Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is a rare facial pain syndrome, which in more rare cases can be associated with syncope. We present the outcome of a case report that combines this rare association that received medical therapy with anti-epileptic medication and permanent dual chamber pacemaker implantation.

In this case, syncope episodes were associated with both vasodepressor and cardioinhibitory reflex syncope types. The patient found relief from syncope, hypotension, and pain after initiation of anti-epileptic therapy. Although a dual chamber pacemaker was implanted, the pacemaker interrogation revealed no requirement for pacing at one-year follow-up.

As far as we know, this is the first case that reports pacemaker interrogation during follow-up and, taking into account the absence of pacemaker activation at one-year follow-up, the device was not needed to prevent bradycardia and syncope episodes.

This case report supports the current guidelines for pacing in neurocardiogenic syncope, by demonstrating a lack of requirement for pacing in the event of both cardioinhibitory and vasodepressor responses.

A nevralgia do glossofaríngeo é uma síndrome rara, causadora de dor facial que, mais raramente, pode estar associada a síncope.

Apresentamos o resultado de um caso clínico que combina esta rara associação, cujo tratamento incidiu na terapêutica médica com a instituição de fármacos antiepiléticos e na implantação de um pacemaker definitivo de dupla câmara.

Neste caso clínico, os episódios sincopais encontravam-se relacionados com ambos os componentes vasodepressor e cardioinibitório da síncope reflexa, tendo a paciente apresentado cessação dos episódios álgicos, sincopais e de hipotensão arterial após a instituição de terapêutica farmacológica antiepilética com carbamazepina. Embora se tenha procedido à implantação de um pacemaker definitivo de dupla câmara, a interrogação do dispositivo após um ano de seguimento revelou a ausência de ativação significativa do mesmo.

Este é o primeiro caso que reporta os resultados da interrogação de um pacemaker durante o seguimento de um paciente com nevralgia do glossofaríngeo com síncope reflexa. Tendo em conta a ausência de ativação do pacemaker definitivo de dupla câmara após um ano de seguimento, este dispositivo não foi necessário para evitar os episódios de bradicardia e síncope.

Este caso clínico suporta as diretrizes atuais para a implantação de pacemaker definitivo nos casos de síncope neurocardiogénica ao evidenciar a ausência de ativação do pacemaker permanente num caso de síncope neurocardiogénica, onde ambos os componentes cardioinibitório e vasodepressor se encontravam presentes.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia (GN) is a rare facial pain syndrome, with an incidence of only 0.2–1.3% of the facial pain syndromes.1 More rarely, it can be associated with syncope.2

We present the outcome of a case that combines this rare association that received medical therapy with anti-epileptic medication and permanent dual chamber pacemaker implantation.

Case reportAn 80-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a two-day history of syncope, preceded by intermittent sharp and severe pain in the right pharynx, lasting five to 25 s, which then radiated to the ipsilateral pathway.

Pain had started two months previously, with progressive intensity and frequency in the two weeks prior to admission, amounting to >100 episodes per day, without circadian rhythm variability. They were, however, so intense that they woke the patient up while sleeping. The pain was trigged by swallowing, chewing, and talking.

