Brugada syndrome, first described over 20 years ago, is characterized by a typical electrocardiographic pattern with coved-type ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads and a high risk of sudden death in otherwise healthy young adults.

The electrocardiographic pattern is sometimes intermittent, and fever is a possible trigger. The authors present the case of a 68-year-old woman who came to the emergency department with fever and syncope. A diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia was made. The electrocardiogram performed when the patient had fever revealed a type 1 Brugada pattern, which disappeared after the fever subsided. After other causes of Brugada-like pattern were excluded, Brugada syndrome was diagnosed and a cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted.

This case demonstrates that this entity can be diagnosed at more advanced ages and highlights the usefulness of electrocardiography in a febrile state.

A síndrome de Brugada, descrita há cerca de 20 anos, caracteriza-se eletrocardiograficamente por uma elevação convexa do segmento-ST nas derivações precordiais direitas e pelo elevado risco de morte súbita em jovens aparentemente saudáveis.

Este padrão eletrocardiográfico é, por vezes, intermitente, sendo a febre um possível fator precipitante. Os autores apresentam o caso clínico de uma doente de 68 anos que recorre ao serviço de urgência por febre e síncope. Feito o diagnóstico de pneumonia adquirida na comunidade. O eletrocardiograma realizado em contexto de febre revelou um padrão de Brugada tipo 1, que desapareceu após resolução do quadro febril. Excluídas outras causas de padrão Brugada-like foi confirmado o diagnóstico de síndrome de Brugada e realizada implantação de cardioversor-desfibrilhador.

Este caso ilustra a possibilidade do diagnóstico desta entidade poder ser feito numa faixa etária já avançada e reforça a utilidade da realização de um eletrocardiograma em contexto febril.

Brugada syndrome (BrS), first described as a clinical entity in 1992,1 is an autosomal dominant disease associated with a high risk of sudden cardiac death in otherwise healthy young adults.2

BrS is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 5/10000, and affects both sexes but is eight times more common in males.2 It is characterized by a typical electrocardiographic pattern with coved-type ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1–V3).2 Although this pattern is characteristic, it is sometimes intermittent, which can hinder diagnosis. Fever is a known triggering factor.3

The authors present the case of a patient diagnosed with BrS during a febrile state.

Case reportA 68-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia and smoking was medicated as an outpatient with amlodipine, indapamide and rosuvastatin. She came to the emergency department with fever of one day's duration, pleuritic-type pain in the anterior right hemithorax radiating to the back, non-productive cough and an episode of loss of consciousness without prodrome, of short duration and with spontaneous recovery, and no postcritical period. The patient had no history of previous syncope or nocturnal agonal respiration or family history of sudden death.

On admission she was subfebrile (37.4°C) and hemodynamically stable (blood pressure 130/65 mmHg and heart rate 88 bpm). Physical examination revealed no abnormalities on cardiac or pulmonary auscultation and there were no indirect signs of deep vein thrombosis.

Laboratory tests showed elevated inflammatory parameters (leukocytes 16800×103/μl and C-reactive protein 19.6 mg/dl) but no elevation of D-dimers or troponin I. The chest X-ray revealed a round alveolar opacity in the lower half of the right pulmonary field.

In view of her symptoms and the laboratory and imaging findings, empirical antibiotic therapy was begun for community-acquired pneumonia (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and azithromycin).

