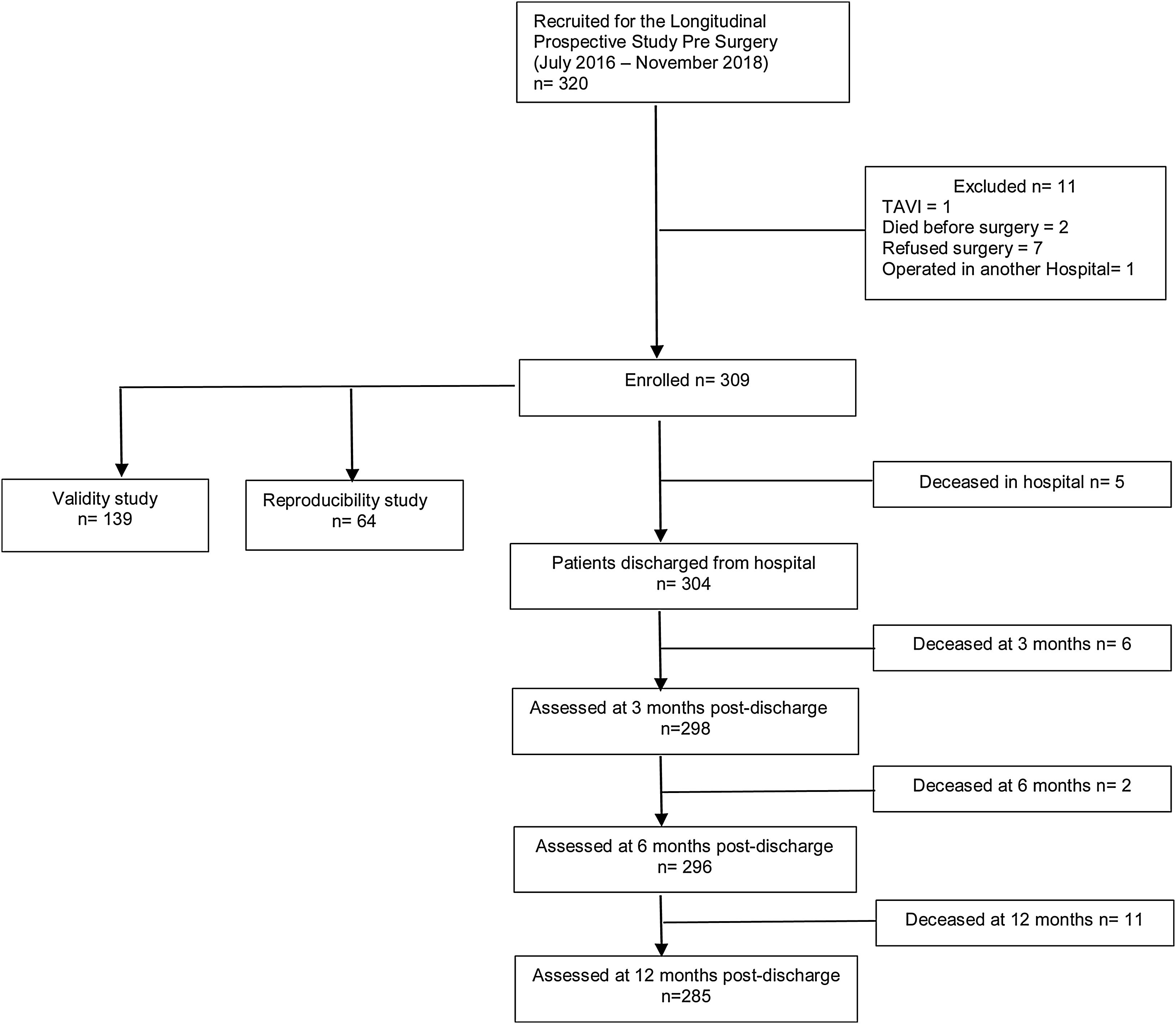

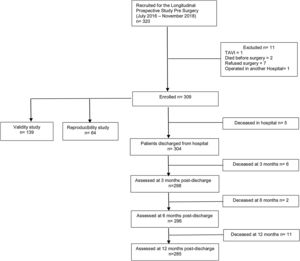

MethodsStudy design and subjectsThis study was approved by the NOVA Medical School/Faculdade de Ciências Médicas and Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central (CHULC) prior to initiation. We conducted a prospective observational study of consecutive elective cardiac surgery patients between July 2016 and November 2018, who were followed up for one year, and will be the subject of a different manuscript. To calculate the larger study sample size, an α=0.05, an error of 0.04 and a frailty prevalence of 15% were considered, achieving a sample size of 306 patients.11,12 At our institution, all elective cardiac surgery patients are observed in preoperative anesthesia consultations. Patient recruitment took place once the nature and goals of the study had been explained and consent for data collection obtained. A convenience sample of consecutive patients 65 years old and above, admitted for elective valve or myocardial revascularization surgery and observed by the principal investigator in preoperative anesthesia consultation, was selected. For the purpose of validity and reproducibility studies, we estimated subsamples of 139 and 64 patients, respectively (detailed ahead). Exclusion criteria were complex aortic arch procedures, urgent or redo surgery, and the presence of sensory or cognitive deprivation that prevented communication between patients and investigators. Figure 1 depicts the flowchart from enrolled patients for the prospective longitudinal, validity and reproducibility studies.

