The use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia has significantly altered the prognosis of this disease, enabling close to normal life expectancy.

Despite their undeniable benefits, the use of TKIs is associated with an increased risk of side effects on the cardiovascular system, particularly of atherothrombotic events. It is therefore necessary to understand and prevent the adverse effects of these drugs, in order to enable antileukemic therapy to continue and to minimize patients’ toxic exposure.

This multidisciplinary consensus document, developed through a collaboration between hematologists and cardiologists, aims to review the cardiovascular toxicity associated with various TKIs and to establish recommendations for the follow-up of these patients. Measures are also proposed for the assessment and reduction of cardiovascular risk in these patients and referral criteria, and relevant drug interactions are discussed.

O uso dos inibidores da tirosina cínase (ITC) para o tratamento da leucemia mieloide crónica alterou significativamente o prognóstico dessa doença e permitiu uma esperança de vida praticamente normal. Apesar dos seus inegáveis benefícios, o uso dos ITC está associado a um aumento do risco de efeitos colaterais sobre o sistema cardiovascular, nomeadamente no risco de eventos aterotrombóticos. Torna-se por isso necessário conhecer e prevenir os efeitos adversos desses fármacos de modo a permitir a continuação da terapêutica antileucémica e minimizar a toxidade para os doentes. Este documento multidisciplinar, elaborado através de uma colaboração entre hematologistas e cardiologistas de vários serviços hospitalares portugueses, tem por objetivo rever a toxidade cardiovascular associada aos vários ITCs e estabelecer sugestões para o seguimento desses doentes. São ainda propostas medidas para a avaliação e redução do risco cardiovascular desses doentes, critérios de referenciação e discutidas interações medicamentosas relevantes.

The treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has significantly altered the prognosis of this disease, enabling five-year survival of over 90% with the latest-generation TKIs.1–3

The increased survival made possible by these new therapies, which now enable life expectancy close to that of the general population, has raised problems arising from the potential impact on long-term prognosis of the side effects of these new drugs, particularly on the cardiovascular system. Increases have been reported in cardiovascular events associated with TKIs, especially with second-generation agents.4 These side effects mainly consist of thrombotic arterial events, and so it is essential to assess cardiovascular risk factors and to apply cardiovascular prevention measures. However, analysis of cardiovascular complications associated with TKIs is hampered by the fact that CML mainly occurs in an age-group in whom cardiovascular disease and risk factors are already highly prevalent. Furthermore, most clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of these new drugs exclude subjects with known cardiovascular disease, meaning that the effects of TKIs on populations with existing disease are unknown. Finally, analysis of side effects has focused on metabolic abnormalities and major adverse events over a relatively short follow-up; there have so far been no prospective studies assessing the effects of TKIs on ventricular and vascular function.5

As well as the BCR-ABL protein that causes CML, TKIs also inhibit other kinases including PDGFR, c-Kit and Src that are also expressed in non-hematopoietic cells, and are thus responsible for non-hematological side effects.

Of the five TKIs currently available for the treatment of CML, imatinib was the first and for years was considered the standard of care. However, cases of resistance to or intolerance of imatinib led to the development of new TKIs, which are more potent inhibitors of BCR-ABL but have different toxicity profiles. The first of these second-generation agents were dasatinib and nilotinib, which have a stronger therapeutic effect than imatinib and are therefore now considered first-line treatment.6 The other TKIs are used less frequently: bosutinib is mainly prescribed as a third-line treatment, while ponatinib is indicated for specific BCR-ABL mutations.

The toxicity profiles of the three most used agents – imatinib, dasatinib and nilotinib – differ significantly. It is important to understand their effects, to identify patients at higher risk, and to undertake appropriate preventive and monitoring measures. Below we summarize the known manifestations of cardiovascular toxicity in these drugs.

