From ancient times salicylate-containing plants, such as the willow, have been commonly used to relieve pain and fever. In the 20th century, scientists discovered the details of aspirin's anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, including its molecular mechanism of action. In addition, in the latter half of the century, the use of daily low-dose aspirin was associated with the prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke.1,2 Aspirin is now widely used in human medicine and has effectively become a household drug, mainly due to its widespread use as an analgesic and general anti-inflammatory agent.

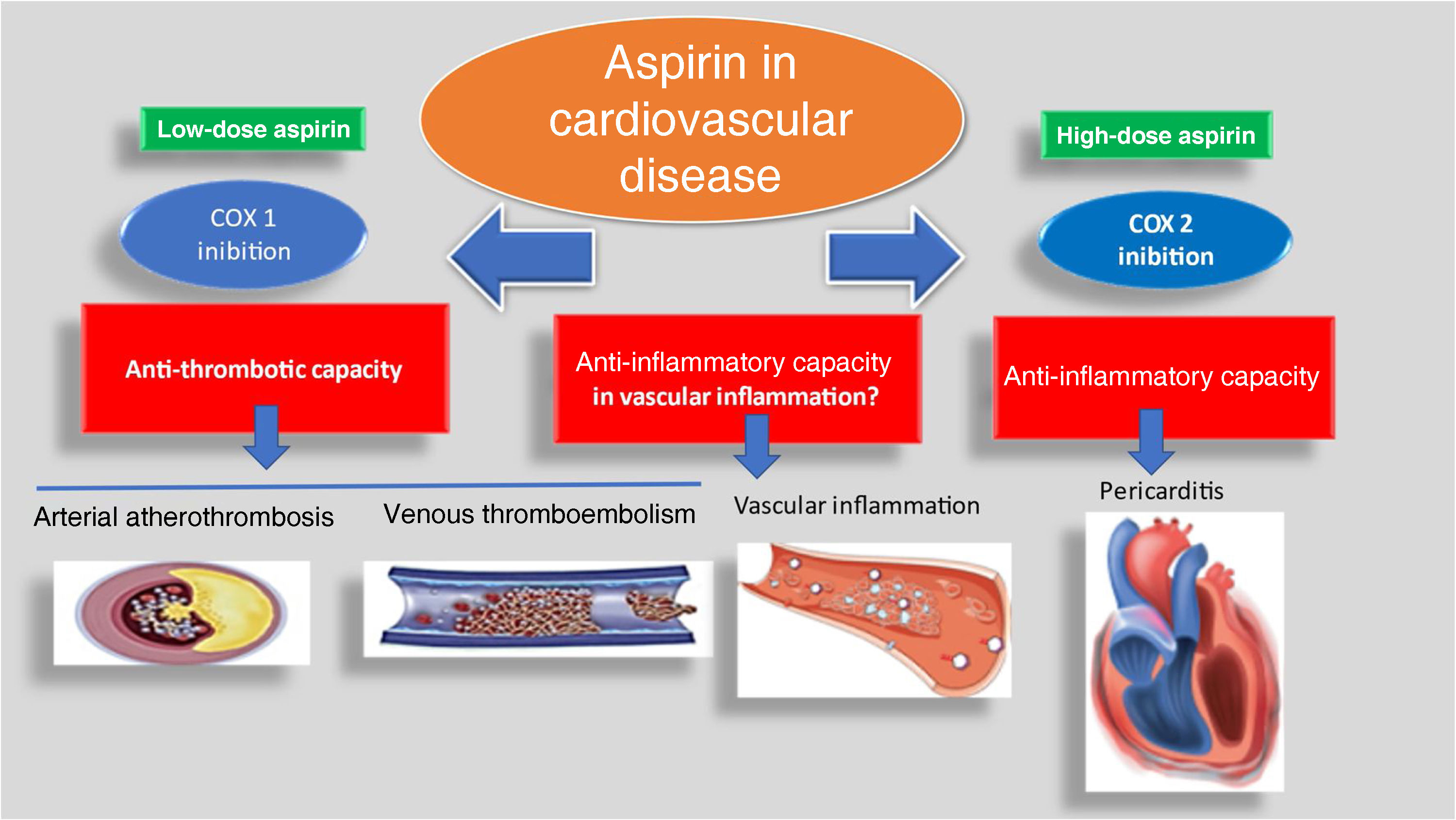

The main capabilities of aspirin in cardiovascular disease are depicted in Figure 1 and are widely accepted.3 Some authors still associate aspirin with capabilities in other areas, like the prevention of colon cancer or the prevention of dementia.3,4 These connections are still unproven.4 There was also a relatively recent suggestion that low-dose aspirin can curb vascular inflammation, the biological genesis of atherosclerosis.5 This assumption is also hotly debated.6

