Respiratory infections usually lead to a physiological response mediated by the autonomic nervous system, which generally includes some degree of tachycardia. Our aim was to investigate the autonomic response in patients with COVID-19 based on the relationship between heart rate (HR), temperature (Tª) and oxygen saturation (SatO2) in the initial assessment at the emergency department. This retrospective, single-center study based on a large cohort of consecutive patients with confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction, was conducted from 1 March to 20 April 2020 in a tertiary hospital in Madrid (Spain).

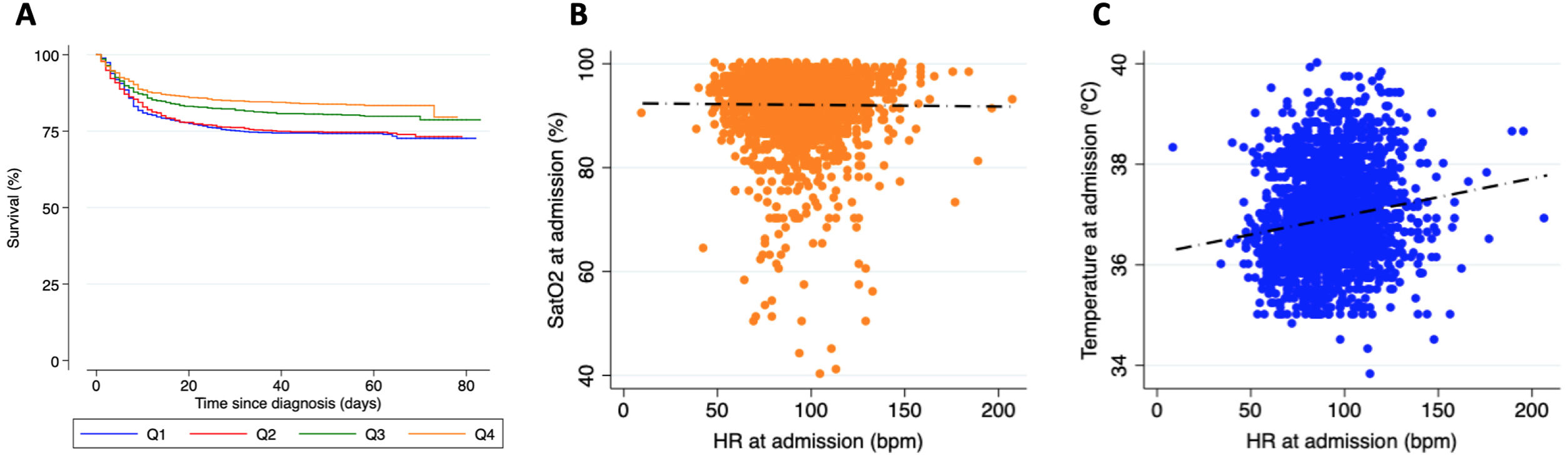

A total of 2757 patients (53.9% male, mean age 64.2±15.6 years) were included in the present analysis (detailed baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1). Among them, 78.1% required hospital admission, with 6.5% requiring admission to critical care units. During a median follow-up of 59 (50-66) days, mortality was 22.3%. Patients in the lowest HR quartiles were older, had more comorbidities and showed higher mortality during follow-up (Figure 1A). Although the proportion of HR lowering drugs was higher in this group, the results were similar in patients who did not take them.