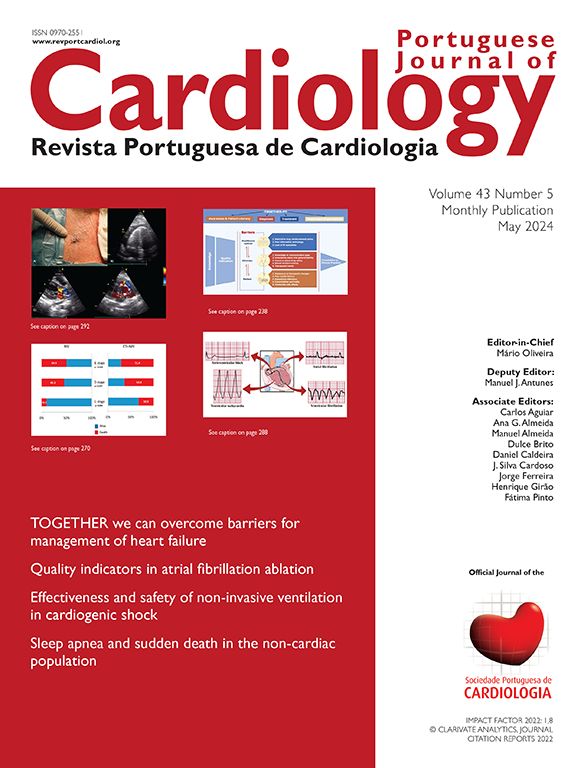

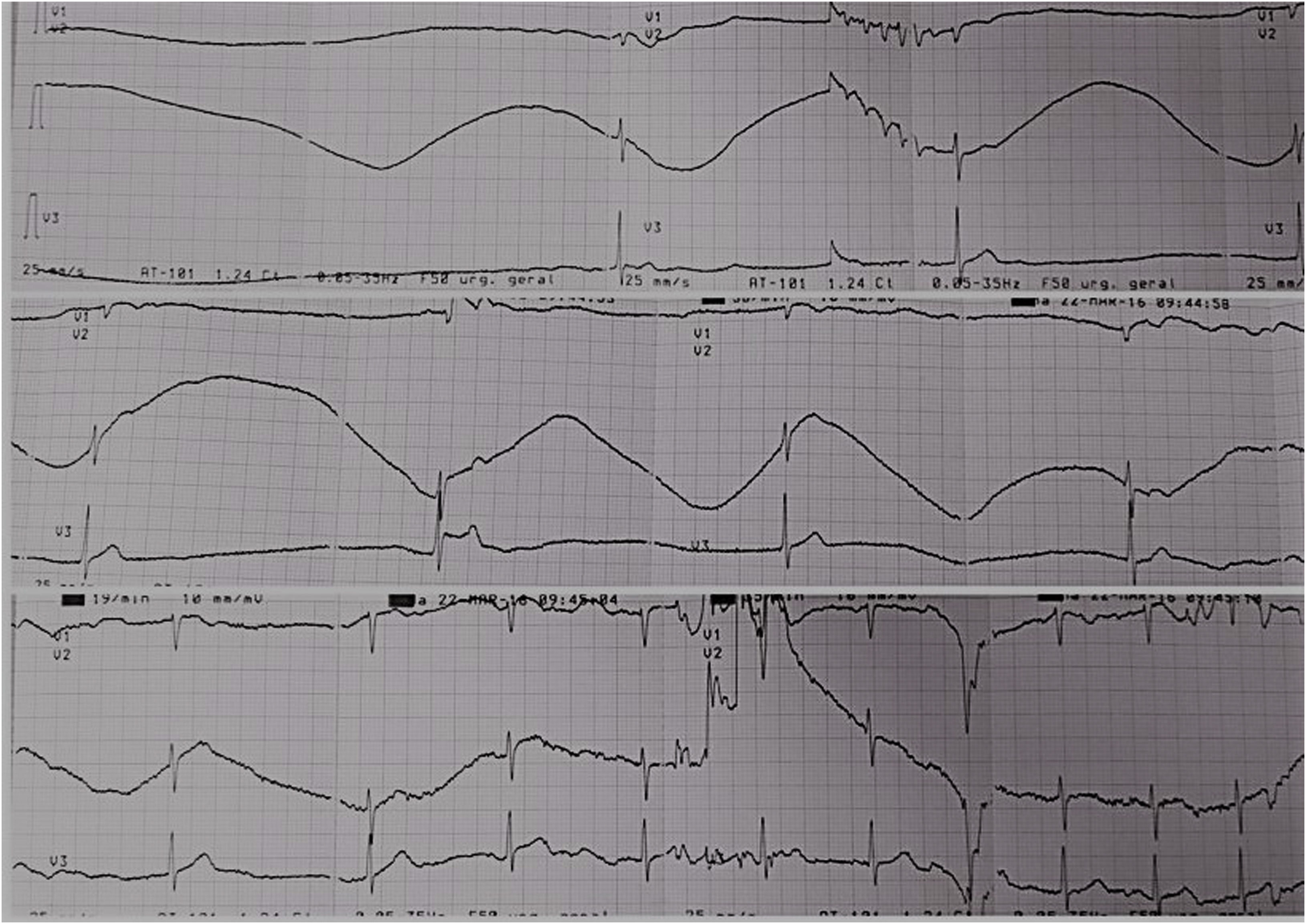

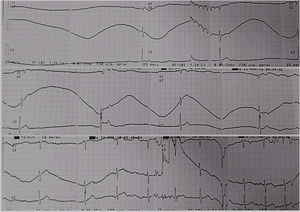

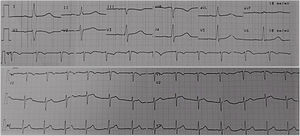

At the emergency department, she had syncope episodes associated with an asystole period lasting more than six seconds with low escape beats (Figure 1), and hypotension. Between these episodes, she was in sinus rhythm with no abnormalities in electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 2). Her medication history was unremarkable for negative chronotropic drugs. Due to severe sinus bradycardia and asystole during the pain episodes, a temporary transvenous pacemaker was placed to prevent syncope.