The spectrum of aspirin use in cardiovascular disease over the years. Low-dose aspirin (a COX 1 inhibitor) has been widely used in the prevention of arterial atherothrombosis and sometimes as an adjunctive agent in venous thromboembolism; it has also been proposed as possibly able to curb vascular inflammation. At higher dosages, it is still used in pericarditis.

It is clear that the side effects (especially gastrointestinal bleeding) of this widely used agent have not deterred patients and health authorities everywhere from over-the-counter sales of the drug. As a result, low-dose aspirin has become the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention in cardiovascular medicine.7,8 Its mechanisms (and the ways in which they fail) have been extensively studied.9

Some of the readers of the study by Moita et al.10 in this issue of the Journal might find the analysis presented awkward. In fact, the guidelines on both sides of the Atlantic have changed and aspirin in primary prevention is now reserved for high-risk patients (sometimes a difficult assessment). However, low-dose aspirin remains the cornerstone for secondary prevention.11,12 This change of attitude has occurred, as the authors rightly point out, due to the risk of gastric bleeding associated with chronic aspirin use.

Moita et al.’s work is important, firstly because the prevalence of aspirin use in primary prevention in the Portuguese general practice setting under study was still relatively high, albeit mostly associated with high or very high cardiovascular risk (>50% of patients). However, hypertension was the most prevalent risk factor. This raises an important issue, since the relationship between hypertension and aspirin is still problematic, mainly due to vasomotor changes induced by chronic aspirin use and in the interaction between aspirin and some antihypertensive drugs.13 The risk of cerebrovascular bleeding in uncontrolled hypertensive patients (a common occurrence in this common condition) is also higher, so aspirin should not be used in hypertensive patients unless previously established cardiovascular disease is present.14

This paper is also important because it depicts the idiosyncrasy of Portuguese medical practice concerning the dosages used, in both primary and secondary prevention. In fact, the lowest possible dosage should be used, ‘low-dose’ being universally defined as between 75 and 100 mg/day.11,12 For reasons related to the Portuguese medical reimbursement system, as Moita et al. explain, the 150 mg dose is predominant in both primary and secondary prevention, because it is cheaper. Unfortunately, to my knowledge, there has been no study in Portugal comparing the use of lower dosages (<150 mg daily) versus 150 mg in terms of the risk of gastric bleeding. Nevertheless, higher doses would be expected to entail a higher gastrointestinal bleeding risk. This is clearly an important point that merits the attention of the country's health authorities, as the authors duly point out.

Generally, I believe this information to be crucial in alerting us to important problems currently facing physicians regarding the use of aspirin. Firstly, it is common knowledge among patients themselves that aspirin is important in preventive cardiovascular medicine, so those already taking aspirin for primary prevention (sometimes for years) may find it strange if they are told not to take it (even if they have gastric lesions induced by chronic aspirin use, or are forced to take a proton pump inhibitor). On the other hand, many patients do not adhere to aspirin prescription in secondary prevention, as Moita et al.’s study demonstrates. Non-adherence to treatment is a real problem in many chronic non-transmissible conditions, and is also related to physicians’ own therapeutic inertia.15

In conclusion, this work should make us rethink our practice, in order to ensure careful selection of patients to be placed in primary prevention. This selection should include a detailed analysis of their cardiovascular risk, especially in older people in whom the bleeding risk is higher.11,16 We should also have the courage to discontinue aspirin in doubtful cases.

The myth of ‘aspirin for all’ in cardiovascular medicine is gone. The current paradigm requires active doctors and informed patients. This is, I believe, the underlying message of the present study, for which the authors are to be congratulated. Aspirin will still be an important and cheap drug all over the world, especially in very low-income countries, where it is still a valuable antipyretic and anti-inflammatory agent. In some of these countries, in which I have had the honor of working, one is truly happy to have this universal drug. Thus, many believe this ‘all-terrain’ pharmaceutical wonder will still be around for a long while. I am glad it will be so.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.