Cardiovascular side effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitorsThe cardiovascular side effects of TKIs are not manifestations of a drug class effect but are in fact specific to each agent. Given the short time that some of the new TKIs have been available, it may be that only long-term use will enable a thorough assessment of all their side effects.

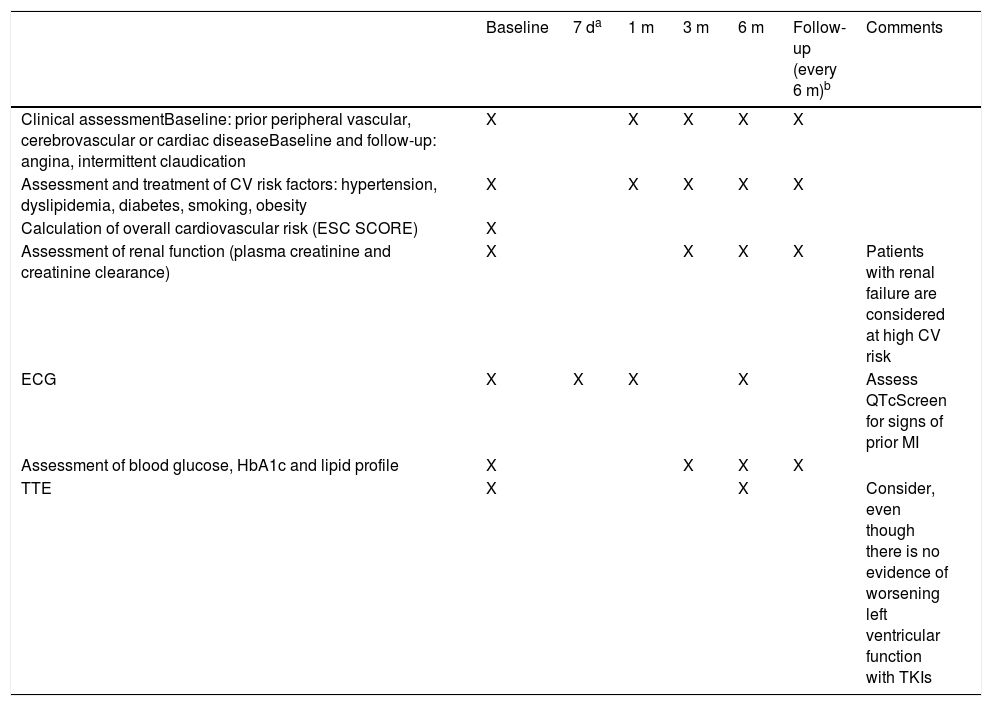

However, in general, TKI therapy may result in changes in the QT interval, as described below for each of the drugs in this class. It is recommended that the QT interval should be measured on the electrocardiogram (ECG) before beginning treatment with any TKI and should be monitored regularly thereafter. In the absence of more specific data, we suggest that an ECG be performed at three and at 12 months after beginning treatment (Table 1). In addition, patients should be screened for electrolytic abnormalities such as hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia, which may increase the risk for arrhythmias.

Recommendations for initial assessment and follow-up in patients undergoing tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

| Baseline | 7 da | 1 m | 3 m | 6 m | Follow-up (every 6 m)b | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical assessmentBaseline: prior peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular or cardiac diseaseBaseline and follow-up: angina, intermittent claudication | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Assessment and treatment of CV risk factors: hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Calculation of overall cardiovascular risk (ESC SCORE) | X | ||||||

| Assessment of renal function (plasma creatinine and creatinine clearance) | X | X | X | X | Patients with renal failure are considered at high CV risk | ||

| ECG | X | X | X | X | Assess QTcScreen for signs of prior MI | ||

| Assessment of blood glucose, HbA1c and lipid profile | X | X | X | X | |||

| TTE | X | X | Consider, even though there is no evidence of worsening left ventricular function with TKIs |

Heart failure was reported in initial non-controlled studies on imatinib. In an in-vitro study, imatinib affected the mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular ultrastructure, inducing apoptosis.7 Subsequent analyses of larger populations in multicenter studies found no increase in the incidence of heart failure above that expected for the age-group and associated comorbidities.5 In a review of 1276 patients receiving imatinib, most of those who developed heart failure had previous medical conditions predisposing to the disease.8 Another effect of imatinib is fluid retention, but this has little clinical repercussion and pleural effusion is very rare. Among the recommendations for patients treated with imatinib is cardiac monitoring in cardiology consultations in patients with prior heart disease.