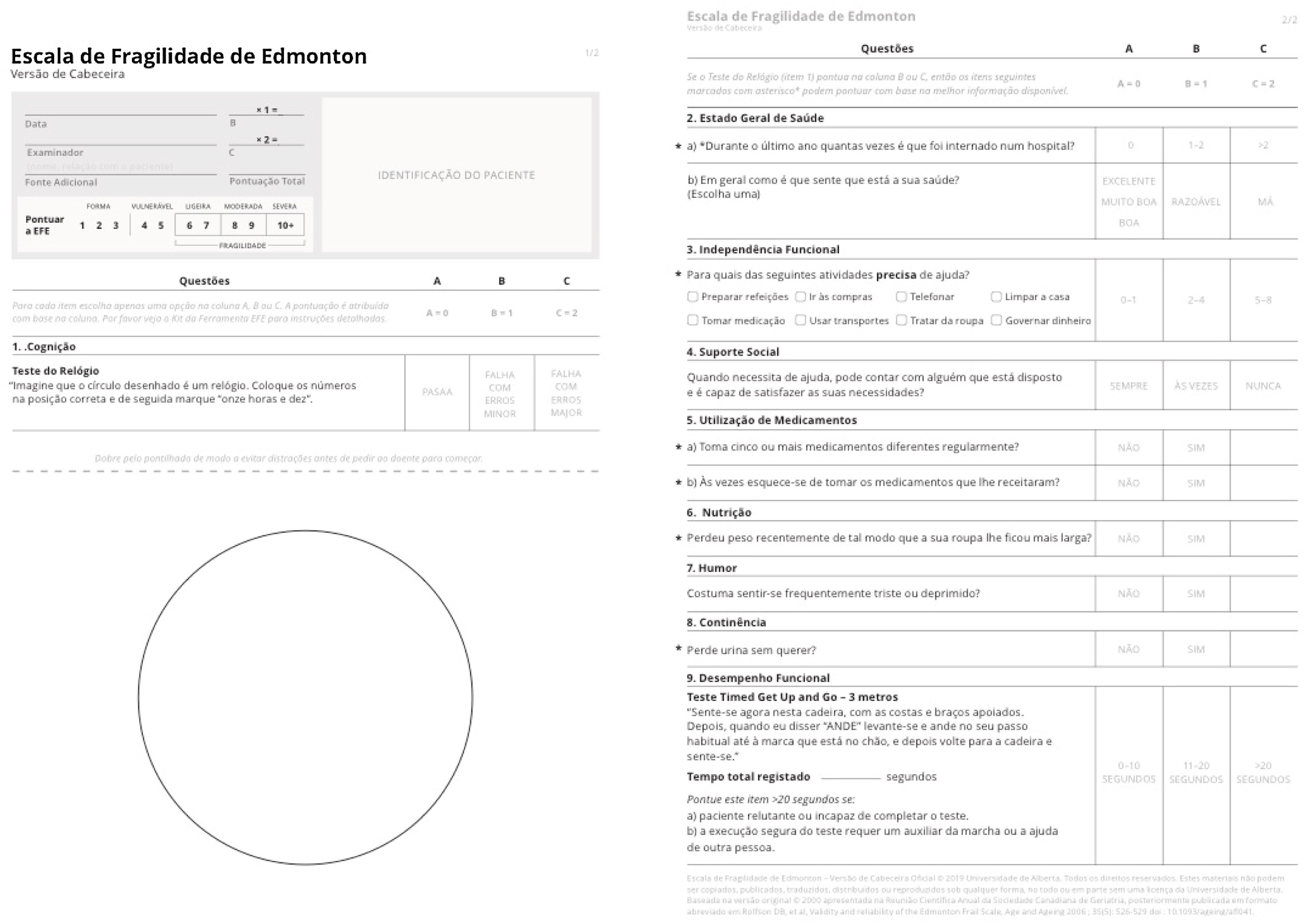

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation methodsPrior to reproducibility testing and after obtaining permission from the EFS authors, the original English version of the EFS was translated to Portuguese by two independent translators. A group of eight doctors from different specialties (anesthesiologists, cardiac surgeons, and family physicians) with knowledge of the frailty construct met in a focus group to build a final consensus Portuguese version. Both the final Portuguese version and its English backtranslation were sent to the original authors for approval. The original English and Portuguese versions, licensed by the University of Alberta for use in this study, are depicted in Figures 2 and 3.

Prior to the start of the study, the principal investigator administered the Portuguese EFS adapted version to ten eligible patients to identify possible difficulties with its use and contacted the original authors to clarify any doubts that arose. Subsequently, another two collaborators were trained by the principal investigator to administer the scale.

Reproducibility and validity studyThe maximum scoring for EFS is 17 and cut-points proposed in the official 2019 EFS webpage were considered in frailty diagnosis (1–3 fit; 4–5 vulnerable; 6–7 mild frailty; 8–9 moderate frailty; 10 or more severe frailty).

