Coronary artery perforation (CAP) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents prevent blood leakage between struts with a high rate of success. However, they lack elasticity and rapid and correct deployment is difficult. They have also a higher rate of stent restenosis and thrombosis. For these reasons, optimal deployment is essential.

Although severe CAP needs an emergent solution, after stabilizing the patient, intracoronary imaging techniques may be useful to ensure correct expansion and reduce further adverse events.

We present a case that shows the potential role of intravascular ultrasound in the resolution of a CAP.

A perfuração da artéria coronária (PAC) é uma complicação rara, mas potencialmente fatal da intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP). Os stents revestidos com politetrafluoroetileno impedem o leakage do sangue entre os suportes com uma elevada taxa de sucesso. No entanto, a falta de elasticidade e o posicionamento rápido e correto são difíceis. Apresentam também uma taxa mais elevada de reestenose de stent e de trombose. Por este motivo, é fundamental um posicionamento otimizado.

Embora a PAC necessite de uma solução emergente, após estabilizar o doente, as técnicas intracoronárias imageológicas podem ser úteis para assegurar a expansão correta e reduzir eventos adversos adicionais.

Apresentamos um caso que revela o papel potencial da ultrassonografia intravenosa na resolução de uma PAC.

A 69-year-old patient was admitted for unstable angina. The initial ECG showed negative anterior T waves. Physical examination and laboratory tests were normal.

