Pericarditis is an inflammation of the pericardium. It may be infectious or secondary to a systemic disease. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical findings, course, treatment and follow-up of children diagnosed with pericarditis at our center.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective analysis of all children admitted to our pediatric cardiology unit with pericarditis between 2003 and 2015. Patient characteristics were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with percentiles for continuous variables.

ResultsFifty patients were analyzed (40 male, 10 female) with a median age of 14 years. The most common diagnosis was acute pericarditis (80%). Thirty-five patients (70%) presented with chest pain and 26% reported fever. Cardiomegaly was identified on chest X-ray in 11 patients (22%), 30 patients (60%) had an abnormal ECG and 44 patients (80%) had alterations on the transthoracic echocardiogram. In 17 cases (34%) there was myocardial involvement. Forty-eight percent of patients presented with infectious pericarditis and the pathologic agent was identified in half of them. Postpericardiotomy syndrome was diagnosed in five cases. The first-line therapy was aspirin in 50% of cases. Pericardiocentesis was performed in 12 patients. The median length of stay was nine days. There was symptom recurrence in seven children.

ConclusionsIn this study, acute infectious pericarditis was the most common presentation and about one third of patients also had myocarditis. The symptom recurrence rate was not negligible and is probably related to the type of therapy employed.

A pericardite é uma doença inflamatória que ocorre de forma isolada ou em contexto de doença sistémica. Neste trabalho pretende-se caracterizar a forma de apresentação, orientação diagnóstica e terapêutica, e o seguimento dos doentes internados com este diagnóstico.

MétodosAnálise descritiva retrospetiva de doentes internados num único Serviço de Cardiologia Pediátrica, com o diagnóstico de pericardite, entre 2003 e 2015. As características da população são expressas em frequência e percentagem nas variáveis categóricas e em mediana e percentis nas variáveis contínuas.

ResultadosIdentificaram-se cinquenta doentes, sendo predominante o sexo masculino (80%) e com uma mediana de idades de 14 anos. A pericardite aguda foi o diagnóstico mais frequente (80%). Na avaliação inicial, 35 doentes (70%) apresentaram toracalgia e 13 (26%) relataram febre. Em 11 doentes (22%) verificou-se cardiomegália na radiografia do tórax, em 30 (60%) registaram-se alterações do ECG e em 44 (88%) observaram-se alterações no ecocardiograma transtorácico. Em 17 casos (34%) foi diagnosticada miopericardite. A etiologia mais comum foi a infeciosa (48%), com agente identificado em metade dos casos. Houve cinco casos de Síndrome Pós-Pericardiotomia. A primeira linha terapêutica foi o ácido acetilsalicílico (50%). Em 12 doentes (24%) realizou-se pericardiocentese. A duração do internamento teve uma mediana de nove dias. Em sete crianças (14%) houve recorrência dos sintomas após o episódio inaugural.

ConclusõesNesta casuística verificou-se que a causa mais frequente de pericardite foi a infeciosa. Em um terço dos doentes decorreu com componente de miocardite e a recidiva não é desprezível com a terapêutica clássica.

The pericardium is composed of a double membrane surrounding the heart and the roots of the great vessels. Its functions include fixing the heart in the mediastinum and protecting it from infection.1,2 Pericarditis is an inflammatory process involving the pericardium that may include pericardial effusion. It is uncommon at pediatric ages, accounting for around 5% of cases of chest pain seen in emergency departments.1,3 Some episodes are self-limiting, and consequently the true incidence is unknown. A high index of suspicion is therefore necessary for a diagnosis of pericarditis in children, since symptoms may also be non-specific.4

The aim of this study was to characterize the population of children referred to a pediatric cardiology unit and admitted with a diagnosis of pericarditis.

MethodsThis observational study presents a retrospective analysis of data on all children admitted between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2015 to the pediatric cardiology unit of a tertiary hospital with pericarditis diagnosed according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Data on demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, diagnostic exams, treatment and follow-up were obtained from patients’ medical records and underwent descriptive analysis. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages and continuous variables were expressed as medians with percentiles.