Other pre-defined variables were collected as part of the larger study, including demographic and clinical variables, such as number of school years, marital status, main surgical diagnosis, and scores in the Portuguese adapted versions of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)13,14 and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),15 as well as Katz16 scale and Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)17 scores. In addition, the prognostic scores EuroSCORE II18 (European System for Cardiac Operation Risk Evaluation) and STS19,20 were collected.

To test for reproducibility of the P-EFS adapted version and assuming that good agreement would be a Kappa coefficient >0.60 or an intraclass correlation coefficient >0.8,21 an α=0.05 and a β=0.10 (power of 0.90), we estimated a sample size of 30 subjects. To avoid exposure to the P-EFS related bias, we more than doubled the sample size and performed 34 inter-observer and 33 intra-observer agreement tests in 64 patients. P-EFS was re-applied within a minimum interval of 2h and a maximum of 2 months. A substantial part of the enrolled patients lived more than 50km away from the hospital and/or were not totally autonomous in traveling to the hospital. Therefore, the research team agreed to administer P-EFS at patients’ scheduled appointments for routine and essential examinations for preoperative assessment, and no patient returned exclusively for the purpose of P-EFS re-administration.

To test for construct and criterion validity, 139 patients provided at least 0.80 power (effect size=0.4 and α=0.05, two-sided test) to detect differences among groups.

