We describe a rare case of acute myocardial infarction secondary to paradoxical embolism complicating acute pulmonary embolism. A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with chest pain. The physical examination was unremarkable except for oxygen saturation of 75%, and the electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads. Urgent coronary angiography showed a distal occlusion of the right coronary artery and multiple thrombi were aspirated. Despite relief of chest pain and electrocardiogram normalization, her oxygen saturation remained low (90%) with high-flow oxygen by mask. The transthoracic echocardiogram showed a mass in the left atrium and dilatation of the right chambers, while the transesophageal echocardiogram showed a thrombus attached to the interatrial septum in the region of the foramen ovale. Color flow imaging was consistent with a patent foramen ovale. Thoracic computed tomography angiography documented thrombi in both branches of the pulmonary trunk. After five days on anticoagulation, the patient underwent surgical foramen ovale closure.

Descreve-se um caso raro de enfarte agudo do miocárdio por embolia paradoxal em contexto de tromboembolismo pulmonar agudo. Uma mulher de 44 anos recorreu à urgência por dor torácica. A observação foi normal com exceção de saturação periférica de 75%. O electrocardiograma mostrou supradesnivelamento do segmento ST nas derivações inferiores. Realizou-se cateterismo urgente que mostrou coronária direita ocluída distalmente, tendo sido aspirados múltiplos trombos. Verificou-se alívio da dor e desaparecimento do supradesnivelamento de ST. No entanto, a saturação periférica mantinha-se baixa apesar de aporte com oxigénio. O ecocardiograma transtorácico mostrou massa auricular esquerda e dilatação das cavidades direitas. O ecocardiograma transesofágico revelou um trombo no septo interauricular, na região do foramen ovale. O estudo por Doppler-cor foi compatível com foramen ovale patente. A angio-tomografia computorizada do tórax documentou trombos nos ramos principais da artéria pulmonar. Após cinco dias de anticoagulação a doente foi submetida a cirurgia cardíaca e o foramen ovale encerrado.

Paradoxical embolism is an uncommon situation, accounting for less than 2% of all arterial emboli.2 We describe a rare case of acute myocardial infarction secondary to paradoxical embolism complicating acute pulmonary embolism.