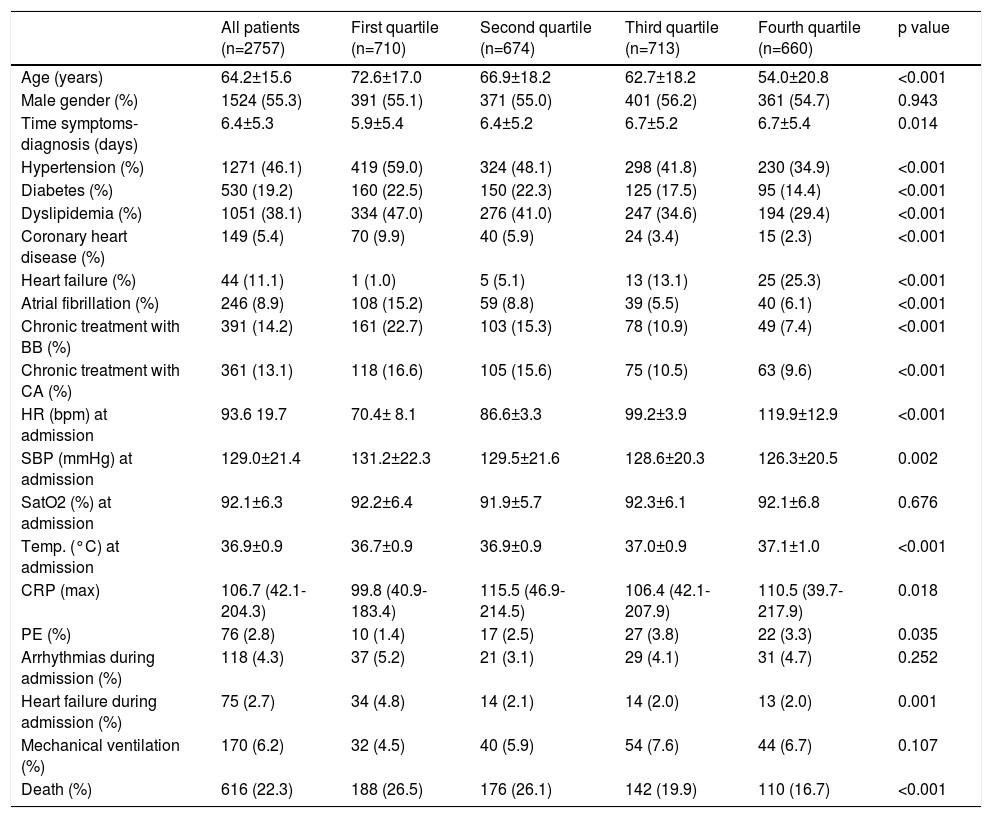

Baseline characteristics and outcomes.

| All patients (n=2757) | First quartile (n=710) | Second quartile (n=674) | Third quartile (n=713) | Fourth quartile (n=660) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.2±15.6 | 72.6±17.0 | 66.9±18.2 | 62.7±18.2 | 54.0±20.8 | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 1524 (55.3) | 391 (55.1) | 371 (55.0) | 401 (56.2) | 361 (54.7) | 0.943 |

| Time symptoms-diagnosis (days) | 6.4±5.3 | 5.9±5.4 | 6.4±5.2 | 6.7±5.2 | 6.7±5.4 | 0.014 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1271 (46.1) | 419 (59.0) | 324 (48.1) | 298 (41.8) | 230 (34.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 530 (19.2) | 160 (22.5) | 150 (22.3) | 125 (17.5) | 95 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 1051 (38.1) | 334 (47.0) | 276 (41.0) | 247 (34.6) | 194 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 149 (5.4) | 70 (9.9) | 40 (5.9) | 24 (3.4) | 15 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 44 (11.1) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (5.1) | 13 (13.1) | 25 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 246 (8.9) | 108 (15.2) | 59 (8.8) | 39 (5.5) | 40 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic treatment with BB (%) | 391 (14.2) | 161 (22.7) | 103 (15.3) | 78 (10.9) | 49 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic treatment with CA (%) | 361 (13.1) | 118 (16.6) | 105 (15.6) | 75 (10.5) | 63 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| HR (bpm) at admission | 93.6 19.7 | 70.4± 8.1 | 86.6±3.3 | 99.2±3.9 | 119.9±12.9 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) at admission | 129.0±21.4 | 131.2±22.3 | 129.5±21.6 | 128.6±20.3 | 126.3±20.5 | 0.002 |