DasatinibDasatinib is associated with pleural or pericardial effusion in 20% of patients.9,10 A different TKI should be considered in patients at risk of pleural effusion, especially those with a history of pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure. Pulmonary hypertension is another complication found with dasatinib, observed in 0.35% of cases,10,11 and so alternative TKIs should be used in patients with pre-existing pulmonary hypertension. In rare cases (<1%) QT interval prolongation may occur in patients treated with dasatinib.

NilotinibProlonged QT has also been described as being among the side effects of nilotinib.12 However, none of the published studies report prolongation of corrected QT interval (QTc) of >500 ms, which demonstrates that nilotinib is safe in this regard.13 As pointed out above, baseline and follow-up monitoring of the ECG is recommended; care should also be taken when administering antiarrhythmics or other agents that prolong QT, and hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia must be corrected.

One of the most discussed cardiovascular toxic effects of second-generation TKIs is the increase in thrombotic arterial events. An analysis of Swedish population-based registries revealed that CML itself increases the frequency of cardiovascular events.14 The second-generation TKIs, nilotinib and dasatinib, are also associated in clinical trials with a higher cardiovascular event rate than imatinib,4 as demonstrated in one study in which the incidence of thrombotic arterial events with dasatinib was 5% compared to 2% with imatinib and was 15.9% and 10% with doses of 400 mg and 300 mg of nilotinib, respectively, compared to 2.5% with imatinib. Such events are even more frequent with ponatinib,5 with their incidence reaching 17.5%. In this context, it should be pointed out that although second-generation TKIs are more often linked to thrombotic events in the above-cited trials, associated mortality was no higher in the second-generation arm of these trials than in the imatinib arm, while mortality caused by progression of CML was higher in patients receiving imatinib than in those receiving dasatinib or nilotinib, demonstrating the importance of effective antileukemic action in these patients. Large retrospective multicenter studies identified older age and metabolic disorders such as hypercholesterolemia or diabetes as major risk factors for the development of peripheral arterial disease.15 In an analysis that included data from the IRIS, TOPS, and ENESTnd trials, 92% of patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease had cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, older age and smoking.16 In the ENESTnd trial, there was at least one risk factor for atherosclerosis prior to therapy in 85% of patients with acute coronary syndrome, while another study revealed a significant association between ischemic accident and cholesterol levels and other cardiovascular risk factors.17

While the known metabolic effects of nilotinib, aggravated by the presence of hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia, may increase the frequency of cardiovascular events, it should be borne in mind that the population of patients with CML – whose mean age is 67 years – are already at significant risk of ischemic accidents, not only because of their age, but due to the accumulation of risk factors. There is accordingly debate whether such events are merely part of these patients’ natural history or are in fact secondary to nilotinib therapy.13 Furthermore, nilotinib may act in addition to established cardiovascular risk factors or other comorbidities by direct vascular effects, due to its interaction with discoidin domain receptor 1, or by metabolic effects on blood glucose and cholesterol levels, all of which contribute to occlusive atherosclerotic disease. It has also been suggested that pre-existing subclinical vascular disease before beginning therapy may be underestimated.