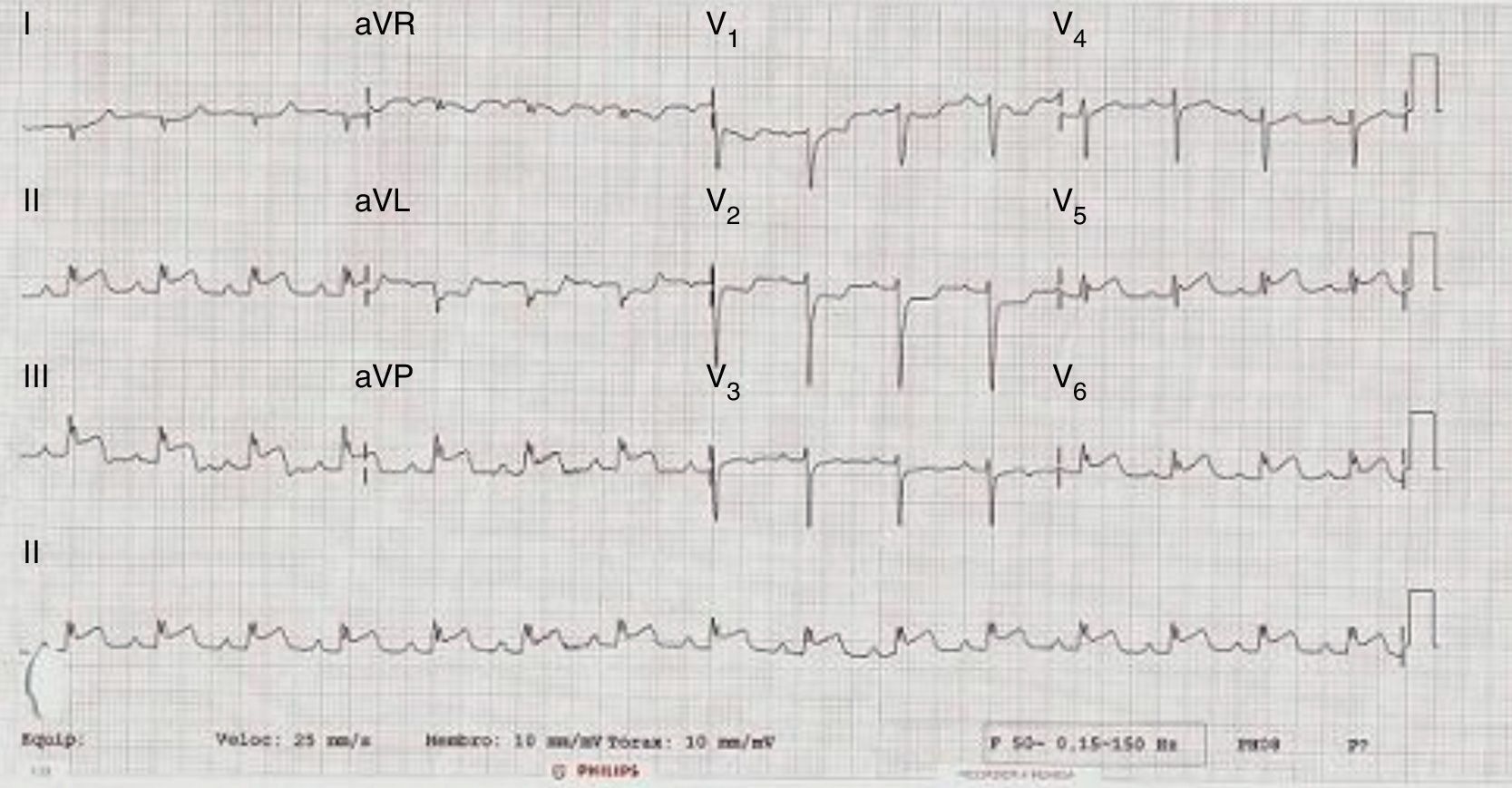

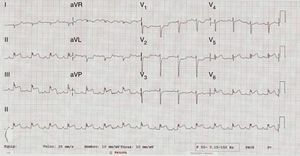

Case reportA 44-year-old woman, taking oral contraceptives, with a medical history of type 2 diabetes and mild obesity, presented with an acute episode of non-radiating substernal chest pain, which aroused her from sleep. She also suffered dyspnea, nausea, diaphoresis and transient loss of consciousness before reaching the emergency department two and a half hours later. Her vital signs were blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, heart rate 85 beats per minute, respiratory rate 23 cycles per minute and oxygen saturation 75% in room air. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm and ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, V5 and V6 (Figure 1). She was diagnosed with acute inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) and was admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU).