During the first days of her hospital stay, the patient had recurrence of cervical pain and, in the course of the pain episodes, she had transient symptomatic hypotension with bouts of systolic drops pressure over 40 mmHg, but no more syncope episodes were observed.

Both physical and neurological examination, blood tests and echocardiography were normal. Cranial computer tomography (CT) scan and cervical angio-CT did not reveal any signs of glossopharyngeal nerve impingement.

In the absence of syncope recurrence with a temporary pacemaker (and despite the vasodepressor component) with pain paroxysms, the decision was taken to implant a permanent dual chamber pacemaker.

After glossopharyngeal neuralgia associated with syncope was diagnosed, the patient started on 200 mg carbamazepine, twice daily, with clinical improvement.

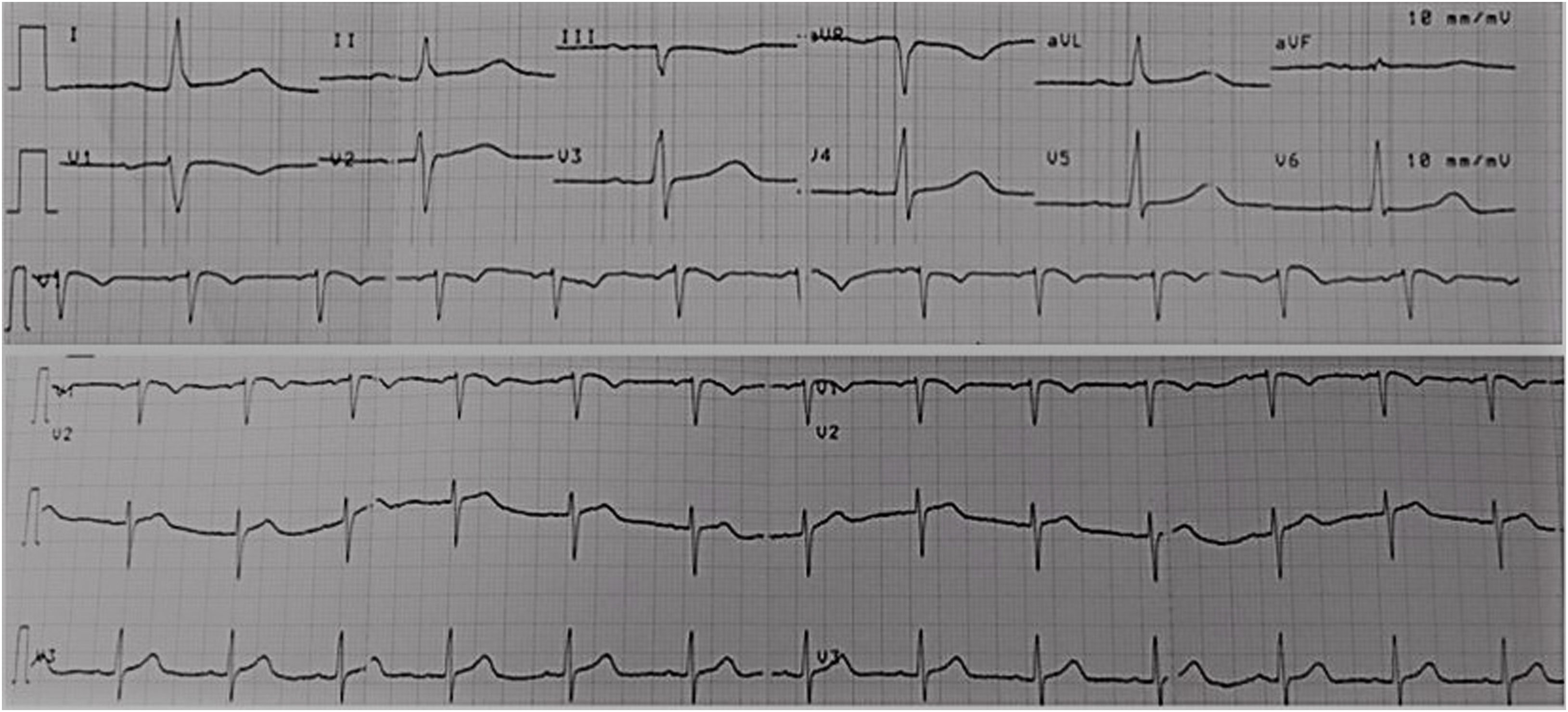

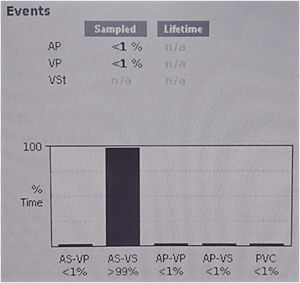

The dose was up-titrated to 600 mg daily and she was asymptomatic at discharge. At one-year follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, without pain episodes or syncope. Pacemaker interrogation revealed pacing rates <1% (Figure 3).

