Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. The administration of low doses of aspirin in secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has been clearly established. However, the most recent guidelines do not recommend aspirin in primary prevention, reserving it for high-risk patients and after a risk/benefit assessment. The aim of this study was to assess adherence to European guidelines for the use of aspirin in primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD in primary health care.

MethodsThe study population consisted of individuals aged >50 years registered at two primary health care units without (primary prevention) and with previous ASCVD events (secondary prevention).

ResultsWe studied a total of 1262 individuals, 720 in primary prevention and 542 in secondary prevention. A total of 61 individuals (8.5%) were under aspirin therapy in primary prevention, most of them taking 150 mg/day (57%). In secondary prevention, 195 patients (27%) were receiving aspirin only, most taking 150 mg/day (52%), and 166 patients (31%) were not under any antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy. The 100 mg dosage was predominant in patients with ischemic heart disease with (64%) and without (64%) angina, as well as those with myocardial infarction (61.5%) and peripheral vascular disease (62%).

ConclusionsIn this study, the prevalence of aspirin use in primary prevention was 8.5%. We found that 30% of patients were not taking either antithrombotic or anticoagulation therapy in secondary prevention. In both primary and secondary prevention, the 150 mg dosage was predominant.

As doenças cardiovasculares permanecem uma das principais causas de morbilidade e mortalidade em nível mundial. A administração de baixas doses de ácido acetilsalicílico (AAS) na prevenção secundária de doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica (DCVA) foi claramente estabelecida. Concomitantemente, as recomendações mais recentes não o aconselham na prevenção primária, propondo ser reservado para doentes de alto risco e após uma avaliação risco/benefício. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar a adesão às recomendações europeias para o uso de AAS na prevenção primária e secundária de DCVA nos cuidados de saúde primários.

MétodosA população em estudo correspondeu a indivíduos >50 anos registados em duas unidades de cuidados de saúde primários sem (prevenção primária) e com eventos de DCVA anteriores (prevenção secundária).

ResultadosForam estudados 1262 indivíduos, 720 em prevenção primária e 542 em prevenção secundária. Verificámos que 61 dos indivíduos (8,5%) estavam sob terapia com AAS em prevenção primária, com uma predominância da dose de 150 mg (57%). Em prevenção secundária, 195 dos doentes (27%) estavam a realizar ASA exclusivamente, com uma predominância da dose de 150 mg (52%) e 166 dos doentes (31%) não estavam sob qualquer agente antitrombótico ou anticoagulante. A dosagem de 100 mg foi predominante em doentes com doença cardíaca isquémica com (64%) e sem (64%) angina, enfarte agudo do miocárdio (61,5%) e doença vascular periférica (62%).

ConclusõesNeste estudo, a prevalência do uso de AAS na prevenção primária foi de 8,5%. Identificámos 30% de doentes que não cumpriam terapia antitrombótica ou anticoagulante em prevenção secundária. Quer em prevenção primária como secundária, o uso da dosagem de 150 mg foi predominante.

Cardiovascular (CV) disease remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, with ischemic heart disease at the forefront, accounting for 16% of deaths worldwide in 2019.1

Several studies have shown reductions in CV events and total mortality in secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) with the administration of low doses (75–100 mg/day) of aspirin, clearly establishing the benefit of its use.2,3

On the other hand, the evidence of its benefit in primary prevention of ASCVD is not robust, with differences in the recommendations from various agencies and societies. In particular, the Portuguese Directorate-General of Health (DGS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) do not recommend the use of aspirin in individuals without CV disease, due to the risk of severe bleeding.4,5 The position of the ESC is supported by contemporary studies showing results in moderate-risk patients (ARRIVE),6 people with diabetes (ASCEND)7 and healthy individuals over 70 years of age (ASPREE),8 which have not demonstrated reductions in mortality (CV or all-cause).9 In 2019 these studies also led the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association10 to reflect these results and to recommend the use of aspirin for a smaller number of patients compared to previous guidelines by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).11 The USPSTF is currently presenting a draft recommendation that also points in the same direction.12 The American Diabetes Association states that the use of aspirin should be reserved for high-risk patients after a risk/benefit assessment through a process of shared decision-making.13

There is evidence that daily doses of 30 mg of aspirin inhibit platelet function after one week, although some clinical conditions are associated with suboptimal inhibition. Thus, daily dosages of 75–100 mg, although exceeding what is necessary, accommodate individual variability.14

As mentioned above, the CV benefit must be balanced against the risk of bleeding (especially gastrointestinal) that is associated with this therapy.15 It has been observed that increasing the dose of aspirin not only does not increase the benefit in reducing adverse events, but also increases the risk of bleeding.16–18 Therefore, the dosage recommendations of this therapy should be respected.