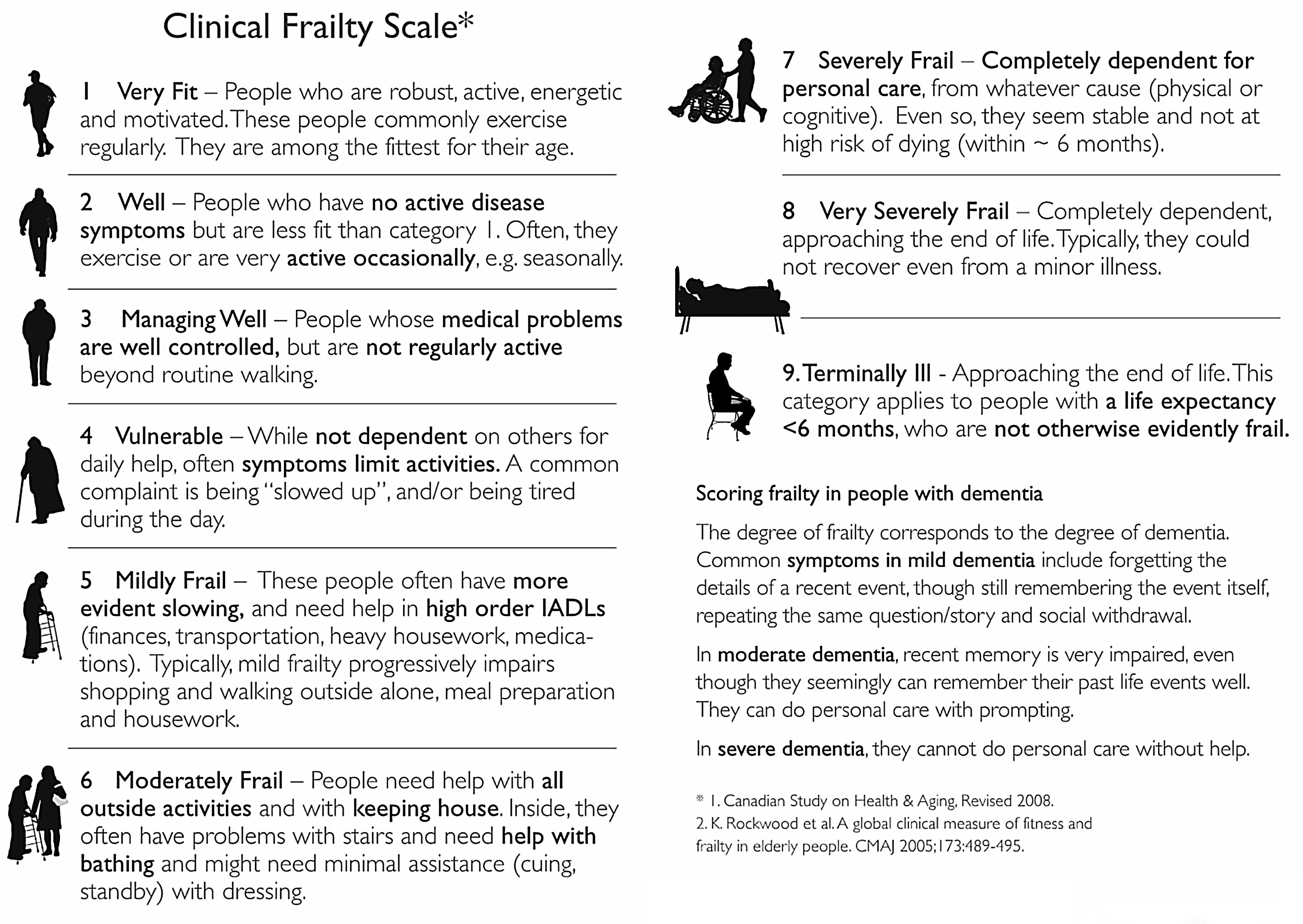

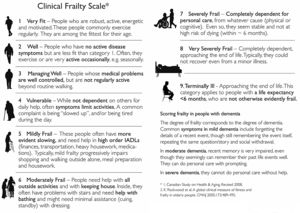

To assess construct validity, we evaluated the agreement of Katz and MMSE measurements with P-EFS total scores, and regarding criterion validity we compared P-EFS and Clinical Frailty Scales scores. The Clinical Frailty Scale has been widely used both in outpatient and acute care settings. It is an ordinal scale that incorporates clinician judgment and employs a 1–9 scoring system that includes the evaluation of many frailty domains. It stratifies frailty into fit (1–3), vulnerable (4), frail (5–8) and terminally ill (9) (Figure 4). For P-EFS specific domains of cognition and mood, we assessed criterion validity by comparing the Clock Drawing Test with MMSE and Mood questions in P-EFS with GDS30 and GDS 15.

Regarding MMSE normative data, we used both Morgado et al.’s13 cut-off points for cognitive deficit, as they are the most widely accepted by the Portuguese medical community, and the more recent Freitas et al.14 normative data.

Content validity assessment was not performed as it would require the CGA of study participants to establish a frailty diagnosis, and this is not part of a standard preoperative evaluation in clinical practice. On the other hand, the content validity for the EFS was established by the authors of the original version when it was first described.

Statistical analysisThe characteristics of study participants were described with frequencies (percentages) and with median and range (min–max), as appropriate. The Mann–Whitney test, Spearman's correlation coefficient, marginal homogeneity test, and Kappa coefficient were used as needed to assess validity.

For reproducibility assessment, the Kappa coefficient was estimated for both frailty diagnosis and the 11 EFS items in inter- and intra-observer analyses. To assess the intra-observer repeatability and inter-observer reproducibility, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were estimated using linear mixed-effects models.

The level of significance was set at α=0.05. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 25.0; IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