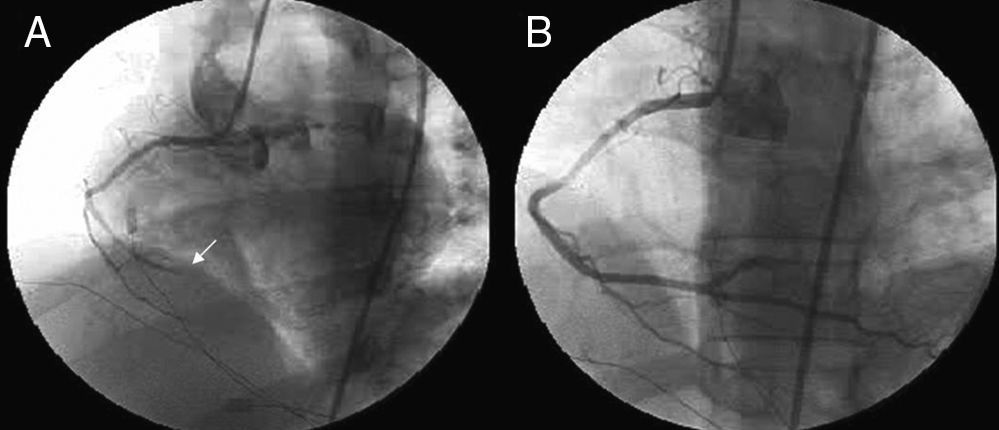

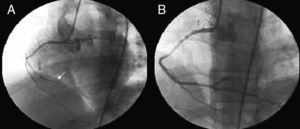

In the CCU screening transthoracic echocardiography excluded mechanical complications of MI and showed a non-dilated left ventricle, with good global systolic function, akinesia of the inferior wall and dilatation of the right cardiac chambers. In view of a possible inferior MI with extension to the right ventricle, the patient underwent emergency coronary angiography that confirmed an occlusion (TIMI flow 0) of the distal right coronary artery (Figure 2A). The other coronary arteries were normal. An Export® aspiration catheter (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) was advanced into the right coronary artery and multiple thrombi were aspirated. After thrombectomy, TIMI flow 3 was documented, but residual stenosis was noted in the distal right coronary artery and a bare-metal stent was implanted (Figure 2B).