The aim of this study was to assess adherence to European guidelines for the use of aspirin in primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD in two primary health care units, including its use, factors associated with its use and dosages prescribed.

MethodsStudy designWe performed a retrospective, observational, cross-sectional, analytical study by consulting electronic clinical records (SClínico®), Módulo de Informação e Monitorização das Unidades Funcionais (MIM@UF) and Bilhete de Identidade dos Cuidados de Saúde Primários (BI-CSP). Therapeutic adherence was validated through the PEM® (Prescrição Eletrónica de Medicamentos, SPMS, EPE) platform by consulting drug dispensing in the previous year.

The study was approved by the Health Ethics Committee of the Lisbon and Tagus Valley health authority.

PopulationThe study population consisted of users registered at the S. Martinho de Alcabideche Family Health Unit (USFSMA) of the Cascais Health Center Group and at the S. Julião Family Health Unit (USFSJ) of the West Lisbon and Oeiras Health Center Group. Patients were divided into two groups with the following characteristics.

The primary prevention of ASCVD group were those over 50 years of age who did not present any of the International Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2) codes for ischemic heart disease with angina (K74), acute myocardial infarction (K75), ischemic heart disease without angina (K76), transient cerebral ischemia (K89), stroke/cerebrovascular accident (K90), cerebrovascular disease (K91) or atherosclerosis/peripheral arterial disease (K92) as an active or inactive problem.

The secondary prevention of ASCVD group were defined as those with at least one of the above ICPC-2 codes listed as an active or inactive problem.

The sample size was determined by defining a standard error of 5% and a confidence level of 95%. The sample size was calculated using the Sample Size Calculator® application, to provide a simple random sample for the primary prevention group and a proportional stratified sample for the secondary prevention group. After the population was sorted by National Health Service (NHS) user number, the sample was generated using the RANDOM.ORG® application.

Data collected in both groups included NHS user number, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), ICPC-2 coding of ischemic heart disease with angina (K74), acute myocardial infarction (K75), ischemic heart disease without angina (K76), uncomplicated hypertension (K86), transient cerebral ischemia (K89), stroke/cerebrovascular accident (K90), cerebrovascular disease (K91), atherosclerosis/peripheral arterial disease (K92), obesity (T82), diabetes insulin dependent (T89), diabetes non-insulin-dependent (T90), lipid disorder (T93), and tobacco abuse (P17). We also collected the ICPC-2 codes for peptic ulcer (D86) and purpura/coagulation defect (B83), current aspirin use, corticosteroid therapy, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, use of anticoagulants, previous adverse reaction to aspirin, glomerular filtration rate, Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), antihypertensive therapy and lipid-lowering therapy.

Risk factors for ASCVD (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity and smoking) were recorded according to the ESC guidelines on CV disease prevention19 and individual clinical records.

Exclusion criteria for the primary prevention group were absence of data, sporadic use or non-use of aspirin, history of previous CV events, and presence of contraindications to the use of aspirin. Exclusion criteria for the secondary prevention group were the same, plus a history of hemorrhagic stroke.

Statistical analysisData were collected and analyzed using Microsoft Excel®, FileMakerPro® and Jamovi®. Continuous variables were summarized as mean, minimum and maximum, and categorical variables as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies.

ResultsThe study sample included a total of 720 individuals in the primary prevention group (357 from USFSMA and 363 from USFSJ) and 542 individuals in the secondary prevention group (236 from USFSMA and 306 from USFSJ).

In the primary prevention group, mean age was 69 years for USFSMA (minimum 50 years, maximum 97 years) and 67 years for USFSJ (minimum 50 years, maximum 96 years). In the secondary prevention group, the mean age of the sample was higher: 72 years for USFSMA (minimum 42 years, maximum 94 years,) and 77 years for USFSJ (minimum 37 years, maximum 108 years).

In the primary prevention group the majority were women (60.5% in USFSMA and 63.6% in USFSJ), while the opposite was true in the secondary prevention group, with 59.3% and 52% men in USFSMA and USFSJ, respectively. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Primary prevention group (n=720) | Secondary prevention group (n=542) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USFSMA | USFSJ | Total | USFSMA | USFSJ | Total | |

| Mean age, years | 69 | 67 | 68 | 72 | 77 | 75 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 141 (39.5) | 132 (36.4) | 273 (38) | 140 (59.3) | 159 (52) | 299 (55.2) |

| Female | 216 (60.5) | 231 (63.6) | 447 (62) | 96 (40.7) | 147 (48) | 243 (44.8) |

| Risk factors, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 119 (33.3) | 72 (19.8) | 191 (26.5) | 96 (40.7) | 89 (29.1) | 185 (34.1) |