ResultsValidity studyIn the 139 patients sample used for validity study, mean age was 73.55 years (5.84), with 57.6% male and 18.0% widowers, and a mean years of schooling of 5.49 (4.23). In the surgery group, 47.5% underwent aortic valve replacement, 30.2% to coronary artery bypass graft, 2.2% to mitral valve replacement, and the remaining patients underwent more than one surgery (Table 1). The median raw EFS score was 6, ranging from 1 to 13. Considering the EFS score in categories, 15 (10.8%) were fit (1–3), 35 (25.2%) were vulnerable (4–5), 49 (35.3%) exhibited mild frailty (6–7), 25 (18%) exhibited moderate frailty (8–9), and 15 (10.8%) had severe frailty (≥10).

Demographic and clinical data in the validity study sample.

| Validity study sample (n=139) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 73.55 (5.84) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 57.6% |

| Female | 42.4% |

| Schooling years | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.49 (4.23) |

| Median (min–max) | 4 (0–22) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 76.3% |

| Widowed | 18.0% |

| Other | 5.8% |

| Surgery type | |

| CABG | 30.2% |

| Valve surgery | 56.2% |

| CABG+Valve | 13.6% |

Abbreviations: CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; SD: standard deviation.

The EuroSCORE II, STS Mortality, and STS Morbi-mortality, GDS30 and GDS15, MMSE, Katz, and CFS descriptive data are presented in Table 2.

Description of different scores used in validity study.

| Score | n=139 |

|---|---|

| EuroSCORE II; median (min–max) | 1.62 (0.64–6.48) |

| STS Mortality; median (min–max) | 1.52 (0.00–11.36) |

| STS Morbimortality; median (min–max) | 11.15 (3.33–40.82) |

| GDS30 (0–30); median (min–max) | 8 (0–28) |

| GDS15 (0–15); median (min–max) | 3 (0–13) |

| MMSE [0–30); median (min–max) | 28 (14–30) |

| Katz; n (%) | |

| 1 to 5 – dependent for at least one BADL | 49 (35.3) |

| 6 – independent for all BADL | 90 (64.7) |

| Clinical Frailty Scale; n (%) | |

| 3 – Managing well | 6 (4.3) |

| 4 – Vulnerable | 68 (48.9) |

| 5 – Mildly Frail | 53 (38.1) |

| 6 – Moderately Frail | 11 (7.9) |

| 7 – Severely Frail | 1 (0.7) |

Abbreviations: BADL: Basic Activities of Daily Living; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Cardiac Surgery Risk; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

Analysis of GDS30 results revealed that 63.3% of the patients had no depressive symptoms, 31.7% had mild depression, and 5% had severe depression. When GDS15 was considered, 33.1% had depressive symptoms. Regarding P-EFS mood questions, 40.3% answered “yes” when asked about sadness or depression.