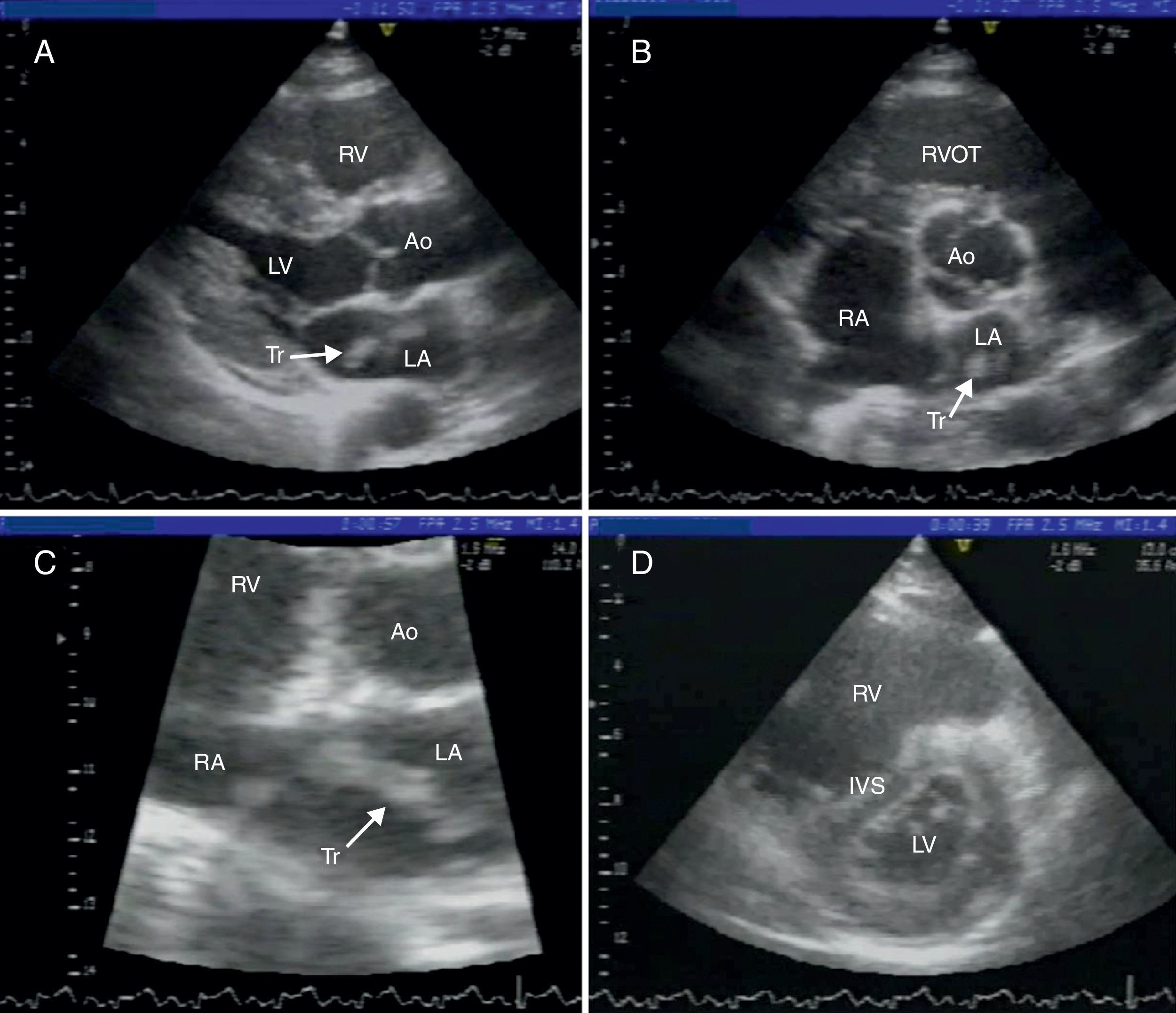

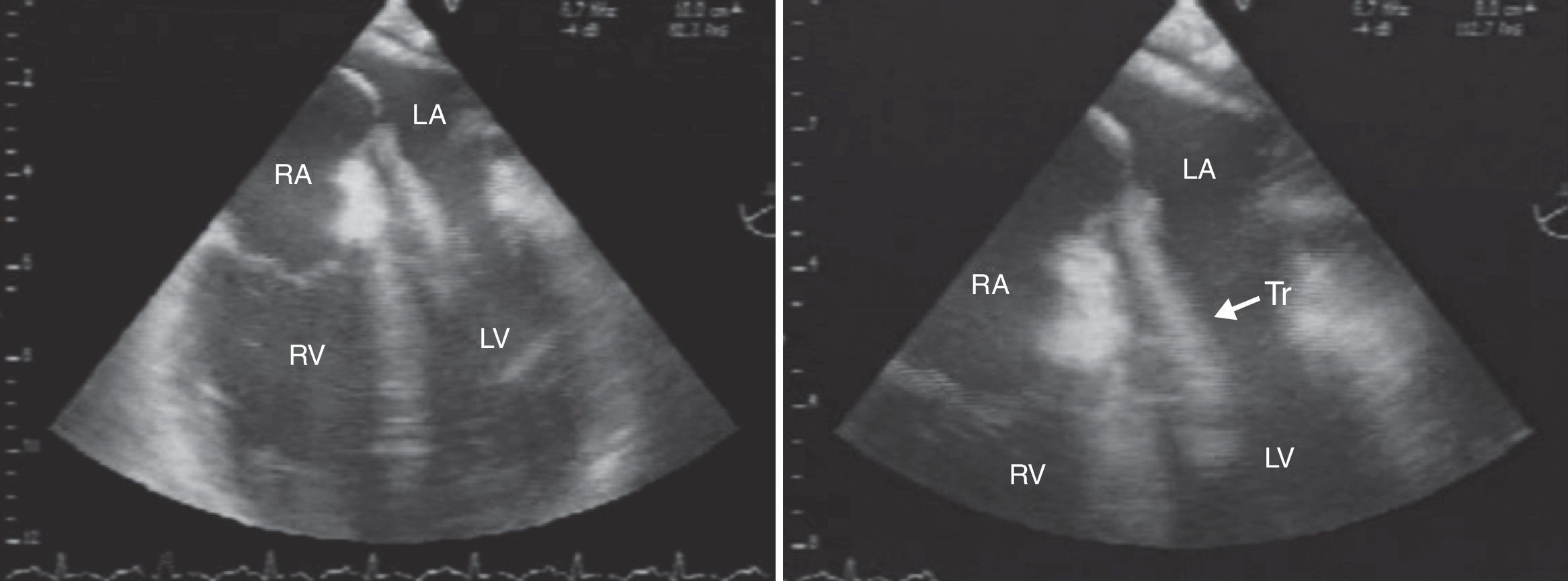

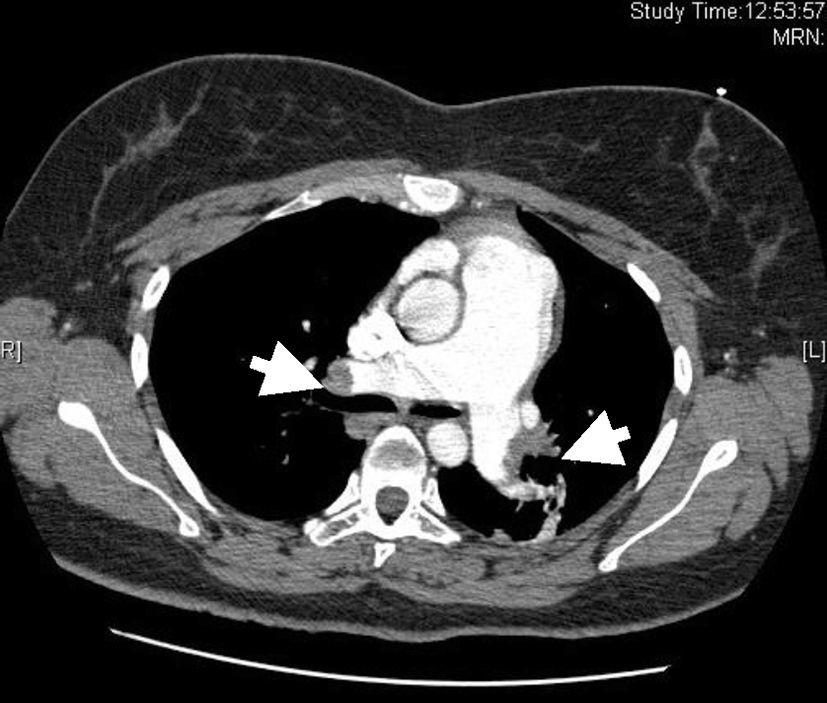

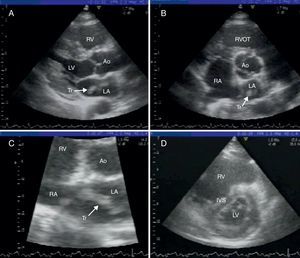

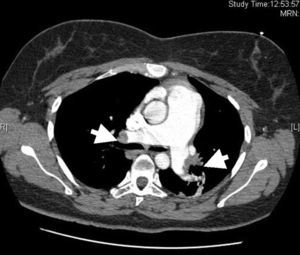

On return to the CCU, the patient experienced complete relief of chest pain and ST-segment normalization on the ECG. Nonetheless, her oxygen saturation level was still 90% despite high-flow oxygen by mask. A full transthoracic echocardiogram examination was then performed. A mass consistent with a thrombus was noted in the left atrium, appearing to arise from a redundant interatrial septum, while the right ventricle was moderately dilated with positive McConnell sign and the interventricular septum was displaced into the left ventricle, which was D-shaped in short-axis view (Figure 3). The pulmonary artery was dilated and the flow across the pulmonary valve suggested severe pulmonary hypertension with pulmonary artery systolic pressure estimated at 70 mmHg. In apical 4-chamber view, color flow imaging of the interatrial septum showed a right-to-left shunt. It was then decided to perform transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to better characterize the relationship of the mass with the interatrial septum and its embolic potential, and also to look for masses in the right atrium. TTE showed a long thrombus that appeared to be attached to the atrial septum in the region of the foramen ovale. Color flow imaging was consistent with a patent foramen ovale (PFO) and the atrial septum was aneurysmatic. The thrombus had a snake-like movement inside the left atrium and its distal end was freely mobile, prolapsing through the mitral valve (Figure 4). No mass was observed in the right atrium or pulmonary arteries. Thoracic computed tomography angiography revealed bilateral thrombi in the main and lobar branches of the pulmonary artery (Figure 5).

(A) parasternal long-axis view; (B) parasternal short-axis view of the aortic valve; (C) zoom of short-axis view; (D) D-shaped left ventricle. Ao: aorta; IVS: interventricular septum; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle; RVOT: right ventricular outflow tract; Tr: thrombus.