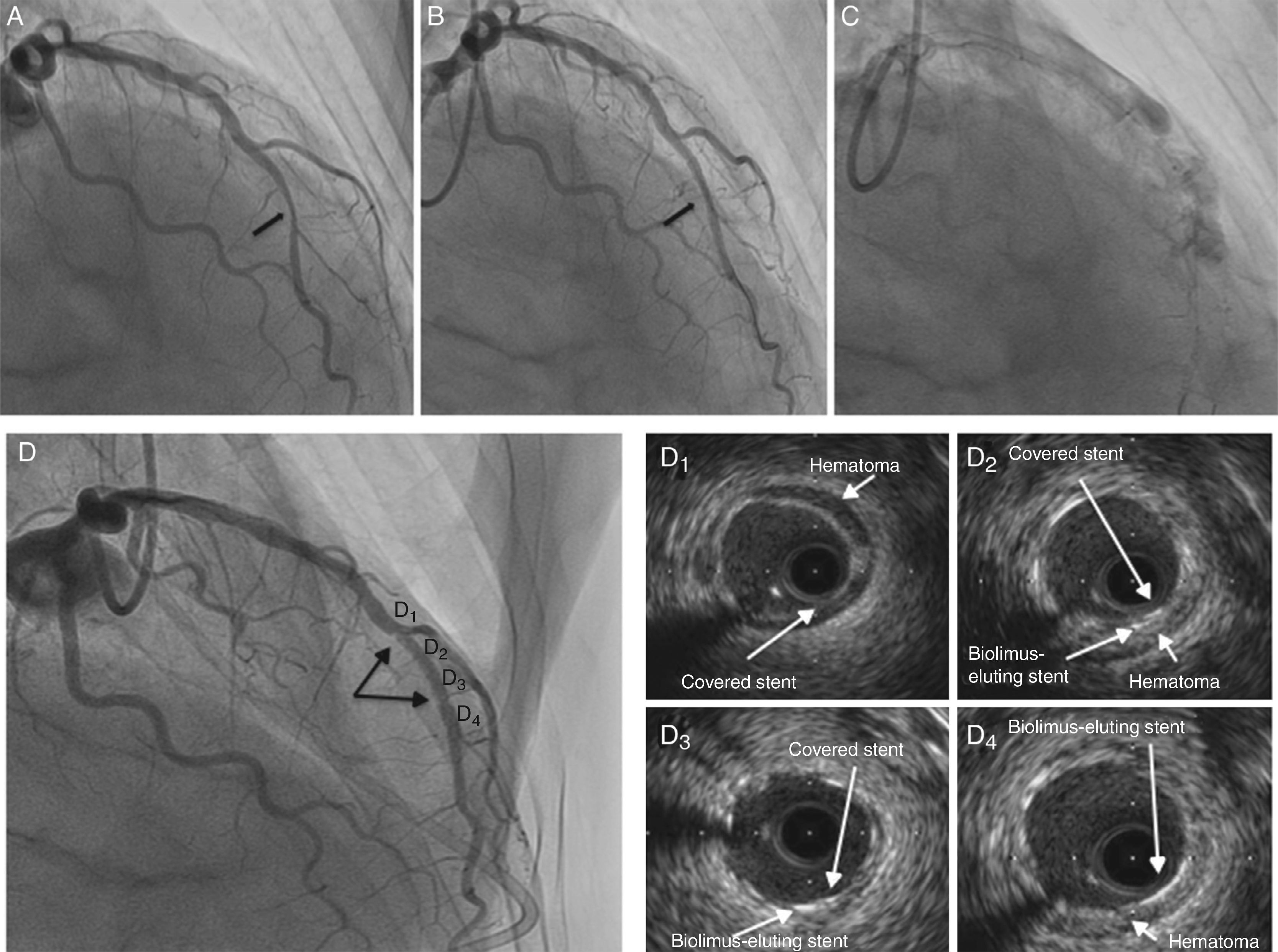

Forty-eight hours later, coronary angiography (CA) was performed. A severe lesion was observed in the mid left anterior descending artery (Figure 1A, arrow). A biolimus-eluting stent (3 mm×18 mm; 20 atm) was implanted, angiographic underexpansion being observed (Figure 1B, arrow). Postdilatation with a non-compliant balloon (3 mm×15 mm; 22 atm) was performed. Immediately, the patient suffered intense chest pain and a coronary artery perforation (CAP) was observed at the proximal edge of the stent (Figure 1C). Bivalirudin was stopped, prolonged balloon inflation proximal to the perforation was performed and a covered stent (2.5 mm×18 mm) was implanted. The patient suffered tamponade and cardiac arrest which required emergent pericardiocentesis and cardiac resuscitation. After stabilization a new CA showed probable underexpansion of the covered stent (Figure 1D, arrows). Postdilatation with a non-compliant balloon was performed (3 mm×15 mm; 22 atm), and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) confirmed correct expansion (Figure 1D, 1–4; Video 1). The patient was promptly extubated and discharged. We performed a clinical follow-up, and more than one year later, he remains asymptomatic with no adverse events.

(A) Coronary angiography (right anterior oblique view) showing a severe lesion in the mid left anterior descending artery (arrow); (B) underexpanded biolimus-eluting stent (arrow); (C) coronary artery perforation after postdilation with non-compliant balloon; (D) coronary angiography after hemodynamic stabilization showing probable underexpansion of the covered stent (arrows); (D1–4) intravascular ultrasound after postdilation with non-compliant balloon: (D1) segment with a well-expanded covered stent and hematoma outside the lumen; (D2 and 3) segment with two layers of stent (covered stent and biolimus-eluting stent); (D4) segment with a biolimus-eluting stent only.

CAP is a rare (0.43%)1 but potentially fatal complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. The most reproducible risk factors are oversizing of devices (balloons or stents), female gender, advanced age, atheroablative devices, and treatment of complex lesions.1,2 Morbidity and mortality vary directly with Ellis classification: tamponade and mortality rates range between 0.4% and 0.3% (Ellis class I) to 45.7% and 21.2% (Ellis class III), respectively.1,3

The poor prognosis associated with severe CAP emphasizes the importance of taking measures to prevent this complication. Awareness of risk factors, careful guidewire selection, and avoidance of balloon overexpansion remain the mainstays of CAP prevention.

There is no uniform treatment for CAP. A variety of major management strategies, based on little evidence, have been used, including observation, heparin reversal, platelet transfusion, prolonged balloon inflation, covered stent implantation, distal embolization, pericardiocentesis, and surgery.1 Continuous monitoring is essential since deterioration can occur up to 24–48 hours afterwards. Echocardiography studies should be performed serially.

Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents prevent blood leakage between stent struts, and a high rate of success has been reported. However, they have some limitations: they lack elasticity and rapid and correct deployment in calcified arteries, in which the majority of perforations occur, can be difficult.1 In addition, higher rates of stent restenosis and thrombosis have been described compared with bare-metal stents and drug-eluting stents, and they also have higher rates of adverse events in long-term follow-up.1,2

After stabilizing the patient, we should not rush, because, in cases like ours, intracoronary imaging techniques such as IVUS may be useful to ensure correct expansion and reduce further adverse events.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Pullback of intravascular ultrasound after postdilation of covered stent showing the hematoma outside the lumen and the good final result of the angioplasty, with three segments in the mid left anterior descending artery: a proximal segment with a covered stent (D1), a second segment with two stent layers (covered stent and biolimus-eluting stent) (D2 and 3), and a third segment with a biolimus-eluting stent only (D4).