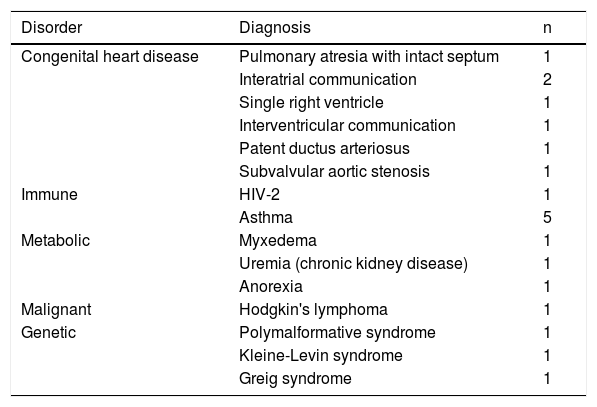

ResultsFifty patients were admitted during the study period, nine as outpatients, 14 through the pediatric emergency department in our hospital, and the remainder transferred from other hospitals in our center's referral area. Forty patients (80%) were male and 10 (20%) were female. Median age was 14 years (interquartile range 9-15 years). Relevant personal history included congenital heart disease, found in seven (14%) cases, immune disorders in six (12%) cases, metabolic and genetic disorders (6% each), and one patient with malignant disease (Table 1).

Personal history of patients in the study population.

| Disorder | Diagnosis | n |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital heart disease | Pulmonary atresia with intact septum | 1 |

| Interatrial communication | 2 | |

| Single right ventricle | 1 | |

| Interventricular communication | 1 | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 1 | |

| Subvalvular aortic stenosis | 1 | |

| Immune | HIV-2 | 1 |

| Asthma | 5 | |

| Metabolic | Myxedema | 1 |

| Uremia (chronic kidney disease) | 1 | |

| Anorexia | 1 | |

| Malignant | Hodgkin's lymphoma | 1 |

| Genetic | Polymalformative syndrome | 1 |

| Kleine-Levin syndrome | 1 | |

| Greig syndrome | 1 |

The most frequent form of presentation was chest pain, in 35 patients (75%), followed by fever in 13 cases (26%), fatigue in nine (18%), and dyspnea in six (12%). There were some reports of prostration and gastrointestinal symptoms, including refusal to eat and vomiting.

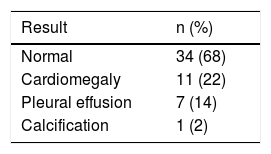

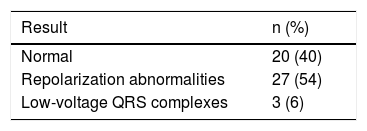

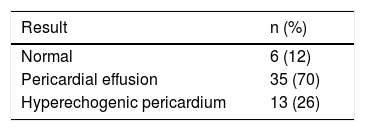

The results of diagnostic exams performed are presented in Tables 2-4.

On laboratory testing, elevated inflammatory/infection markers were seen in 36 patients (72%) and in 17 cases (35%) markers of myocardial damage (troponin I and CK) were elevated, indicating myocardial involvement in the disease process.

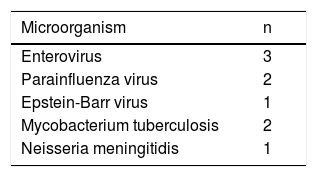

The etiological investigation identified an infectious cause in 24 cases (48%) following a detailed personal history revealing recent respiratory or gastrointestinal infection and identification by laboratory tests of the organism responsible (Table 5). A non-infectious etiology was found in eight patients (16%), of whom five were diagnosed with postpericardiotomy syndrome, two had underlying metabolic disorders and in one the cause was attributed to malignancy. The disease was considered idiopathic in 18 patients (36%).

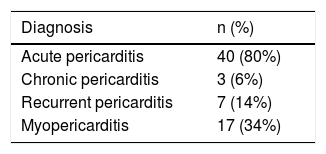

With regard to complications, eight patients (16%) presented cardiac tamponade, four (8%) developed pericardial constriction and in seven cases (14%) symptoms recurred after the initial episode.

Medical therapy was based on anti-inflammatory drugs, mainly aspirin in 25 cases (50%) and ibuprofen in 21 cases (42%). Corticosteroid therapy was used in selected cases (four patients) and colchicine in two.

Surgery was required in 14 patients (28%), in 12 of whom pericardiocentesis was performed and pericardiectomy in two.

