Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most prevalent valvular heart disease in developed countries. Diagnosis, risk stratification and monitoring are usually based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters. Complementary methods are needed to improve management and outcome, particularly in patients with severe asymptomatic AS, whose management remains controversial. Natriuretic peptides (NPs) have established value as biomarkers in heart failure, coronary heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. This review discusses the usefulness and prognostic value of natriuretic peptides in AS. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and its prohormone (NT-proBNP) correlate with disease severity, development of symptoms and prognosis, but before they can be routinely used in clinical practice, additional prospective studies are needed.

A estenose aórtica (EA) é a doença valvular mais prevalente em países desenvolvidos. O diagnóstico, a estratificação do risco e a monitorização são habitualmente baseados em parâmetros clínicos e ecocardiográficos. São necessários métodos complementares para melhorar a gestão e os resultados, particularmente nos doentes com EA grave assintomática, cuja abordagem permanece controversa. Os peptídeos natriuréticos (PN) demonstraram utilidade como biomarcadores na insuficiência cardíaca, cardiopatia isquémica e hipertensão pulmonar. Esta revisão pretende discutir a utilidade e valor prognóstico dos PN na AS. O Peptídeo natriurético do tipo B (BNP) e a sua prohormona (NT-proBNP) correlacionam-se com a gravidade da doença, desenvolvimento de sintomas e prognóstico, mas antes do seu uso por rotina na prática clínica, são necessários estudos prospetivos adicionais.

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common of all valvular heart diseases in the developed world and its prevalence may double in the next 20 years as populations age.1 The management of AS usually involves monitoring for clinical symptoms and functional deterioration generally assessed by transthoracic echocardiography. The current treatment of choice in symptomatic AS is aortic valve replacement (AVR), but the optimal timing for surgery in asymptomatic patients remains controversial.2–4 A watchful waiting strategy is both safe and viable, but the risk of sudden death is not negligible, reaching almost 5% per year,5 and the association between symptom status and AS severity may not always be linear.

Biomarkers are defined as biological molecules that can be identified in a particular disease and can additionally assess the severity and prognosis or monitor the response to treatment of that disease state.6 In valvular disease, a strong biomarker will be very useful, potentially avoiding the need for costly imaging studies and providing support to clinical management decisions, particularly the optimal timing for intervention in asymptomatic AS. Natriuretic peptides (NPs) are endogenous cardiac hormones that have shown utility as biomarkers in heart failure,7,8 ischemic heart disease9,10 and pulmonary hypertension.11 This review examines the role of NPs as potential biomarkers in the management of AS, with particular emphasis on asymptomatic severe AS.