| Hypertension | 274 (76.7) | 243 (67) | 517 (71.8) | 208 (88.1) | 261 (85.3) | 469 (86.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 266 (74.5) | 245 (67.5) | 511 (71) | 173 (60.5) | 262 (85.6) | 435 (80.3) |

| Obesity | 144 (40.3) | 99 (27.3) | 243 (33.8) | 84 (35.6) | 91 (29.7) | 175 (32.3) |

| Smoking | 45 (12.6) | 51 (14) | 96 (13.3) | 32 (13.6) | 34 (11.1) | 66 (12.2) |

| CV risk, n (%) | ||||||

| Very high | 158 (44.2) | 80 (22) | 238 (33.1) | – | ||

| High | 41 (11.5) | 70 (19.3) | 111 (15.4) | – | ||

| Moderate | 136 (38.1) | 177 (48.8) | 313 (43.5) | – | ||

| Low | 22 (6.2) | 36 (9.9) | 58 (8.1) | – | ||

| ASCVD categorya, n (%) | ||||||

| Ischemic heart disease with angina | – | 10 (31.3) | 18 (39.1) | 28 (35.9) | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction | – | 22 (59.5) | 4 (44.4) | 26 (56.5) | ||

| Ischemic heart disease without angina | – | 16 (47.1) | 20 (37) | 36 (40.9) | ||

| Transient cerebral ischaemia | – | 2 (28.6) | 3 (50) | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Stroke/cerebrovascular accident | – | 19 (32.8) | 9 (52.9) | 28 (37.3) | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | – | 4 (30.8) | 17 (28.8) | 21 (29.2) | ||

| Atherosclerosis/peripheral vascular disease | – | 17 (30.9) | 34 (29.6) | 51 (30) | ||

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CV: cardiovascular; USFSJ: S. Julião Family Health Unit; USFSMA: S. Martinho de Alcabideche Family Health Unit.

With regard to the prevalence of CV risk factors in the primary prevention group, 33.3% (USFSMA) and 19.8% (USFSJ) had a diagnosis of diabetes, 76.7% (USFSMA) and 67% (USFSJ) had hypertension, 74.5% (USFSMA) and 67.5% (USFSJ) had dyslipidemia, 40.3% (USFSMA) and 27.3% (USFSJ) were obese and 12.6% (USFSMA) and 14% (USFSJ) were smokers (Table 1). In addition, 55.7% (USFSMA) and 41.3% (USFSJ) of the sample were classified as having high or very high CV risk (Table 1).