Regarding criteria validity for the mood domain, the mood question in P-EFS showed good agreement (k=0.651, p<0.001) with P-GDS30 and moderate agreement with P-GDS15 (k=0.569, p<0.001).

For the screening of cognitive deficits using MMSE, we considered both the 2009 and 2014 normative data for the Portuguese population. According to the 2009 criteria, only 12.2% of patients scored for cognitive deficit, but this percentage increased to 19.4% when the 2014 criteria were applied. In the validity sample and analysis of the P-EFS cognition domain, 26.6% scored for major errors in the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), and the remaining had either no errors (29.5%) or minor errors (43.9%).

Regarding criterion validity testing for the cognition domain, two categories in the CDT were considered: one composed of “no errors + minor errors” and the other “major errors”, as only these are valued as cognitive deficit in the CDT. Clock Drawing Test in the P-EFS showed fair to moderate agreement with P-MMSE either considering 2014 criteria (k=0.356, p<0.001) or 2009 criteria (k=0.422, p<0.001).

Regarding criterion validity, only a fair agreement between P-EFS and CFS scores was found (k=0.224, p<0.001) and as such we could not demonstrate criterion validity for P-EFS using CFS as another accepted measure of frailty.

To test for construct validity, the P-EFS total score was compared with the Katz and MMSE scores. P-EFS total scores were significantly different between patients with a Katz score of 6 (independent on all BADL) and Katz scores <6 (dependent on at least one BADL) (p<0.001).

The P-EFS total score was negatively correlated with the MMSE total score (Spearman rho=−0.357, p<0.001) with increasing P-EFS scores associated with decreasing MMSE scores. When the 2014 and 2009 criteria for cognitive deficit were considered, a statistically significant association existed between the P-EFS total score and MMSE screening cognitive deficit (p=0.002 and p=0.001, respectively).

Reproducibility studyIn the reproducibility study, the mean age was 74.85 (SD=6.32) years and 74.91 (SD=6.50) years in the inter-observer and intra-observer study sample, respectively, with 52.9% (inter-observer) and 48.5% (intra-observer) male, 26.5% (inter-observer) and 21.2% (intra-observer) widowers, and 84.8% (inter-observer) and 57.6% (intra-observer) with no schooling or less than 4 schooling years, respectively (Table 3).

Clinical and demographic data in the reproducibility study sample.

| Inter-observer (n=34) | Intra-observer (n=33) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 74.85 (6.32) | 74.91 (6.50) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 52.9% | 48.5% |

| Female | 47.1% | 51.5% |

| Schooling years | ||

| 0–3 schooling years | 84.8% | 57.6% |

| >3 schooling years | 15.2% | 42.4% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 58.8% | 69.7% |

| Widowed | 26.5% | 21.2% |

| Other | 14.7% | 9.1% |

| Surgery type | ||

| CABG | 35.3% | 24.2% |

| Valve | 58.8% | 57.6% |

| CABG+Valve | 5.9% | 18.2% |

Abbreviations: CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; SD: standard deviation.

Frailty raw scores and classified into five categories of descriptive results for the inter- and intra-observer study samples are shown in Table 4. The two measurements were obtained by two different investigator in the inter-observer study and by the same investigator at two distinct time points in the intra-observer study.