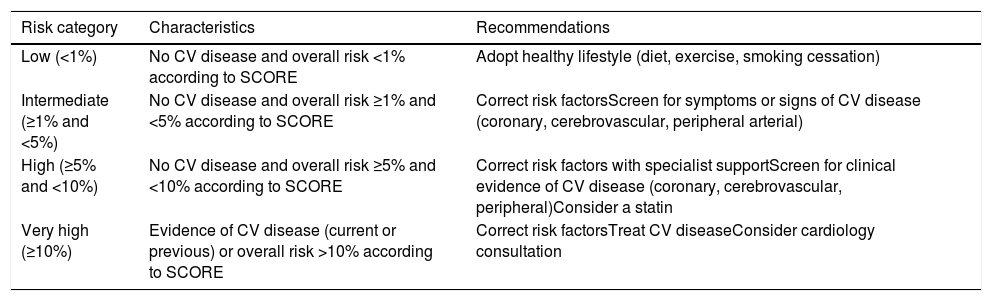

Breccia et al.18 recently performed a retrospective analysis of CML patients treated with nilotinib. Retrospectively applying the SCORE chart for cardiovascular risk estimation proposed by the European Society of Cardiology (the version for low-risk European countries including Portugal),19 they classified patients before beginning nilotinib and after follow-up as low (<1%), moderate (1-5%), high (5-10%) and very high (>10%) risk, on the basis of age, gender, cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, renal failure, obesity, and previous cardiovascular disease. The cumulative incidence of atherosclerotic events at 48 months was 8.5%. Higher risk categories were associated with a greater incidence of ischemic events, none of which occurred in the low-risk group. This study suggests that atherosclerotic risk factors must be detected early and throughout the treatment period in order to avoid ischemic events, and that the patient should be asked about symptoms of angina and intermittent claudication at every consultation.

The majority of studies on the effect of nilotinib (and also dasatinib and imatinib) on ventricular function excluded patients with previous ventricular dysfunction, while others did not systematically examine ventricular function by echocardiography. There is thus no information currently available to suggest that TKIs significantly affect ventricular systolic function as assessed by ejection fraction. One study found changes in diastolic function, implying that there may be more subtle changes in ventricular function.20 There is at the moment insufficient evidence to conclude that ventricular function is significantly affected, but this question should be explored in further studies, which should include more sensitive indicators of ventricular function.

BosutinibMost studies on bosutinib have shown no increase in the incidence of cardiovascular events.21,22 However, bosutinib inhibits signaling pathways that are also inhibited by ponatinib, such as the Src kinase family, and so until the etiopathogenic mechanisms of cardiovascular toxicity in TKIs are completely elucidated, patients taking bosutinib should be monitored for possible cardiovascular events.23 Likewise, most studies have not found that bosutinib prolongs QTc. In a study of 288 patients with CML, QTc prolongation was found in only two patients (>500 ms in one and >60 ms in the other),23 suggesting that the drug is safe but underlining the need for electrocardiographic assessment and monitoring.

PonatinibAlthough few studies on ponatinib have been published, it appears to be associated with a high risk for cardiovascular events, particularly arterial (occlusive arterial disease in 20% of cases) but also venous.24 In additions, hypertension is a frequently cited side effect of ponatinib and therefore measures must be taken to control blood pressure.25

Suggestions for assessment and monitoring of cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitorsOn the basis of currently available information, we propose an algorithm for assessment (Appendices 1 and 2) and monitoring (Tables 1–4) of patients with CML treated with TKIs.

Classification of overall cardiovascular risk and recommendations for each risk category.

| Risk category | Characteristics | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low (<1%) | No CV disease and overall risk <1% according to SCORE | Adopt healthy lifestyle (diet, exercise, smoking cessation) |

| Intermediate (≥1% and <5%) | No CV disease and overall risk ≥1% and <5% according to SCORE | Correct risk factorsScreen for symptoms or signs of CV disease (coronary, cerebrovascular, peripheral arterial) |

| High (≥5% and <10%) | No CV disease and overall risk ≥5% and <10% according to SCORE | Correct risk factors with specialist supportScreen for clinical evidence of CV disease (coronary, cerebrovascular, peripheral)Consider a statin |

| Very high (≥10%) | Evidence of CV disease (current or previous) or overall risk >10% according to SCORE | Correct risk factorsTreat CV diseaseConsider cardiology consultation |

Based on the SCORE charts of the European Society of Cardiology16 and the guidelines of the Portuguese Directorate-General of Health (Appendices 1 and 2).