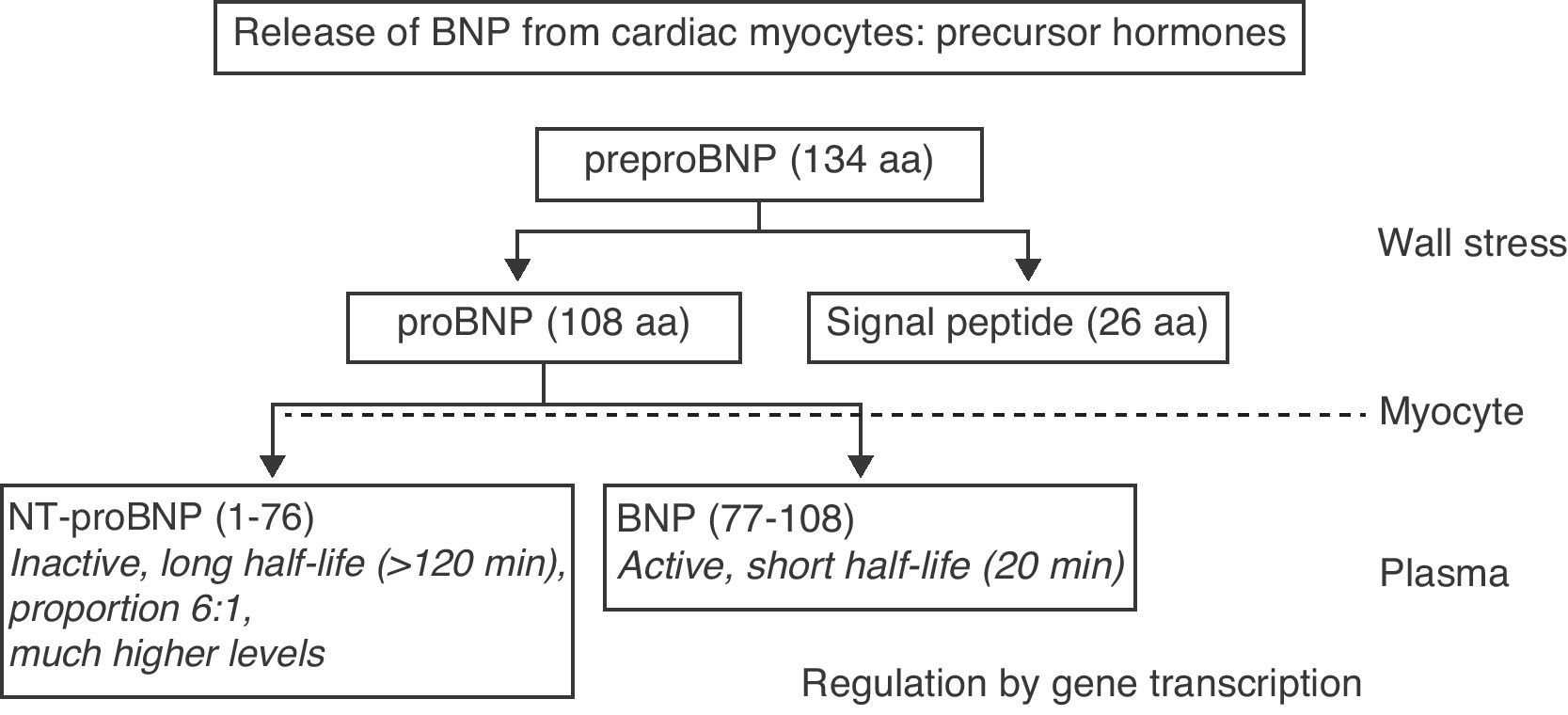

Natriuretic peptidesThe NP system consists of three main peptides: atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP). Their complex physiology will not be discussed here in detail as it has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.12,13 BNP and ANP exist as prohormones that are cleaved into inactive N-terminal fragments (N-terminal proBNP [NT-proBNP], N-terminal proANP [NT-proANP]) and biologically active hormones (BNP, ANP) before release into the circulation (Figure 1). The N-terminal fragments are more stable in vivo and are often used as surrogate markers for the biologically active hormone. The predominant cardiac source of ANP is the atria, while the ventricles are the main cardiac source of BNP, although both can be synthesized in either chamber. The stimulus for ANP and BNP release is primarily myocyte stretch, but endothelin-I, nitric oxide, and angiotensin II may all have a role. ANP concentrations are more closely related to left atrial (LA) pressure and BNP to left ventricular (LV) pressure. CNP is structurally distinct from ANP and BNP; it is expressed to a much greater extent in the central nervous system and vascular tissues than in the heart, acting as a potent vasorelaxant and inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle proliferation and endothelial cell migration. Three natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) have been identified: NPR-A and NPR-B, which mediate their biological action, and NPR-C, which is a clearance receptor. NPs’ cardiovascular and renal actions include natriuresis, increase in glomerular filtration, systemic vasodilation, inhibition of renin release, reduction of left ventricular remodeling, and reduction of venous and wedge pressures. Additionally, NPs, their processing enzymes, and their receptors are expressed in the cardiac valves themselves.14

Release of BNP into the circulation from cardiac myocytes via precursor hormones. aa: amino acids.

On the basis of currently available evidence, the need for better risk stratification of asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe AS is widely accepted, and biomarkers may play an important role here. The ideal biomarker should be easily and reliably measured, reflect disease severity, increase with disease progression, and discriminate between patients in whom symptoms will or will not develop in the short to medium term. In comparison with controls, AS has been strongly associated with increased NP levels.16,17 In AS, pressure overload induces significant expression of BNP and NT-proBNP.18,19 ANP levels have also been demonstrated to be raised in proportion to LV end-systolic wall stress in patients with AS.20