DiscussionWe present a case that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of classic GN3 and was treated with both anti-epileptic medication (carbamazepine) and permanent dual chamber pacemaker implantation.

Glossopharyngeal syncope is described as a severe transient stabbing pain, experienced in the ear, base of the tongue, tonsillar fossa or beneath the angle of the jaw.3 It is commonly provoked by swallowing, talking or coughing and in most of cases it occurs in the left side and in patients >50 years old.3,2

The majority of GN are idiopathic, and a comprehensive head and neck clinical examination as well as radiological examinations (including CT and Magnetic Resonance Imaging scans) usually do not reveal any abnormalities.3

Although most of the GN cases are idiopathic, some of them might be secondary to other causes such as compression of the glossopharyngeal nerve by vascular structures, tumors, calcified stylohyoid ligament, elongated styloid process (Eagle syndrome), occipital cervical malformations, inflammatory processes, intracranial vascular compression, direct carotid puncture, trauma, dental extractions, multiple sclerosis and Paget's disease.4,5

Syncope episodes present with bradycardia or asystole, hypotension and ECG changes that include various arrhythmias.4 The mechanism by which GN leads to syncope is not yet fully understood.6 Most proposed mechanisms are based on the close anatomical relationship between the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves in the medulla oblongata and the possibility of the formation of a vagoglossopharyngeal reflex arc.7 The reflex arrhythmia could be explained by the fact that the afferent nerve impulses traveling within the glossopharyngeal nerve may reach the nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the midbrain and, via collateral fibers, reach the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve.7 Additionally, the fibers of the carotid sinus nerve, also known as Hering's nerve, join the glossopharyngeal nerve and terminate in the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve, providing a route by which glossopharyngeal afferent impulses may produce vagal nerve stimulation.8 Individual differences in the susceptibility of the dorsal motor nucleus to the pain impulse may explain why not all cases are associated with syncope.9

The treatment for GN can be pharmacological, which is the first line of treatment, or surgical, which is recommended in secondary GN due to the relatively low efficacy of drugs in these cases, and should also be considered in situations of drug intolerance, inefficacy, allergies or side effects associated with medical therapy.4,5 Anti-epileptic drugs are used to control symptoms of idiopathic GN, with carbamazepine being the main representative drug.2

The management of GN-related syncope depends on whether there is a vasodepressor or cardioinhibitory response, or both, and which is predominant.10

The requirement of a pacemaker for patients presenting with a neuro-cardiogenic syncope has been controversial and now it is not recommended by routine, especially when a vasodepressor mechanism is involved.8,11,12 Pacemaker implantation does not relieve the patient from pain symptoms and is unlikely to be effective in preventing syncope in patients with an important vasodepressor response, in which avoidance behavior is effective and preferred.4,11,12

However, in a select population of patients >40 years of age with recurrent unexpected syncope and documented spontaneous pauses >3 seconds correlated with syncope or an asymptomatic pause >6 seconds, dual chamber pacing reduced syncope recurrence.12 The benefit does not seem to extend to patients with a positive tilt-table test that induced a vasodepressor response.12

In this case report, syncope was related to both vasodepressor and cardioinhibitory reflex syncope types. The patient had relief of syncope, hypotension and pain episodes once anti-epileptic therapy carbamazepine was started. Although a dual chamber pacemaker was implanted, the pacemaker interrogation revealed no requirement for pacing at one-year follow-up.

There are few cases reported in the literature of patients diagnosed with GN with syncope treated with pacemaker implantation and pharmacological therapy. The importance of implanting a pacemaker to avoid syncope in follow-up of these patients remains uncertain.

As far as we know, this is the first case that reports pacemaker interrogation during follow-up and, taking account the absence of pacemaker activation at one-year follow-up, the device was not necessary to prevent bradycardia and syncope episodes.

This case report supports the current guidelines for pacing in neuro-cardiogenic syncope, the current prevailing expert opinion and the results of the randomized trial VPS-II, by demonstrating a lack of requirement for pacing in a case of neuro-cardiogenic syncope with both cardioinhibitory and vasodepressor responses.12–14

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.