Estimation of overall cardiovascular risk is based on risk of events in 10-year follow-up.

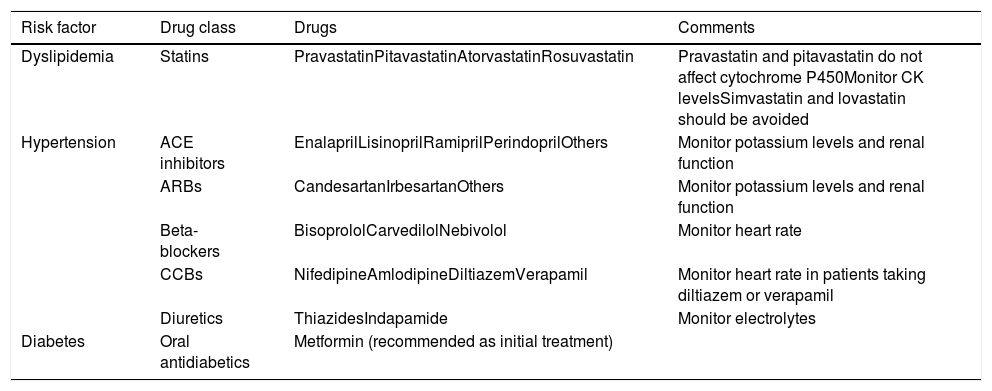

Drugs that can be used in association with tyrosine kinase inhibitors to control cardiovascular risk factors.

| Risk factor | Drug class | Drugs | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyslipidemia | Statins | PravastatinPitavastatinAtorvastatinRosuvastatin | Pravastatin and pitavastatin do not affect cytochrome P450Monitor CK levelsSimvastatin and lovastatin should be avoided |

| Hypertension | ACE inhibitors | EnalaprilLisinoprilRamiprilPerindoprilOthers | Monitor potassium levels and renal function |

| ARBs | CandesartanIrbesartanOthers | Monitor potassium levels and renal function | |

| Beta-blockers | BisoprololCarvedilolNebivolol | Monitor heart rate | |

| CCBs | NifedipineAmlodipineDiltiazemVerapamil | Monitor heart rate in patients taking diltiazem or verapamil | |

| Diuretics | ThiazidesIndapamide | Monitor electrolytes | |

| Diabetes | Oral antidiabetics | Metformin (recommended as initial treatment) |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; CCBs: calcium channel blockers; CK: creatine kinase.