P-EFS Raw Scores and classified into categories for inter- and intra-observer sample studies.

| P-EFS Raw Scores and with categories | Inter-observer (n=34) | Intra-observer (n=33) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-EFS1 | P-EFS2 | P-EFS1 | P-EFS2 | |

| Raw Score; median (min–max) | 6 (2–11) | 6 (2–11) | 7 (0–11) | 7 (2–13) |

| P-EFS Score categories; n (%) | ||||

| Fit (1–3) | 3 (8.8) | 4 (11.8) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (15.2) |

| Vulnerable (4–5) | 11 (32.4) | 11 (32.4) | 6 (18.2) | 5 (15.2) |

| Mild frailty (6–7) | 10 (29.4) | 7 (20.6) | 12 (36.4) | 13 (39.4) |

| Moderate frailty (8–9) | 5 (14.7) | 7 (20.6) | 8 (24.2) | 6 (18.2) |

| Severe frailty (≥10) | 5 (14.7) | 5 (14.7) | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) |

Abbreviations: P-EFS: Portuguese Edmonton Frail Scale; EFS1 and EFS2 stand for measurements 1 and 2.

Regarding re-application of the scale, for the inter-observer test, median was 0 (P25=0; P75=1) days and mean was 3.32 (SD=10.57) days. For the intra-observer test, median was 21 (P25=7; P75=36) days and mean was 30.51 (SD=52.26).

Intraclass correlation coefficient estimates obtained with the inter- and intra-observer study samples were 0.94 (95% CI 0.89–0.97) and 0.85 (95% CI 0.72–0.92), respectively.

The kappa coefficient estimates and percentage of agreement regarding the 11 items of P-EFS and the different P-EFS categories are depicted in Table 5.

Kappa coefficient estimates and agreement in inter- and intra-observer study.

| P- EFS item | Inter-observerKappa | Agreement | Intra-observerKappa | Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clock Drawing Test | k=0.73(95% CI 0.53–0.92) | 82.4% | k=0.77(95% CI 0.58–0.95) | 84.8% |

| In the past year, how many times have you been admitted to a hospital? | k=1.00(95% CI 1.00–1.00) | 100% | k=0.89(95% CI 0.68–1.10) | 97.0% |

| In general, how would you describe your health? | k=0.69(95% CI 0.46–0.91) | 82.4% | k=0.20(95% CI −0.09–0.48) | 54.5% |

| With how many of the following activities do you require help? | k=0.67(95% CI 0.44–0.89) | 79.4% | k=0.89(95% CI 0.75–1.04) | 93.9% |

| When you need help is there someone who you can count on who is willing and able to meet your needs? | k=0.90(95% CI 0.69–1.10) | 97.1% | k=0.63(95% CI 0.16–1.10) | 93.9% |

| Do you use 5 or more prescription medications on a regular basis? | k=0.80(95% CI 0.52–1.06) | 94.1% | k=0.87(95% CI 0.63–1.12) | 97.0% |

| At times, have you forgotten to take your prescription medications? | k=0.61(95% CI 0.35–0.87) | 82.4% | k=0.54(95% CI 0.22–0.87) | 81.8% |

| Have you recently lost weight such that your clothing has become loose? | k=0.86(95% CI 0.67–1.05) | 94.1% | k=0.87(95% CI 0.70–1.04) | 93.9% |

| Do you often feel sad or depressed? | k=0.82(95% CI 0.62–1.01) | 91.2% | k=0.82(95% CI 0.62–1.01) | 90.9% |

| Do you have a problem with losing control of urine when you don’t want to? | k=0.92(95% CI 0.77–1.07) | 97.1% | k=0.91(95% CI 0.75–1.08) | 97% |

| Timed get up and go test (TUG Test) – 3 meters | k=0.60(95% CI 0.35–0.85) | 79.4% | k=0.73(95% CI 0.51–0.95) | 84.8% |

| EFS categories | k=0.62(95% CI 0.42–0.82) | 70.6% | k=0.48(95% CI 0.26–0.70) | 60.6% |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; k: Kappa coefficient; P-EFS: Portuguese Edmonton Frail Scale; TUG: timed up and go test.

The Portuguese EFS version was shown to have construct validity for the frailty construct.