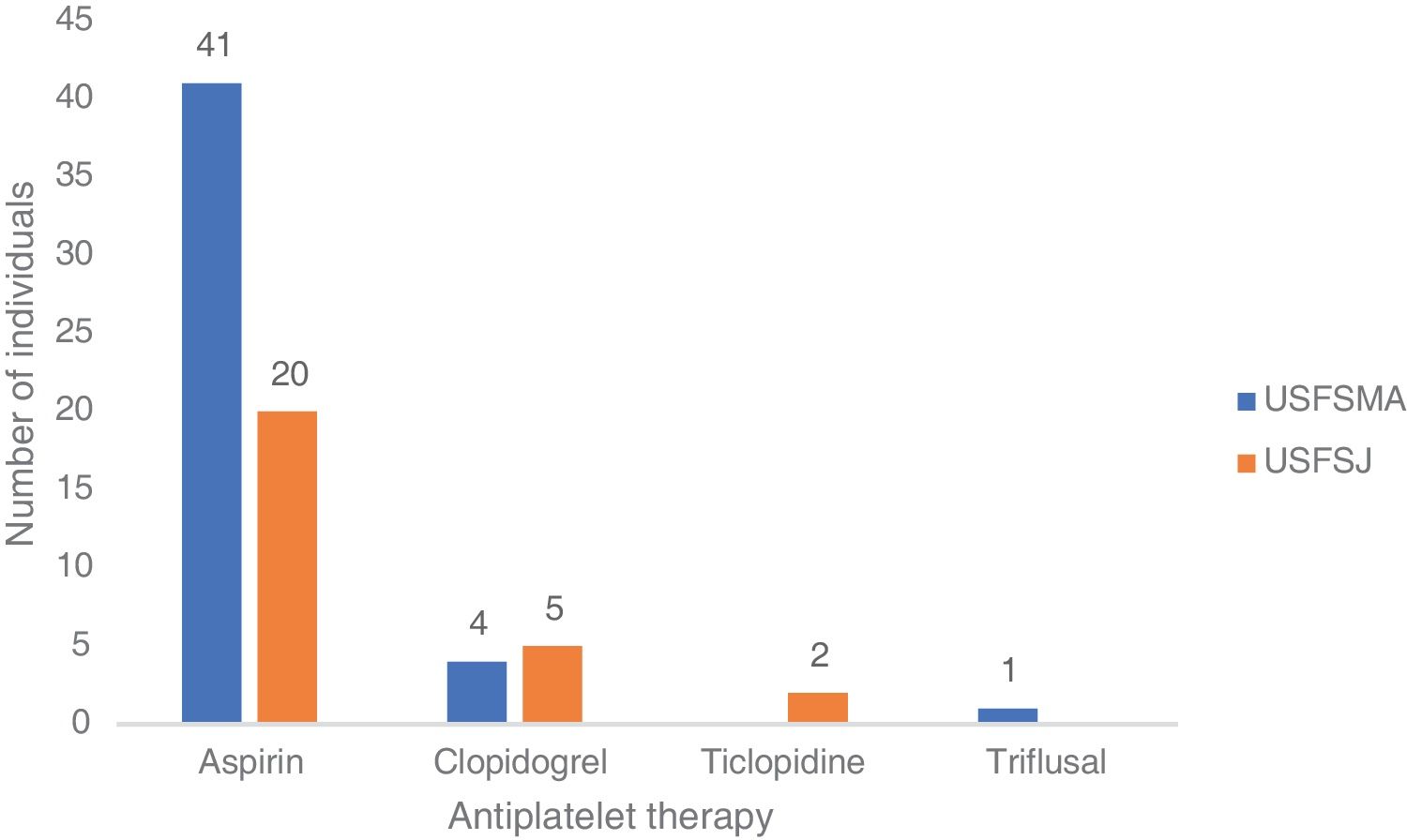

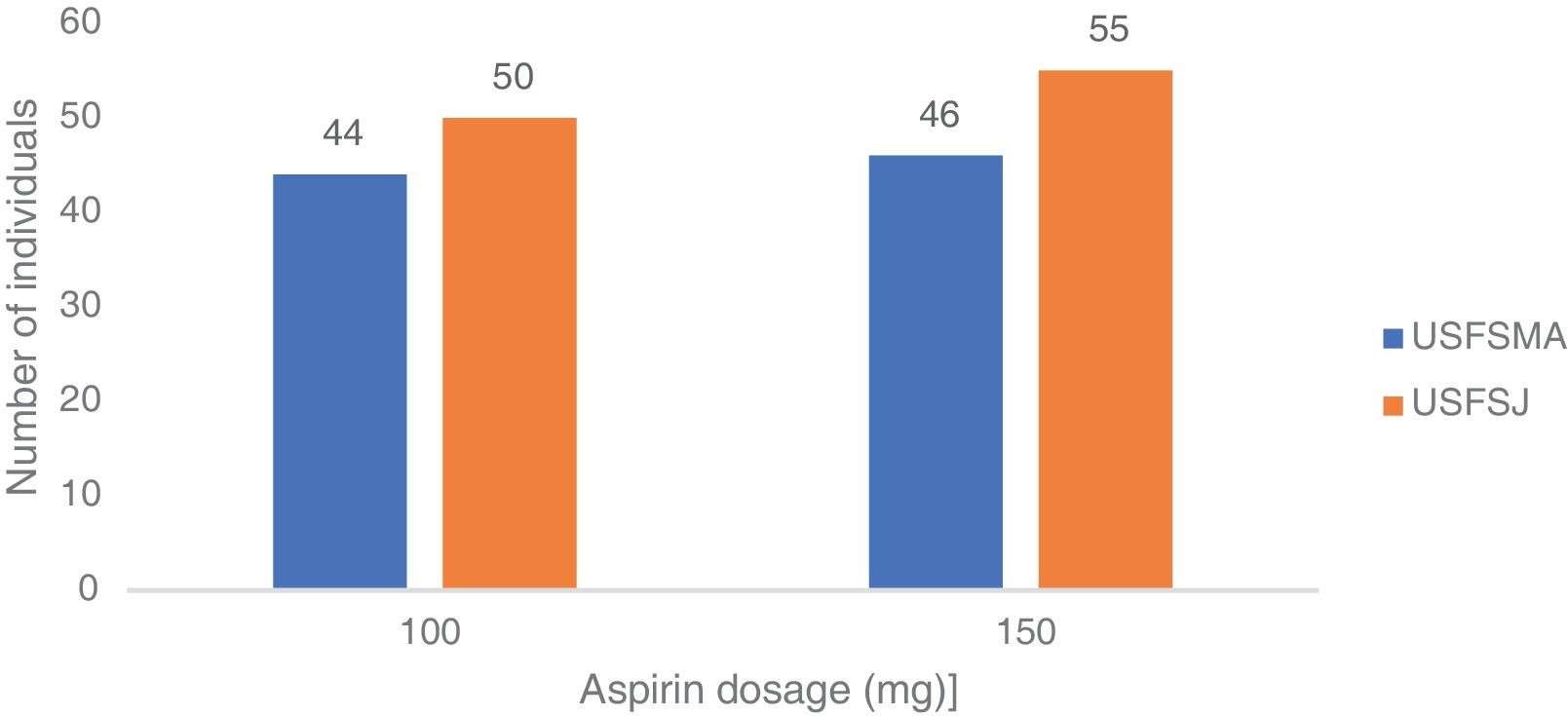

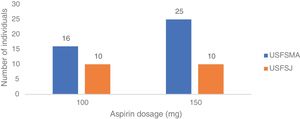

In terms of aspirin therapy, 11.5% of participants (n=41) at USFSMA and 5.5% (n=20) at USFSJ were taking this medication in primary prevention (Figure 1). Also, more than 50% of individuals taking aspirin in primary prevention in both units had high or very high CV risk, hypertension being the most prevalent risk factor (data not shown).

Secondary prevention groupIn terms of CV risk factors in the secondary prevention group, 40.7% at USFSMA and 29.1% at USFSJ had a diagnosis of diabetes, 88.1% (USFSMA) and 85.3% (USFSJ) had hypertension, 60.5% (USFSMA) and 85.6% (USFSJ) had dyslipidemia, 35.6% (USFSMA) and 29.7% (USFSJ) were obese and 13.6% (USFSMA) and 11.1% (USFSJ) were smokers (Table 1).