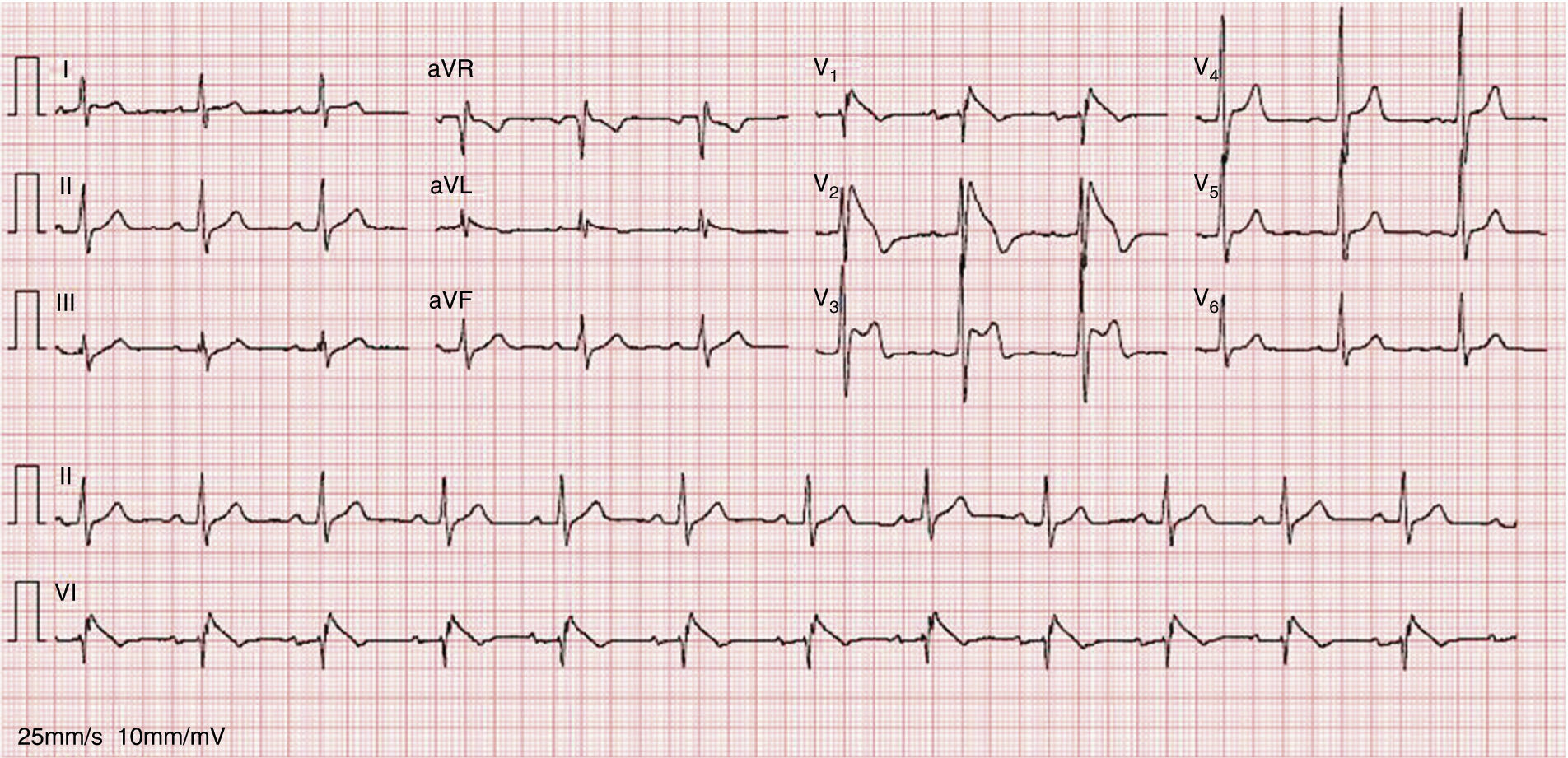

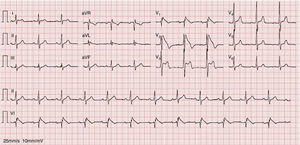

An electrocardiogram (ECG) performed to investigate the episode of loss of consciousness revealed first-degree atrioventricular block, incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST-segment elevation, down-sloping in V1 and V2 and horizontal in V3, together with T-wave inversion (Figure 1).

A diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome was excluded, despite the existence of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, since the patient presented with non-typical chest pain and no elevation in myocardial necrosis markers was seen in serial assessments. The possibility of pulmonary embolism suggested by the patient's symptoms was ruled out by normal D-dimer levels.

A diagnosis of BrS (fever-induced type 1 electrocardiographic pattern and syncope) was assumed and the patient was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) for monitoring of arrhythmias.