The construct validity analysis showed a negative correlation between P-EFS and MMSE, as expected, since the two measures were inversely related. There was a significant difference in P-EFS scores between patients, with those with cognitive deficits displaying the highest P-EFS scores, considering either 2009 or 2014 normative data for MMSE. P-EFS scores were statistically different between patients totally independent of BADL compared to those dependent on at least one BADL on the Katz scale.

Regarding criterion validity, it showed only fair agreement with CFS scores. CFS is an ordinal scale, relying on clinician judgment and is more subjective in nature than EFS, which is a quantitative scale, measuring objectively different function domains. Studies in which both scales were used to assess frailty in the same population found slightly different values for frailty prevalence.22 Although both scales have demonstrated construct validity for frailty in different settings, their essentially different nature may explain our findings showing only fair agreement between them.

For the specific domain cognition, there was moderate agreement between the Clock Drawing Test considering two categories (major errors vs. no errors+minor errors) and the presence of cognitive deficits in MMSE, according to both 2014 and 2009 normative data. For the specific domain Mood, there was good agreement between the mood question in P-EFS and either the GDS30 or GDS15 in identifying patients with depressive symptoms.

P-EFS showed to be reproducible for the studied population, with moderate to good agreement when considering intra- and inter-observer studies, respectively.

There were some differences in agreement for inter- and intra-observer analyses. Higher agreement, both in inter- and intra-observer studies, was observed in the items of the scale that rely more on objective information or patient performance, such as the clock drawing and TUG tests, the number of admissions in hospital, the number of prescribed medications, and the questions about nutrition, continence, and mood. The lowest agreement was observed for the item “In general, how would you describe your health?” in the intra-observer study. In addition, the item “At times, do you forget to take your prescription medications?” showed moderate agreement in both the inter-and intra-observer tests. One possible explanation for the lower agreement observed is the more subjective nature of these questions.

Regarding the diagnostic categories for frailty, we observed that for the extremes of the scale, there was a coincidence between the two measurements in the frailty category. For the intermediate categories (vulnerable, mild, and moderate frailty), some patients changed category between the two measurements, with a larger proportion scoring for mild, moderate, or severe frailty in the second measurement. A possible contributing factor to this change was the interval between P-EFS re-administration. Considering the dynamic nature of frailty as a condition, it is possible that a second measurement one to two months after the first measurement captured a slightly different health condition. The research team decided to perform repeated measures on patients’ already scheduled visits to the hospital as a strategy to maximize adherence by prioritizing the patients’ convenience, given their age and functional independence. Although it has optimized adherence, it may have been associated with changes in the patients’ frailty, reflected in agreement.

One aspect to mention is the ease of administration of this scale. The three elements involved in EFS administration were physicians (two anesthesiologists and a graduate medical student), with interest in geriatric medicine, who did not have any previous intensive or very specific training in this field.

ConclusionsAs intended by the original authors for EFS, the Portuguese adapted version was shown to be reproducible and valid for use, suiting the purpose of frailty screening in a few minutes by health professionals other than gerontologists. It enables the identification of frail patients, stratification of patients according to frailty from mild to severe, and also to identify specific domains of vulnerability, which can be addressed and optimized prior to surgery in order to benefit the patient and improve prognosis. It also provides the health team, the patient, and its family with additional information that can be used while considering surgery and global health status in a specific patient, and therefore, make better informed decisions that represent value to the patient, to the health team, and to the system.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To Dr. Darryl Rolfson for his assistance throughout this work.

To Dr. Isabel Fragata, former Anesthesiology Head of Department at Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Central, for her encouragement and support.

To all the members of the panel for EFS Portuguese translation final version: Professor José Fragata, Professor Maria-Amália Botelho, Professor Pedro Pires Coelho, Dr. Isabel Fragata, Dr. Helena Barrios, Dr. Ângela Sá, Dr. Miguel Ferreira and Dr. César Magro.

To Sandra André, from the Administrative Bureau in Cardiothoracic University Clinic at Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Central.