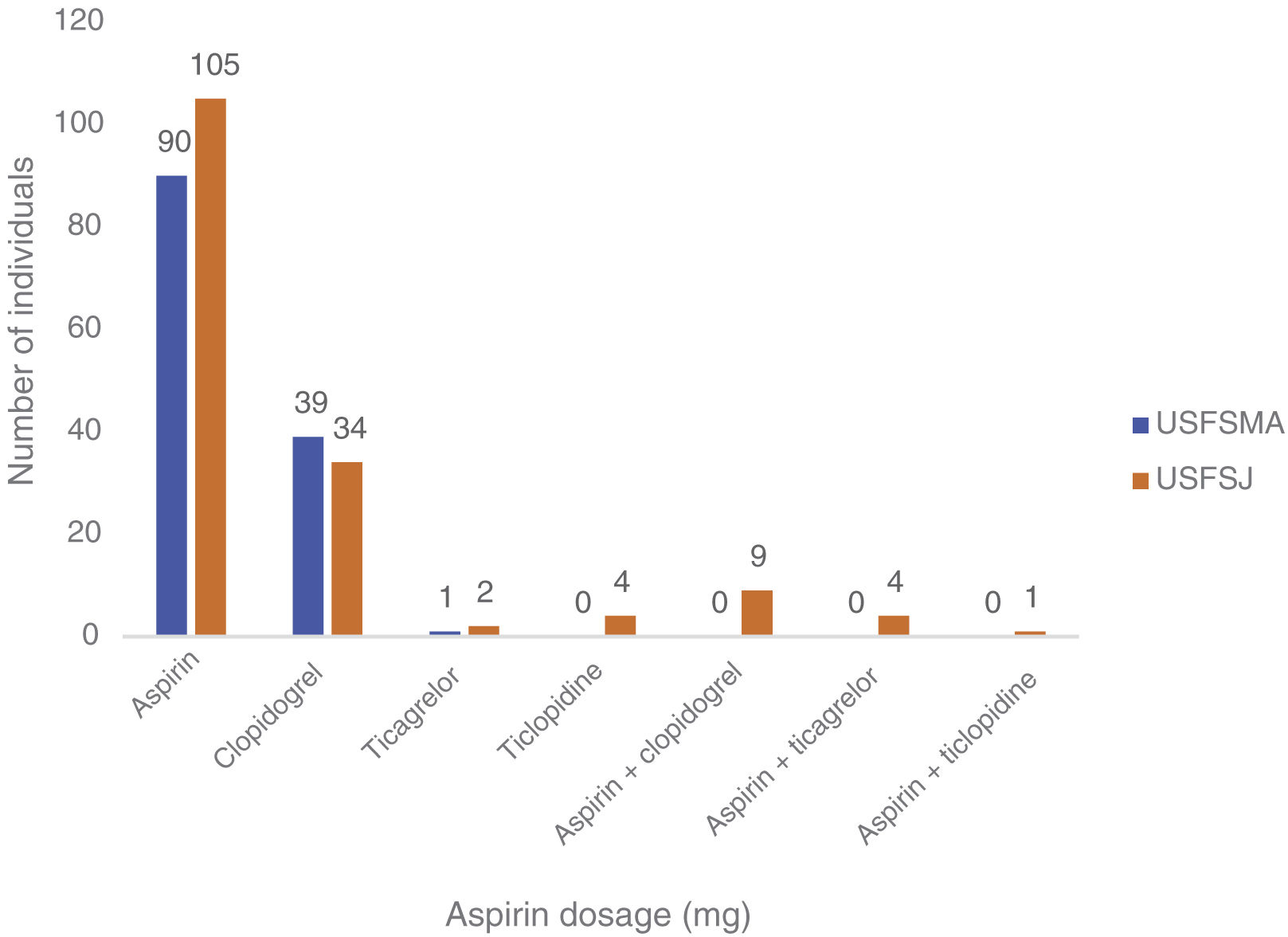

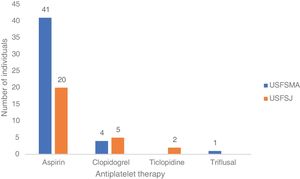

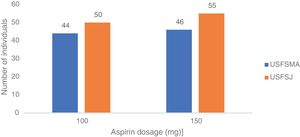

In this group, over 50% in both units were under antiplatelet therapy. Of these, 39% (USFSMA) and 34% (USFSJ) were under aspirin therapy only, with 16.5% and 11.1% in USFSMA and USFSJ, respectively, taking clopidogrel (Figure 2). It should be noted that 17% and 15.4% (USFSMA and USFSJ, respectively) of patients were under anticoagulant therapy (data not shown), leaving almost 30% without any protective therapy.

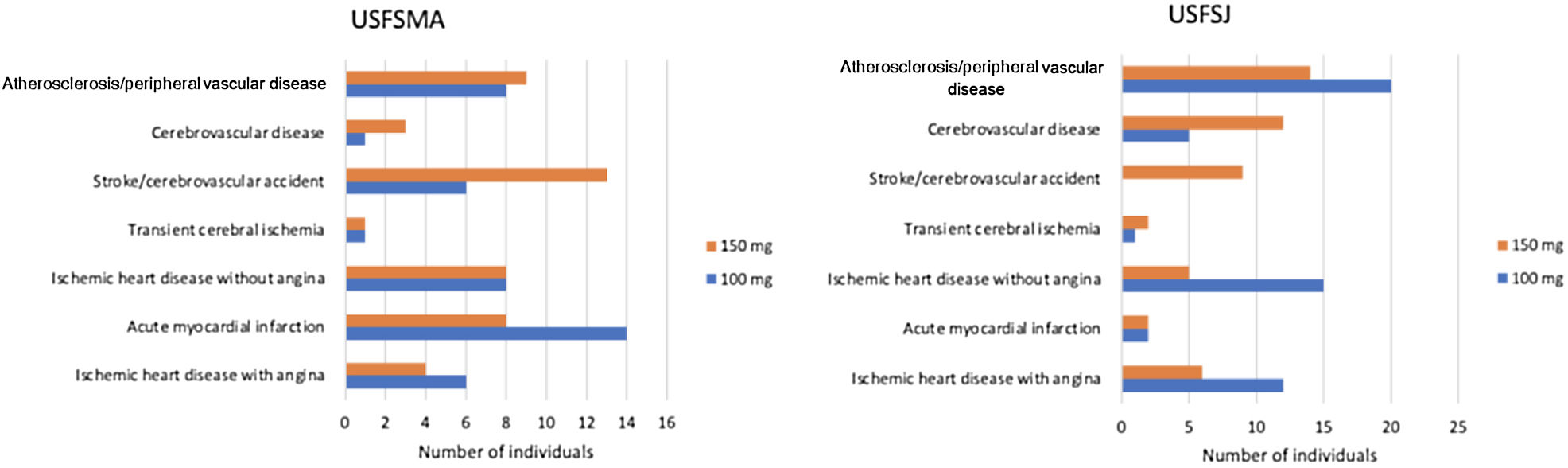

Regarding therapeutic indications for aspirin therapy, we observed that the highest proportion of patients under aspirin therapy (over 50%) had coding for acute myocardial infarction, followed by those with ischemic heart disease without angina (Table 1).