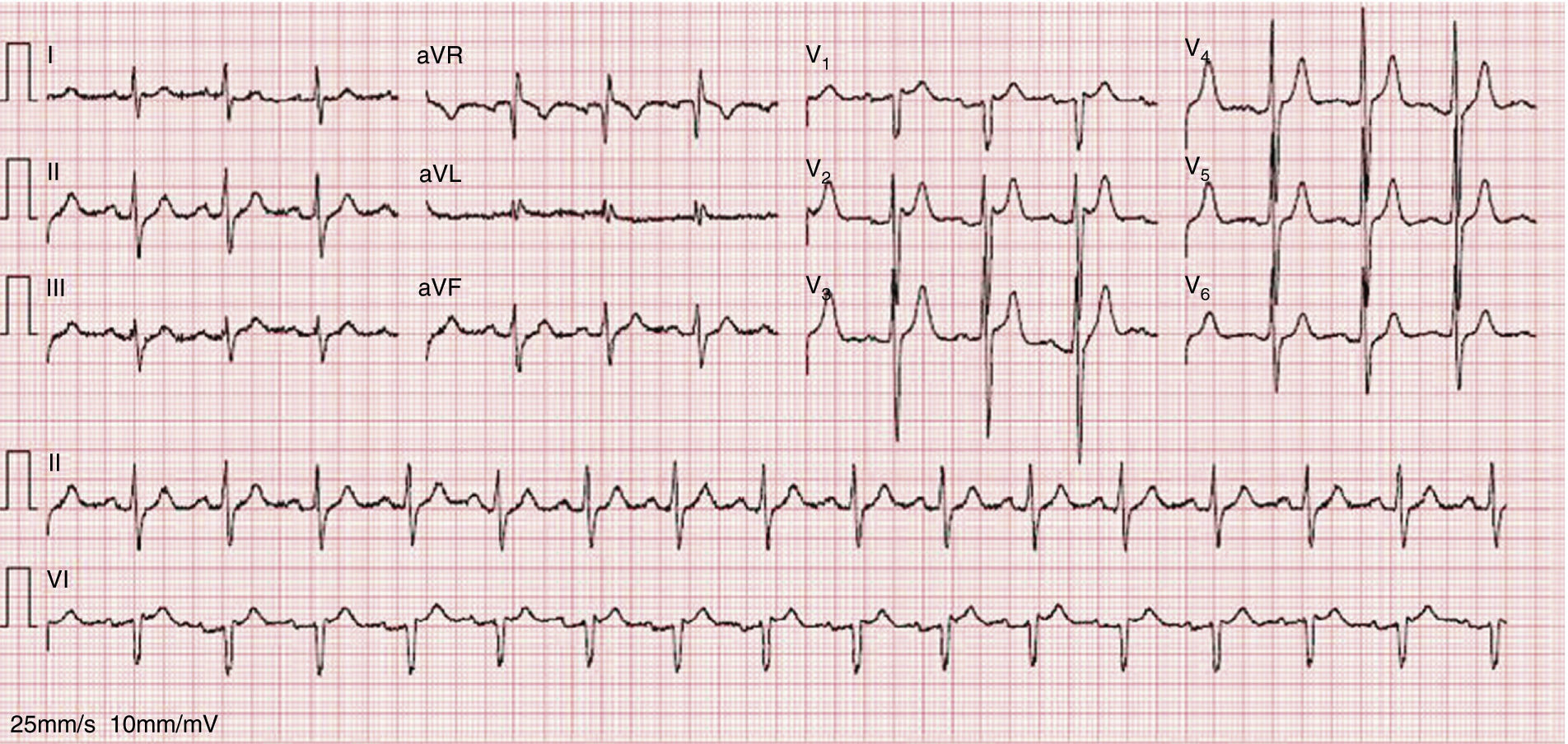

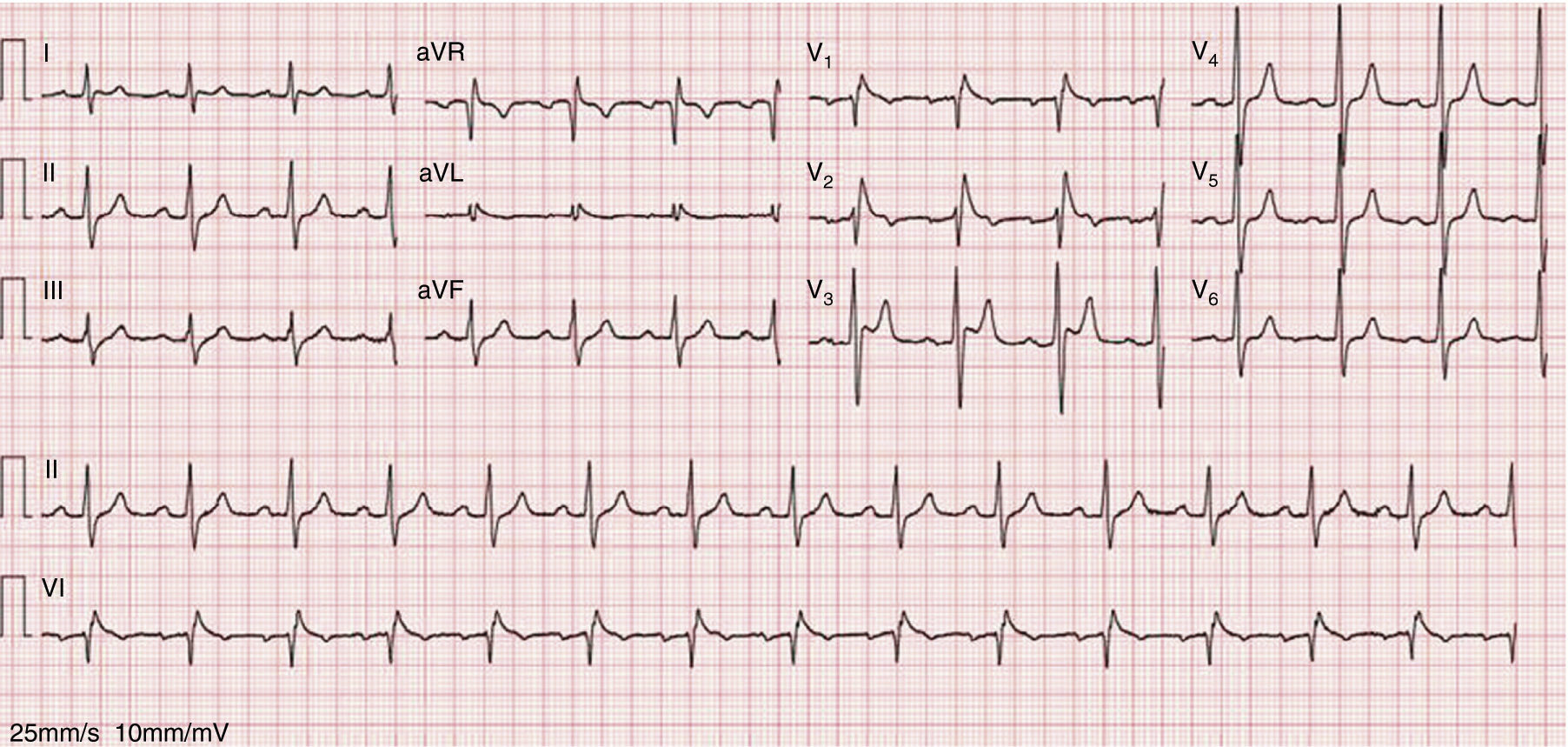

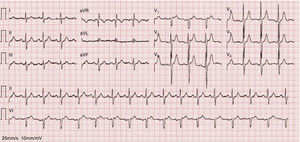

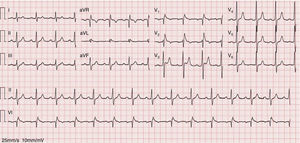

As the infection resolved, the ECG evolved to a type 3 Brugada pattern (Figure 2). However, an ECG with leads V1 and V2 placed in the third intercostal space continued to show a type 1 Brugada pattern (Figure 3).

There were no arrhythmic events during the patient's stay in the CICU.

Transthoracic echocardiography ruled out structural or functional heart disease. In the light of a definitive diagnosis of BrS in a patient with syncope, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted, in accordance with the European Society of Cardiology guidelines (class IIa recommendation).4

The patient was referred for genetic study but no mutation was found. She has two children, who are asymptomatic and have normal ECG.