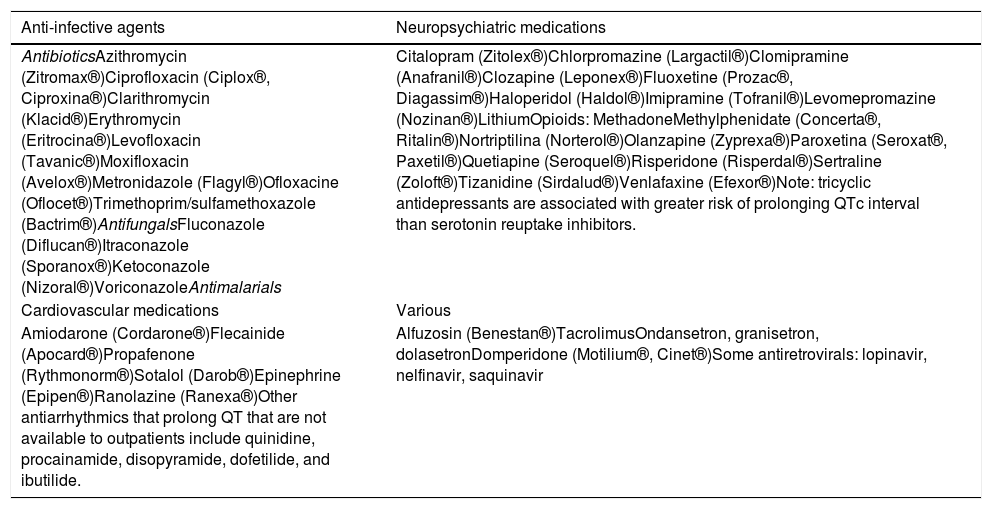

Drugs that prolong QT interval.

| Anti-infective agents | Neuropsychiatric medications |

|---|---|

| AntibioticsAzithromycin (Zitromax®)Ciprofloxacin (Ciplox®, Ciproxina®)Clarithromycin (Klacid®)Erythromycin (Eritrocina®)Levofloxacin (Tavanic®)Moxifloxacin (Avelox®)Metronidazole (Flagyl®)Ofloxacine (Oflocet®)Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim®)AntifungalsFluconazole (Diflucan®)Itraconazole (Sporanox®)Ketoconazole (Nizoral®)VoriconazoleAntimalarials | Citalopram (Zitolex®)Chlorpromazine (Largactil®)Clomipramine (Anafranil®)Clozapine (Leponex®)Fluoxetine (Prozac®, Diagassim®)Haloperidol (Haldol®)Imipramine (Tofranil®)Levomepromazine (Nozinan®)LithiumOpioids: MethadoneMethylphenidate (Concerta®, Ritalin®)Nortriptilina (Norterol®)Olanzapine (Zyprexa®)Paroxetina (Seroxat®, Paxetil®)Quetiapine (Seroquel®)Risperidone (Risperdal®)Sertraline (Zoloft®)Tizanidine (Sirdalud®)Venlafaxine (Efexor®)Note: tricyclic antidepressants are associated with greater risk of prolonging QTc interval than serotonin reuptake inhibitors. |

| Cardiovascular medications | Various |

| Amiodarone (Cordarone®)Flecainide (Apocard®)Propafenone (Rythmonorm®)Sotalol (Darob®)Epinephrine (Epipen®)Ranolazine (Ranexa®)Other antiarrhythmics that prolong QT that are not available to outpatients include quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide, dofetilide, and ibutilide. | Alfuzosin (Benestan®)TacrolimusOndansetron, granisetron, dolasetronDomperidone (Motilium®, Cinet®)Some antiretrovirals: lopinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir |

The drugs in this table may prolong QTc. Decisions whether to use such drugs should be based on a risk/benefit analysis. Alternative drugs should be used if possible, otherwise QTc should be monitored regularly. Based on Nielsen et al.26 and Li et al.27

Drugs are listed in alphabetical order within each category together with common brand names.

Irrespective of the patient's comorbidities, there are no absolute contraindications to any of the TKIs.

The aim should be to strike a balance between maximum efficacy and minimum toxicity. However, as the drug's antileukemic effectiveness is the main concern in advanced disease, this takes precedence over its toxicity profile.

For patients at very high cardiovascular risk recently diagnosed with chronic phase CML, imatinib and dasatinib are currently the preferred therapeutic options. Nilotinib is not recommended for these patients and is only indicated after careful assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, disease severity and the expected therapeutic benefit. In patients at low or moderate cardiovascular risk, any of the TKIs can be prescribed.

Ponatinib should not be prescribed for patients previously diagnosed with peripheral arterial disease, and nilotinib is not recommended in cases of known severe peripheral disease, although it may be considered if the disease is mild to moderate after assessment of risks and benefits.5

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Almeida AG, Almeida A, Melo T, Guerra L, Lopes L, Ribeiro P, et al. Novas perspetivas para a abordagem dos efeitos cardiovasculares dos inibidores da tirosinacinase em doentes com leucemia mieloide crónica. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:1–9.