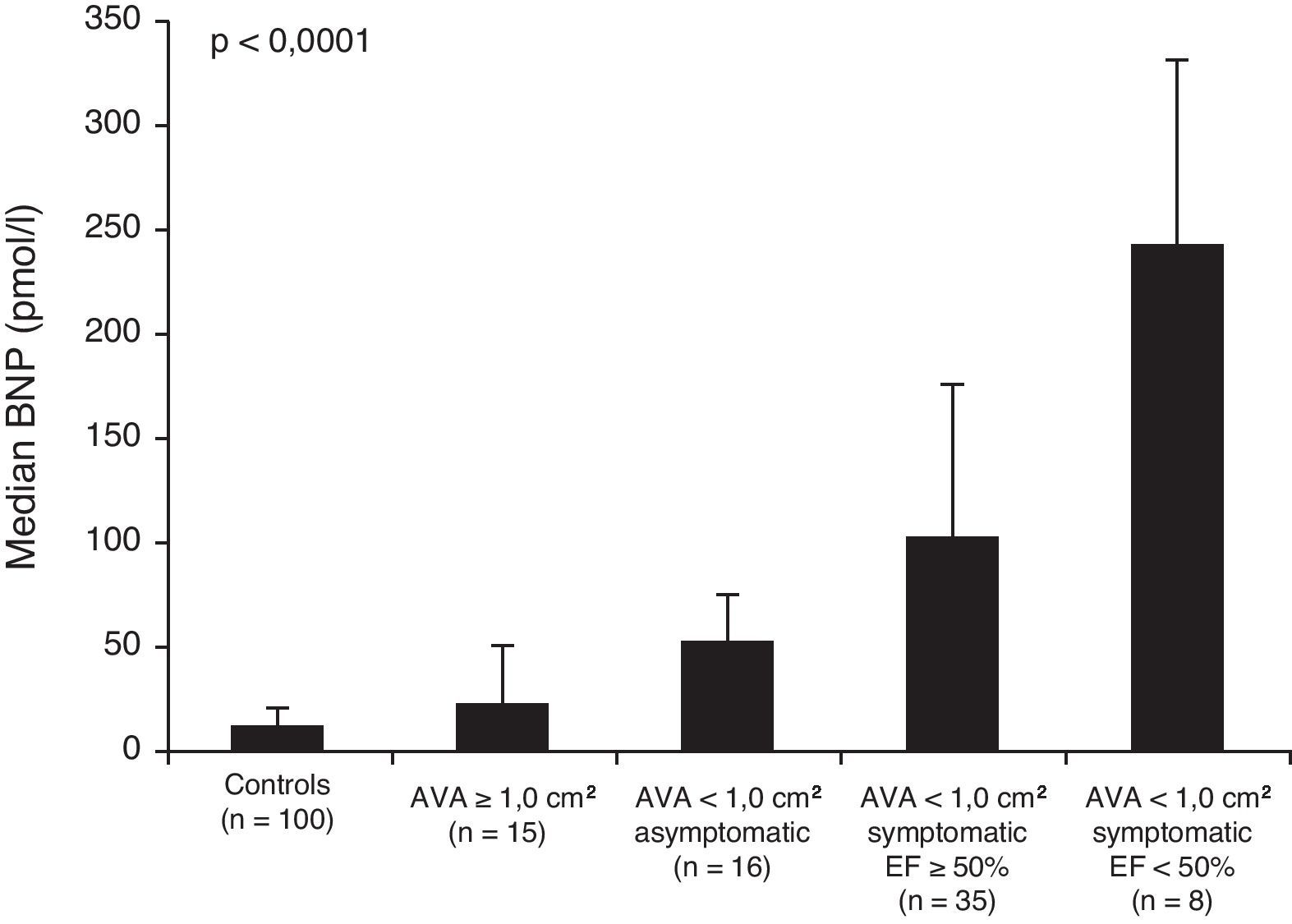

Severity of aortic stenosisSeveral studies have shown a correlation between plasma NP levels and severity of AS.16,21–24 This is the case for both BNP and NT-proBNP. Although there is a correlation between transvalvular gradients and NT-proBNP levels,24 more recent data suggest that the best correlation between NP levels and severity of AS is observed when aortic valve area is used as a categorical variable (Figure 2). 23,25,26 Although a good overall correlation with aortic parameters of severity is observed, NPs should not be considered a replacement for an expert baseline echocardiographic evaluation of the patient, but as additional and important prognostic information.

Association between BNP levels and severity of aortic stenosis, showing BNP levels (median [upper quartile]) in normal controls and in subgroups of patients with aortic stenosis by aortic valve area, symptoms, and LV systolic function. AVA: aortic valve area; EF: ejection fraction.

NPs are higher in symptomatic than in asymptomatic patients with AS. NT-proBNP and BNP increases significantly with AS severity, onset of symptoms and LV dysfunction. In symptomatic patients, NPs increase with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, irrespective of the severity of AS.17,21,23,27 BNP has good diagnostic accuracy in patients in NYHA functional class III to IV (area under the receiver-operator curve 0.78 [95% CI: 0.66 to 0.87; best cutoff 254.64 pg/ml]).27 Its ability to differentiate asymptomatic from minimally symptomatic (i.e., NYHA functional classes I and II) patients is weaker, with studies showing contradictory results.22,23 Angina and syncope do not seem to be related to natriuretic peptides,22,25,27 possibly reflecting differences in the pathophysiology of these symptoms compared with dyspnea. Therefore, high NPs in a possibly asymptomatic patient or in a symptomatic patient with unclear symptoms appears to point to underlying progression of the disease, and these patients should be monitored closely.