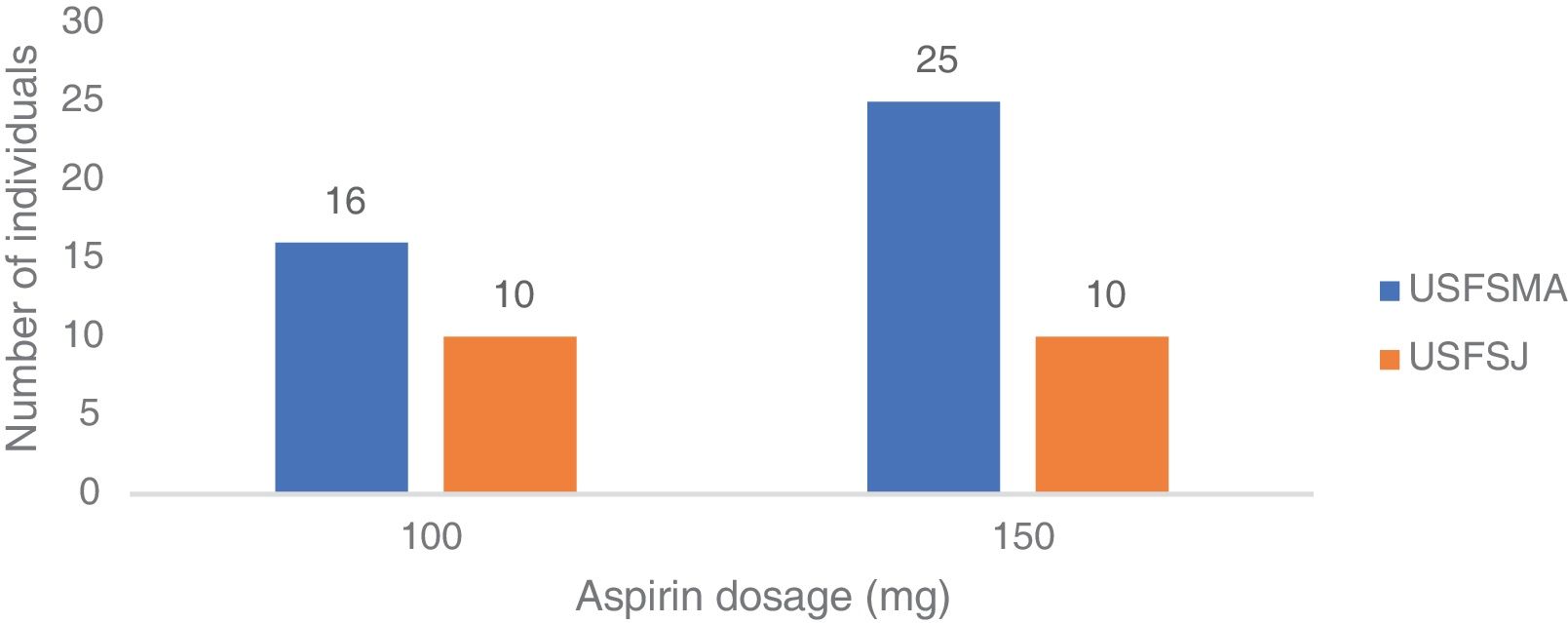

Aspirin dosagesRegarding the dosages prescribed in primary prevention, there was a predominance of the 150 mg dose in USFSMA and equal proportions of 100 mg and 150 mg in USFSJ (Figure 3).

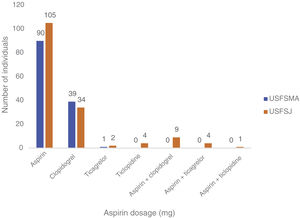

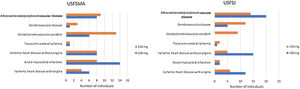

In the secondary prevention group, approximately equal proportions of both dosages were seen in the two units (Figure 4). When considering the dose prescribed by therapeutic indication, the 100 mg dosage was prescribed most frequently in patients with ischemic heart disease with (64%) and without (64%) angina, followed by myocardial infarction (61.5%) and peripheral vascular disease (62%) (Figure 5). By contrast, the 150 mg dosage was more common in patients with coding for stroke or cerebrovascular disease (Figure 5).

The present study shows that aspirin is used in 8.5% of individuals in primary prevention of ASCVD and that 31% of patients in secondary prevention of ASCVD were not receiving any antithrombotic or anticoagulant agent. To our knowledge this is the first study on adherence to the European guidelines for the use of aspirin in primary health care in Portugal.

In the primary prevention group, there was a higher prevalence of CV risk factors (with the exception of smoking) in individuals attending USFSMA. This may reflect the characteristics of the population served by this unit and not a coding bias, given that both USFSMA and USFSJ are model B units (constituted in 2012 and 2007, respectively) and as such, would be expected to have very similar procedures.