Most patients (40, 80%) were diagnosed with acute pericarditis on the basis of an overall assessment. Definitive diagnoses established over long-term follow-up are listed in Table 6.

DiscussionPericarditis may be caused by infection, and the most common etiology at pediatric ages is viral.1 In our study, 42% of the children were diagnosed with viral pericarditis and the infectious agent was identified in more than a quarter of cases. Bacterial etiology is less frequent.1 There were two cases of tuberculous pericarditis in our series, one of which occurred in the context of secondary immunodeficiency [in pdf, line 141, change hyphenation from immunod-eficiency to immuno-deficiency] due to HIV-2 infection. Tuberculous pericarditis is strongly associated with HIV infection, particularly in developing countries, while constrictive forms are less common in immunodeficient patients.5 Although there was pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis in both of these cases, neither developed constrictive pericarditis.

In 36% of the cases no cause could be identified, a similar figure to that in the review by Shakti et al.,6 in which 37-68% of cases were considered idiopathic.

In our series, the most common etiology during adolescence was viral or idiopathic, particularly in males. These are also the most frequent causes reported by other authors.6,7

Pericarditis may also occur in non-infectious contexts, such as an underlying systemic disease2 or cardiac surgery in patients with heart disease.6,8 Of the seven patients in our series with congenital heart disease, five were diagnosed with postpericardiotomy syndrome following surgery. This syndrome is more common in children than in adults, particularly in cases of atrial septal defect closure,8,9 as seen in two of our patients. Recurrence is also more likely in these situations,8,10 but in our study population only one patient developed chronic pericarditis.

When the myocardium is involved in the inflammatory process underlying pericarditis, the result is myopericarditis. The two entities have etiological agents in common, particularly cardiotropic viruses such as enterovirus.1,11 Myopericarditis is identified by the same clinical criteria as pericarditis together with elevated markers of myocardial damage such as troponin I.1,12 The incidence of myopericarditis in our series was 34%, higher than in Imazio et al.,13 who reported an incidence of 10-15%, which may be due to our use of high-sensitivity troponin I assays, or to referral bias seen in our tertiary pediatric cardiology center.

The rate of complications was not negligible; 30% of the children developed some kind of unfavorable outcome. Most cases of recurrence were associated with idiopathic pericarditis. The incidence of complications varies according to etiology, and certain clinical parameters are predictors of worse outcome, including temperature over 38 °C, subacute onset, cardiac tamponade, and lack of response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) after a week.14

The therapeutic approach is based on the underlying cause. In cases of uncomplicated viral or idiopathic etiology, treatment is symptomatic, consisting primarily of the administration of NSAIDs.1 During the study period of our series, aspirin and ibuprofen were prescribed in similar proportions as first-line therapy. Of the cases in which systemic corticosteroid therapy was used, two were for acute pericarditis and two were for recurrent disease. Colchicine was used in one case of recurrent pericarditis and one chronic case, without significant effect. There is evidence that colchicine, when used as adjuvant therapy to NSAIDs, reduces short-term persistence of symptoms and risk of recurrence in patients with acute or recurrent disease.15 The latest guidelines on pericardial disease1 recommend ibuprofen rather than aspirin as first-line therapy in children and colchicine as adjuvant in refractory or recurrent disease.1,2 Despite these recommendations, inconsistency in the results of colchicine use demonstrates the need for randomized controlled trials.16 Corticosteroid therapy should be avoided in children due to side effects, particularly growth impairment, and should be limited to cases associated with autoimmune disease.1 A new therapeutic option is anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, which has shown efficacy in cases of recurrent pericarditis and corticosteroid dependency.1,17

In cases complicated by cardiac tamponade or pericardial constriction, surgery is required to relieve symptoms. Tamponade generally resolves following pericardiocentesis, while pericardiectomy is recommended as the only definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis.18

ConclusionsPericarditis is an uncommon entity in children and few studies have been published on the condition in pediatric ages. A high index of suspicion is therefore needed for the diagnosis.

Assessment of the degree of myocardial involvement and of persistence of lesions is important for determining prognosis in cases of myopericarditis.

The advent of new therapeutic options may have a significant impact on recurrence of episodes.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Perez-Brandão C, Trigo C, Pinto FF. Pericardite – apresentação e características numa população pediátrica. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:97–101.