Outcome in severe unoperated aortic stenosisThe timing for identifying symptom development in asymptomatic AS is crucial in the progression of the disease and has important prognostic impact. There is evidence that asymptomatic patients with severe AS and high NP levels developed symptoms earlier and significantly more often than patients with lower levels.23,28 Baseline plasma NP levels are higher in patients developing symptoms and needing surgery compared with asymptomatic patients during follow-up.23 Aortic valve area, peak aortic velocity and LV ejection fraction were less reliable predictors of symptom onset.28 Different NP cutoff levels have been proposed in diverse studies on AS regarding the optimal timing for surgery. However, single-value reference cutoffs as in heart failure12 may not be appropriate; it might be preferable to assess individual baseline NPs levels and monitor for a possible increase during 3- to 6-month follow-up.15

Elevated plasma NPs has been shown to predict survival in patients with severe AS. In Nessmith et al.’s study,29 in elderly patients with moderate to severe AS, survival was significantly influenced by the presence of symptoms (relative risk: 7.5, p<0.01) and BNP tertile (relative risk: 2.9, p<0.001). One-year mortality without surgery was 6%, 34%, and 60% with increasing tertiles. No patients with BNP <100 pg/ml died in the first year and the combination of BNP and symptoms provided a better prediction of survival than symptoms alone.29 Patients with AS and death due to congestive heart failure or adverse events due to cardiac decompensation have consistently higher BNP levels.22,23,27,30 Less data are available for NPs and sudden death, especially in asymptomatic AS. The risk of sudden death, although it may be low overall, must be considered in patients with severe asymptomatic AS.31,32 Low BNP may not be able to preclude the risk of sudden death in AS; it has been observed that AS patients with sudden death also had relatively low levels of BNP or NT-proBNP.23,25

Postoperative outcome following aortic valve replacementImmediately after surgical AVR, NPs rise33,34 and then after 6 and 12 months post-AVR, decrease significantly, reflecting substantial hemodynamic improvement, but without returning to normal levels.21,35 These decreases occur in parallel with decreases in mean transvalvular pressure gradient and left ventricular mass.26 Post-AVR changes in LA volume and LA pressure are reflected in ANP36 and NT-proANP37 levels, respectively. Persistently elevated BNP levels postoperatively appear to point to poor overall outcome late after aortic valve replacement. BNP may remain elevated in aortic prosthesis mismatch due to residual aortic gradient and increased LV myocardial wall pressure, leading to the poor outcomes observed in these patients. Weber et al.26 showed a significant decrease in NT-proBNP as a function of type and size of aortic prosthesis. Patients with bioprostheses had higher postoperative NT-proBNP levels compared to mechanical prostheses, although this was age-related. Smaller prosthesis size was associated with higher transvalvular gradients and a tendency toward higher NT-proBNP levels.

Patients without symptomatic improvement tend to have nonsignificant decreases in NT-proBNP and LV mass even though the transvalvular pressure gradient decreases.26 Several studies have evaluated the prognostic impact of NPs on survival in operated patients with severe AS. Pedrazzini et al.30 observed that BNP level was an independent predictor of perioperative and long-term mortality and was superior to the commonly used logistic EuroSCORE. Patients with logistic EuroSCORE greater than 10.1% had a higher risk of dying over time (hazard ratio [HR] 2.86; p=0.037), as had patients with BNP greater than 312 pg/ml (HR 9.01; p<0.001). However, only BNP was an independent predictor of death (HR 8.2; p=0.002). Importantly, BNP should not be considered as a stand-alone parameter to decide for or against AVR. The prognostic role of NPs is improved if combined with clinical findings, comorbidities and surgical risk scores such as EuroSCORE.

Exercise testing in asymptomatic aortic stenosisPatients with asymptomatic AS and abnormal hemodynamic responses to exercise testing are at increased risk for cardiac events. In asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic AS, higher plasma BNP levels are a better predictor of an abnormal blood pressure response to exercise than echocardiographic measures of aortic valve severity.38 In moderate to severe asymptomatic AS, BNP was associated with lower peak systolic velocity of the mitral valve annulus on exercise and reduced exercise capacity compared with controls.39 Thus, in asymptomatic AS elevated BNP seems to reflect reduced myocardial functional reserve and is therefore indicative of LV dysfunction with exercise despite normal measures of systolic function at rest. Newer approaches, such as longitudinal LV strain by speckle tracking or tissue Doppler methods, may also reflect early worsening of LV function and have been shown to be related to BNP levels.36,40

Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosisPatients with severe AS and low cardiac output often present with a relatively low transvalvular pressure gradient (mean gradient less than 30mmHg). Such patients can be difficult to distinguish from those with low cardiac output and only mild to moderate AS. In the former (true anatomically severe AS), the stenotic lesion contributes to elevated afterload, decreased ejection fraction, and low stroke volume. In the latter, primary contractile dysfunction is responsible for the decreased ejection fraction and low stroke volume. Dobutamine stress echocardiography is valuable in determining the actual severity of aortic valve stenosis and evaluating LV contractile reserve. Patients with LV dysfunction and low-flow, low-gradient AS, who account for 5%-10% of AS patients, represent the most challenging and controversial subset of patients to manage. These patients generally have a poor prognosis with conservative therapy, but high operative mortality if treated surgically. In the TOPAS (Truly or Pseudo-Severe Aortic Stenosis) study, BNP was higher in patients with truly severe compared with pseudo-severe AS and correlated with AS severity and LV ejection fraction.41 This may be caused by the more extensive LV afterload in patients with more severe AS. However, a large overlap of BNP levels was observed, and therefore BNP does not appear useful for determining the true severity of stenosis in the individual patient. The most important finding of this study was the relationship between BNP and survival in low-flow, low-gradient AS. With BNP levels ≥550 pg/ml, the cumulative 1-year survival of the total cohort compared with those with BNP levels <550 pg/ml was 47±9% vs. 97±3% (p<0.0001), and postoperative survival was 53±13% vs. 92±7%. Furthermore, high BNP levels predicted poor outcome independently of contractile reserve, defined by increase in stroke volume greater than 20% on dobutamine stress echocardiography.41

BNP levels, combined with clinical and echocardiographic parameters, may improve risk stratification in low-flow, low-gradient AS. Due to their high operative risk, these patients might be candidates for new surgical or catheter interventions, such as percutaneous aortic valve replacement or transapical valve implantation.42

Transcatheter aortic valve implantationTranscatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a relatively recent technique developed to provide an alternative therapeutic solution for severe symptomatic AS patients at prohibitive or high surgical risk who are not candidates for AVR.43,44 The indications for TAVI remain controversial. Despite the minimally invasive nature of the technique, significant clinical benefit and quality of life improvement,45 post-procedural complications and mortality remain high.46,47 Appropriate evaluation and risk stratification is needed to identify patients who would not succumb to comorbidities after TAVI. Present data suggests that NPs could be helpful in improving patient selection. Kefer et al.48 found that, in a TAVI population, a baseline BNP level >428 pg/ml was helpful for discriminating survival at 30 days. BNP levels (baseline and 24hours after TAVI) were independent predictors of 30-day survival. Optimization of patients with evidence of high neurohormonal activation, by adjusting medical therapy or using percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty,49 could be considered as a bridge therapy, to enable use of TAVI in stable hemodynamic conditions and hence to reduce periprocedural risk.

ConclusionsAfter examining the evidence concerning neurohormonal assessment of AS, some further points need to be taken into consideration. Several conditions may result in increased NP levels,12 including coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, mitral regurgitation, severe respiratory disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and renal failure. These need to be considered when measuring NP levels in clinical practice in AS patients. Additionally, plasma NP levels increase with age and are higher in women than men after adjustment for age.

In AS, plasma NP levels are higher in symptomatic than in asymptomatic patients after adjustment for echocardiographic measures of aortic stenosis severity and LV function and increase with increasing severity of dyspnea and fatigue, but are not associated with angina or syncope. Measurement of plasma NP levels is likely to complement clinical and echocardiographic evaluation of AS patients for predicting outcome and stratifying risk. NPs appear to be helpful in evaluating asymptomatic AS and defining optimal timing for AVR, and also in selecting high surgical risk severe AS patients who are candidates for TAVI. However, prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm its value so that they can be integrated in routine clinical practice.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

![Association between BNP levels and severity of aortic stenosis, showing BNP levels (median [upper quartile]) in normal controls and in subgroups of patients with aortic stenosis by aortic valve area, symptoms, and LV systolic function. AVA: aortic valve area; EF: ejection fraction. Association between BNP levels and severity of aortic stenosis, showing BNP levels (median [upper quartile]) in normal controls and in subgroups of patients with aortic stenosis by aortic valve area, symptoms, and LV systolic function. AVA: aortic valve area; EF: ejection fraction.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/08702551/0000003100000010/v1_201308021325/S0870255112001746/v1_201308021325/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w9znTMwFdb/TnkS0koegILxs=)