At 36-month ICD follow-up no arrhythmic events had been detected.

DiscussionBrS is a hereditary channelopathy with autosomal dominant transmission and incomplete penetrance (approximately 16%, but this figure varies in different families).5 It is a relatively common cause of sudden cardiac death (4% of all sudden deaths) and is responsible for up to 20% of sudden deaths in patients without structural heart disease.6 The clinical phenotype is eight times more common in men than in women.7 The first arrhythmic event occurs at a mean age of 40.7

The case presented here is somewhat atypical, since the first clinical manifestation (syncope) occurred in a female patient in her late 60s.

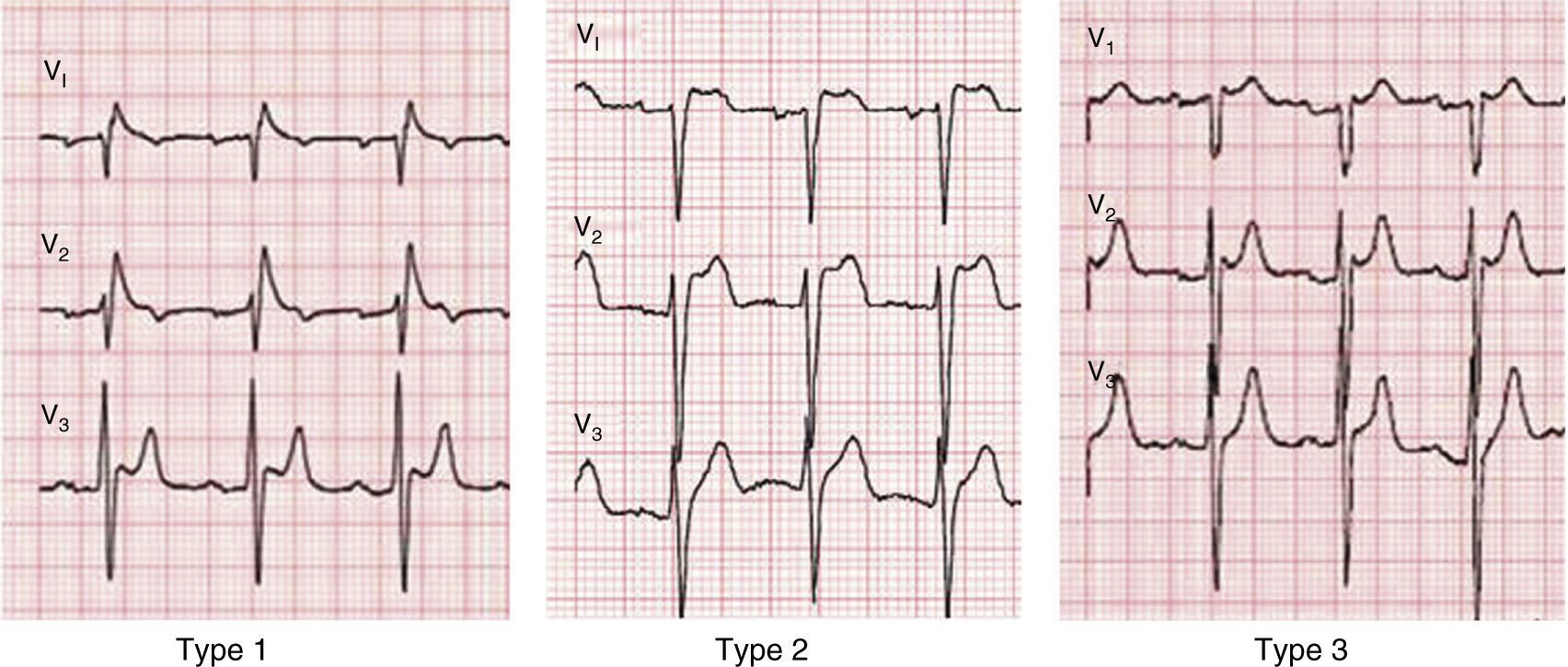

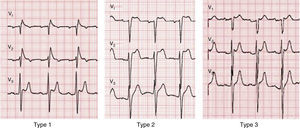

A diagnosis of BrS requires the presence of a characteristic electrocardiographic pattern: coved-type ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm followed by a negative T wave in >1 right precordial lead (type 1).2 Type 2 (saddleback appearance ST-segment elevation with a high takeoff ST-segment elevation of ≥2 mm, a trough displaying ≥1 mm ST elevation, and then either a positive or biphasic T wave) or type 3 (either a saddleback or coved appearance with an ST-segment elevation of ≥2 mm in the initial portion and <1 mm in the final part) is diagnosed when the type 1 pattern is induced by provocation with ajmaline or flecainide (Figure 4).2 This classification of BrS electrocardiographic patterns into three types has been criticized, and a division into type 1 and type 2 is currently recommended, the latter encompassing the previous types 2 and 3.8

Besides a type 1 electrocardiographic pattern (spontaneous or induced), a diagnosis of BrS also requires one of the following: documented ventricular fibrillation (VF) or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT), a family history of sudden cardiac death at age <45 years, coved-type ECGs in family members, inducibility of VT with programmed electrical stimulation, syncope, or nocturnal agonal respiration.2

The type 1 pattern is sometimes intermittent, which can hinder diagnosis. However, it can be triggered by various factors, including fever, certain drugs and ionic imbalance, which interfere with the dynamics of cardiac sodium channels.9 In 51% of BrS patients the ECG fluctuates between diagnostic and non-diagnostic patterns.10 Provocation testing with ajmaline or flecainide can reveal a type 1 ECG pattern when the diagnosis is suspected.11 Among patients with a negative flecainide provocation test, 32% test positive with ajmaline, and so the latter is to be preferred.11