| SatO2 (%) at admission | 92.1±6.3 | 92.2±6.4 | 91.9±5.7 | 92.3±6.1 | 92.1±6.8 | 0.676 |

| Temp. (°C) at admission | 36.9±0.9 | 36.7±0.9 | 36.9±0.9 | 37.0±0.9 | 37.1±1.0 | <0.001 |

| CRP (max) | 106.7 (42.1-204.3) | 99.8 (40.9-183.4) | 115.5 (46.9-214.5) | 106.4 (42.1-207.9) | 110.5 (39.7-217.9) | 0.018 |

| PE (%) | 76 (2.8) | 10 (1.4) | 17 (2.5) | 27 (3.8) | 22 (3.3) | 0.035 |

| Arrhythmias during admission (%) | 118 (4.3) | 37 (5.2) | 21 (3.1) | 29 (4.1) | 31 (4.7) | 0.252 |

| Heart failure during admission (%) | 75 (2.7) | 34 (4.8) | 14 (2.1) | 14 (2.0) | 13 (2.0) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 170 (6.2) | 32 (4.5) | 40 (5.9) | 54 (7.6) | 44 (6.7) | 0.107 |

| Death (%) | 616 (22.3) | 188 (26.5) | 176 (26.1) | 142 (19.9) | 110 (16.7) | <0.001 |

Panel A: Kaplan Meier survival analysis stratified according to the heart rate quartile at hospital admission. Panel B: Scatter plot showing no correlation between SatO2 and heart rate at admission. Panel C: Scatter plot showing a weak correlation between temperature and heart rate at admission.

A more detailed analysis showed that HR did not have a significant correlation with SatO2 at admission (Pearson's correlation coefficient -0.01, p=0.596, Figure 1B), although it did reveal a weak significant correlation with temperature (Pearson's correlation coefficient 0.155, p<0.001, Figure 1C).

Since the beginning of the pandemic, multiple neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been described, ranging from anosmia or dysgeusia to more serious conditions such as Guillain-Barré. However, evidence about its ability to cause dysautonomia is lacking. Although dysautonomia is linked to chronic diseases such as diabetes or Parkinson, cases associated with viral infections (including human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, Epstein-Barr virus or Coxsackie) have also been described. Several studies have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 may affect the nervous system, with a special affinity for the medullary structures and the brainstem. Both areas show a strong expression of angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 and are closely linked to the autonomic nervous system and interoception.1

One of the most surprising aspects of COVID-19 pneumonia is the lack of dyspnea in patients with very low levels of blood oxygen. Some authors use the term “happy hypoxemia” to describe this dissociation. In the Wuhan cohort, only 19% of the patients infected with SARS-CoV2 reported dyspnea; 62% of the patients with severe disease (and approximately half of those who were intubated, ventilated, or died) did not present with dyspnea.2,3 In our setting, the proportion of patients with dyspnea was less than 50%.4

Besides, also in favor of COVID-19-associated dysautonomia, cases of relative bradycardia (inappropriately low HR in response to an increase in temperature) have been described, however the pathophysiology is not entirely clear. Among the postulated mechanisms are the increase in vagal tone, a direct effect on the myocardium and sinoatrial node or mediated by the cytokine cascade. Some authors even postulate that the presence of sinus bradycardia may be a red flag that precedes the clinical worsening of the patient.5,6 The absence of the development of proportionate tachycardia based on SatO2 at admission supports the existence of a certain degree of dysautonomia. This could partly explain the good clinical tolerance to hypoxia in the initial stages of the disease. However, worse outcomes in patients with lower HRs may reflect major autonomic involvement in patients with severe disease and may be associated with worse prognosis.

Although more studies are needed, dysautonomia must not delay appropriate management of COVID-19 patients (in the case of hypoxia-dyspnea dissociation). In fact, it may signal clinical worsening.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.