As could be predicted, given the higher prevalence of CV risk factors in USFSMA, a greater number of individuals were classified at high or very high risk in this unit. The number of individuals under aspirin in primary prevention was lower than reported in previous studies,20,21 but even so, this was roughly double at USFSMA compared to USFSJ, which may reflect prescribing patterns that started earlier, even before the beginning of the unit's activity. Of these, more than 50% of the individuals in both units had high or very high CV risk, leaving at least 40% at low or moderate risk without any indication for this therapy. Also for the same group, about 50% of individuals receiving aspirin in primary prevention in both units were 70 years old or older, which contrasts with the most recent guidelines, but similar to that observed in the USA.21 It is possible that a sufficiently long time has not yet passed to enable these recommendations to be put into practice.

In the group of individuals with previous CV events, it was found that the most prevalent risk factor was hypertension, followed by dyslipidemia. At USFSMA there was a higher prevalence of all risk factors compared to USFSJ, with the exception of dyslipidemia; as in the primary prevention sample, this may reflect characteristics of the population served by the Cascais council unit. More than half of the sampled individuals with an indication for antiplatelet therapy were actually taking it; if these users are considered together with those on anticoagulation therapy (data not shown), about 30% of these individuals are not taking any therapy, which should also be analyzed (the reasons for non-use may be related to under-prescription or non-adherence to therapy, for example). Among individuals under aspirin therapy in secondary prevention, the therapeutic indication with the highest number of users was acute myocardial infarction, followed by stroke at USFSMA; in USFSJ, the therapeutic indication with the largest number of individuals taking aspirin was peripheral vascular disease, followed by ischemic heart disease without angina. These differences may reflect different coding profiles between the two units, including failure to deactivate codes referring to acute events and subsequently to code chronic illness. In addition, the therapeutic indications for cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease were those with the lowest proportion of patients taking the recommended therapy, which may reflect therapeutic inertia for these conditions or the need to update or review the indications for aspirin.

With regard to the prescribed aspirin dosages, the two doses available in Portugal (100 and 150 mg) were used, with a preference for 150 mg in USFSMA. This could be explained by the state subsidization of the drug at this dosage, which however exceeds the dosages recommended in the different guidelines, and may contribute to the occurrence of adverse effects, especially undesirable bleeding. Also, the 100 mg dosage, although approximately 50% more expensive than the subsidized one, has a cost of approximately €1.50.

When the aspirin dosages used in secondary prevention are analyzed, the two dosages were prescribed in equal proportions in the two units under study; however, when dosages are analyzed by therapeutic indication, there was a higher prevalence of the 100 mg dosage in the context of acute myocardial infarction and ischemic heart disease with angina at USFSMA, and in ischemic heart disease with and without angina, and peripheral vascular disease at USFSJ. This suggests the possibility of therapeutic introduction of this dosage in these conditions by other specialties (particularly cardiology) that would be later renewed at the level of primary health care, which may not happen for other indications.

Finally, the limitations of our study should be taken into account. First, only two units were analyzed, thereby reflecting only their particular situation, which does not allow these observations to be extrapolated to wider contexts. Secondly, this analysis is closely dependent on the coding and medical records of the units under study, which necessitates an assessment of the therapies prescribed and the prevalence of the relevant diseases. Information was unavailable regarding other conditions for which aspirin may be indicated, such as revascularization or high coronary artery calcium, although these patients may have been coded within the groups under analysis.

Also, aspirin intake may be underestimated since the drug can be obtained without a prescription.

ConclusionsDespite the widespread use of aspirin in the prevention of CV disease, there are few studies that analyze its use, particularly in Portugal. Additionally, with current guidelines, it is crucial to assess aspirin use patterns to inform the interventions required to incorporate new recommendations into clinical practice.

In this study, we have found that 61 individuals (8.5%) were under aspirin therapy in primary prevention, with a predominance of the 150 mg dosage (57%). In secondary prevention, 31% of patients were not under any antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy. In both primary and secondary prevention, the 150 mg dosage was predominant.

It should be noted that the most recent guidelines explicitly warn against the use of aspirin in primary prevention in individuals aged ≥70 years, and that such use should be discontinued and discouraged, given the increased bleeding risk.10 Likewise, the dosage used should be subject to review, which could lead to preventable adverse bleeding events, given that the 150 mg dosage is still widely used in both primary and secondary prevention of CV disease. In this context, the most recent recommendations for the treatment of peripheral vascular disease should also be taken into consideration, as they include concomitant antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy,22 while emphasizing that the lowest effective dose of aspirin should be used.

The economic burden arising from prescribing a medication that may or may not be subsidized by the State should be taken into account when assessing these recommendations. Ideally, economic decisions by the State should be revised and implemented together with the updated medical practice guidelines.

FundingThe authors have no funding sources to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.