This intermittent character was observed in our patient, who initially presented a typical pattern during an episode of fever, but when the infection and fever subsided this changed to a type 3 pattern. However, an ECG with leads V1 and V2 placed in the third intercostal space revealed a type 1 pattern, which demonstrates the value of this technique in patients with a high suspicion of BrS, since it increases diagnostic sensitivity from 15% to 52%.2,7,12 Fever is known not only to unmask a type 1 pattern but also to trigger episodes of VT and VF.13 Reports in the literature suggest that type 1 Brugada may be up to 20 times more common in patients with fever.14 In a large series of BrS patients, fever was the triggering factor for ventricular arrhythmias in 18% of cases.15 It has also been reported that fever can unmask a type 1 pattern in patients with a negative flecainide test,16 although it is not known whether this is also true of cases with a negative ajmaline test. It is therefore suggested that all patients with suspected BrS should undergo an ECG during a febrile episode, whatever their response to drug provocation testing.16

In BrS there is an imbalance in ion currents at the end of phase 1 of the action potential favoring repolarization due to reduced activity of sodium channels (INa), resulting in increased activity of repolarization currents (potassium channels, Ito) with no or reduced opposition from depolarizing currents. These alterations are more marked in areas with greater density of Ito channels such as the right ventricular epicardium, leading to transmural dispersion of action potentials, with some areas where there is loss of the action potential dome and others where the action potential is normal. There is thus a vulnerable period during which the action potential can propagate from areas with normal repolarization to areas of early repolarization, creating the substrate for re-excitation by phase 2 reentry. This leads to the development of ventricular extrasystoles which create a circus movement reentry and hence VT or VF.9,17,18

Keller et al. demonstrated that mutated sodium channels show a severe or total loss of function at physiological temperatures, and so this loss of function is unlikely to increase during fever.3 Non-mutated (wild-type) sodium channels are also sensitive to temperature changes, higher temperatures reducing their activity. Thus, in heterozygous individuals, increased inactivation of wild-type sodium channels leads to fever-induced arrhythmias, and in genetically susceptible individuals this small additional loss of sodium channel function upsets the delicate balance between the INa and Ito currents, resulting in transmural heterogeneity of action potentials due to early repolarization in areas with a greater concentration of Ito channels, which reduces opposition to sodium currents. This establishes a substrate for phase 2 reentry, which can result in VT/VF.3,14,19,20 It is also plausible that temperature-dependent alterations may affect other ion currents, possibly strengthening the Ito current, which would trigger early repolarization in epicardial tissue, where these channels are denser.17