According to the criteria suggested by Johnson,1 the patient had a definitive diagnosis of paradoxical embolism: a thrombus crossing an intracardiac defect was seen during echocardiography in the presence of an arterial embolus. The therapeutic options for paradoxical embolism are still a matter of debate. In our case, cardiothoracic surgeons were consulted and considered the operative risk to be too high, and the patient did not consent to surgical intervention. Due to her stable clinical condition and the absence of neurological signs, we decided to maintain her on full-dose anticoagulation with enoxaparin and double antiplatelet therapy. Venous Doppler echocardiography of the lower limbs was normal. Five days later the transthoracic echocardiogram was repeated; no reduction was noted in the size of the left atrial thrombus, whereupon the cardiothoracic surgeons were again consulted and it was decided to operate. The same day, she was transferred to a surgical center and surgery was performed: an atrial aspiration system was placed in the right superior pulmonary vein, the right atrium and the interatrial septum were opened and the left atrium was inspected. No thrombus was seen in any cardiac chamber or vessel and the PFO was sutured. The patient's postoperative course was remarkably stable and the transthoracic echocardiogram before hospital discharge showed no signs of right ventricular overload. She was discharged home anticoagulated with warfarin and advised to discontinue oral contraceptives. Further laboratory testing showed no thrombophilia status.

DiscussionAs proposed by Johnson, the diagnosis of paradoxical embolism can be: 1) definitive – when made at autopsy or when a thrombus is seen crossing an intracardiac defect during echocardiography in the presence of an arterial embolus; 2) presumptive – when there is systemic arterial embolus in the absence of a left-sided cardiac or proximal arterial source plus a right-to-left shunt at some level plus venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolus; 3) possible – only arterial embolus and PFO detected.1 In our patient we had a definitive diagnosis of paradoxical embolism, as noted above. Although in situ thrombus formation over a ruptured plaque cannot be definitively excluded in our patient, the angiographic appearance of the thrombus was most consistent with coronary embolization. The patient's increased risk of venous thrombosis can be explained by oral contraceptive use. An interesting point is that when the left atrium was opened during surgery no thrombus was seen, even though the transthoracic echocardiogram on the same day had shown no reduction in the size of the mass. The most probable explanation is aspiration of the mass by the atrial aspiration system put in place before the left atrium was opened.

Most cases of paradoxical embolism have been associated with PFO.2,3 Although PFO is a frequent finding in the general population, paradoxical embolism is an uncommon event.2,3 Paradoxical embolism in a coronary artery is a recognized clinical entity, but is rare and usually definitively established only at autopsy.4,5 Impending paradoxical embolism, in which a thrombus is seen straddling an interatrial defect, is also a rare diagnosis. Finally, paradoxical embolism with coronary embolization and visualization of the thrombus crossing a PFO is even rarer, with very few cases described in the literature.4,6–9

The vast majority of patients with paradoxical embolism present with symptoms of pulmonary embolism (82%) or arterial embolism (25%). Only 16% of patients present with findings suggestive of both venous and arterial embolism.3 Pulmonary embolism (or any condition that raises right atrial pressure) is frequently implicated in the increased right heart pressures that set the stage for right-to-left shunting via a PFO.4,7,9

TEE is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management when paradoxical embolism is suspected.10 TEE study with color Doppler and contrast echocardiography is the most sensitive diagnostic technique for diagnosing PFO.11 The four cases described in the literature of antemortem diagnosis of paradoxical coronary embolism with visualization of a thrombus crossing a PFO used TEE to establish the diagnosis. TEE is the ideal diagnostic procedure in the setting of suspected myocardial infarction of thromboembolic origin because of its ability to visualize both paradoxical emboli and the proximal portions of the coronary arteries.4,6,7

Mortality in paradoxical embolism with entrapped embolus is estimated at 21%.10 The treatment of paradoxical or impending paradoxical embolism is a clinical dilemma. Acute treatment options include anticoagulation, fibrinolysis or surgical embolectomy. In the presence of a thrombus with a high embolic potential, fibrinolysis carries a high risk of fragmentation and systemic embolization.7,10 In the setting of a thrombus crossing a PFO, thrombolytic therapy has the potential to result in systemic embolization and devastating neurological complications. Surgery also enables simultaneous closure of the PFO.6,7,10 Overall survival appears to be equivalent among the three therapeutic options, although more complications relating to arterial and pulmonary embolization occur with anticoagulation and fibrinolysis. For this reason, anticoagulation followed by surgical embolectomy has been recommended as the optimal therapy, although recommendations for the management of paradoxical embolism are based on small series and isolated case reports. A medical strategy using thrombolytic therapy or heparin therapy alone may have a role in patients at increased surgical risk.3