Risk stratification in BrS patients is controversial, but in our patient the decision to implant an ICD was straightforward, since she had spontaneous type 1 pattern and had suffered syncope. Implantation of an ICD is a class I recommendation in individuals with type 1 Brugada pattern and a previous episode of aborted sudden death and a class IIa recommendation in patients with history of syncope, since these patients are at proven high risk for recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias (17–62% at 48–84 months of follow-up).21–23

Management of asymptomatic patients is the most controversial aspect of risk stratification in BrS.24 The incidence of malignant arrhythmias in these individuals ranges between 0.24%/year and 1.7%/year in different series.25 It is thus important to find risk variables that will identify patients who will benefit from ICD implantation for primary prevention.

The presence of a spontaneous type 1 pattern, irrespective of the placement of leads V1–V3,12 and male gender, are associated with worse prognosis.26

Programmed electrical stimulation (PES) to induce ventricular arrhythmias is the most controversial risk stratification method. According to various publications by the Brugada brothers, induction of arrhythmias by PES is an independent predictor of malignant arrhythmic events,26 and Giustetto et al. demonstrated its high negative predictive value.27 However, the findings are inconsistent and other studies failed to confirm an association between a positive result on PES and the occurrence of arrhythmic events22,23,28,29 or its negative predictive value.29 These discrepancies may be explained by differences in stimulation protocols.24

Other risk markers have been proposed, including QRS fragmentation,29 ventricular refractory period <200 ms29 and augmented ST-segment elevation during recovery from exercise.30 Atrial fibrillation, found in 10–54% of BrS patients, has also been associated with worse prognosis.31

By contrast, none of the known SCN5A mutations is linked to worse outcome, or to a family history of sudden death.7,11

Despite advances in characterization of BrS in recent years, ICD implantation is the only effective treatment to prevent sudden death and is a generally accepted option for symptomatic individuals.2

In countries where the cost of ICD implantation is prohibitive, in children, in patients who receive multiple appropriate ICD shocks, and in cases of arrhythmic storm, drug therapy has an important role.24 The aim is to rebalance the ion currents by blocking Ito channels (quinidine and tedisamil), boosting the L-type calcium current (isoprenaline), or both (phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitors such as cilostazol).2 These agents are effective in normalizing ST-segment elevation and controlling arrhythmic storm, especially in children.32

Investigation of the family after identification of an index case is essential in view of the condition's autosomal dominant transmission. Genetic study is of limited value, since a pathogenic SCN5A mutation is found in only 18–30% of cases, and even in these penetrance is at most 16%.5,9 Nevertheless, when there is a known mutation, carriers can be identified as being at risk of developing the disease.25

Both the children of the patient presented are asymptomatic and have normal ECG irrespective of the placement of leads V1–V3. According to some authors they should be referred for provocation testing,6 but a negative result would not exclude the diagnosis,16 and so it is important to follow such individuals and to perform regular ECGs, particularly during febrile states. In fact, an ECG in any patient with a history of syncope during fever would appear to be a good way to increase diagnostic sensitivity. Fever is also known to trigger arrhythmic events in BrS patients.13

It is essential to treat the fever immediately, as well as to be aware of which drugs increase arrhythmic risk. Consultation of the list at www.brugadadrugs.org is advised before starting any drug in a BrS patient.33 In the case reported, we were confident that the antipyretic and antibiotics prescribed were safe, since no arrhythmic events have been associated with them.

ConclusionsBrS is notoriously difficult to diagnose and to perform risk stratification, as exemplified by the case presented. The intermittent nature of the type 1 pattern can delay diagnosis, and so, in the authors’ opinion, all patients with fever and a history of syncope should undergo an ECG, which may turn out to be a cost-effective measure.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

FinancingRui Providência received a research grant from Medtronic and an electrophysiology training grant from Boston Scientific and Sorin.

Conflicts of interestRui Providência received a research grant from Medtronic and an electrophysiology training grant from Boston Scientific and Sorin. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Madeira M, Caetano F, Providência R, et al. Padrão de Brugada tipo 1 induzido pela febre. Rev Port Cardiol. 2015;34:287.